Last updated: April 9, 2024

Article

Podcast 151: Water Conservation and Use in the Western United States

The Importance of Water in the Western United States

Catherine Cooper: Hello, my name is Catherine Cooper. I am here with ...

Bob Crifasi: Bob Crifasi.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today.

Bob Crifasi: Yes, thanks for having me.

Catherine Cooper: What first interested you about water in the West?

Bob Crifasi: I've always been interested in doing things like backpacking and rafting and canoeing. Ever since I started visiting various desert canyons many years ago, I just became fascinated by it. I also have undergraduate degrees in geology and chemistry and masters degrees in geology and environmental science.One of the things as part of all of that is I became really interested in geomorphology, and really geology is what brought me out to the West so that I could learn about and see things. I went to school at University of Colorado in Boulder and Denver and started traveling all across the region and became very interested in rivers, geomorphology, everything that's associated with that. And the more I learned, the more interested in all of the different arcane aspects of water I became.

Catherine Cooper: In the Western United States water is so crucially important. Could you describe that importance to the various cultures in the West and how people approach water differently?

Bob Crifasi: Bob Crifasi.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today.

Bob Crifasi: Yes, thanks for having me.

Catherine Cooper: What first interested you about water in the West?

Bob Crifasi: I've always been interested in doing things like backpacking and rafting and canoeing. Ever since I started visiting various desert canyons many years ago, I just became fascinated by it. I also have undergraduate degrees in geology and chemistry and masters degrees in geology and environmental science.One of the things as part of all of that is I became really interested in geomorphology, and really geology is what brought me out to the West so that I could learn about and see things. I went to school at University of Colorado in Boulder and Denver and started traveling all across the region and became very interested in rivers, geomorphology, everything that's associated with that. And the more I learned, the more interested in all of the different arcane aspects of water I became.

Catherine Cooper: In the Western United States water is so crucially important. Could you describe that importance to the various cultures in the West and how people approach water differently?

Image courtesy of Bob Crifasi

In the Eastern states, wetter regions, there's ample rainfall, there's rivers, there's lakes that provide relatively easy access to water. Once we past what's roughly the hundredth meridian, so Central Kansas and going West, the amount of natural rainfall drops pretty substantially, and in certain regions it's very low.

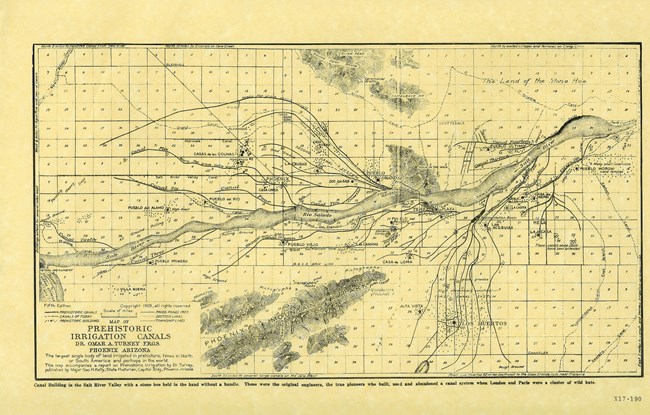

Without having supplemental water or adding water to irrigate and grow crops, you just don't have a society or have any ability to have a viable culture. You really need to have water. The Native Americans are really the original savants with using water in the West. They had so many remarkable adaptations to live in this area.In the rainier areas where there were rivers, they built diversions. They started to build reservoirs, check dams. They had remarkable innovations for utilizing the entire landscape for accessing and manipulating water. They would carefully look at the landscape to see which plants should be planted where on the hillsides and in the valley bottoms to take the best advantage of the moisture. And so they were really were some of the original people, with well over 10,000 years of experience, changing and manipulating water.

Not only that, but they adapted their plants, corn, and other crops to the water resources that were available to them. They were really integral in paving the way for anyone who came later as to how you use the water. The Spanish came in first in Mexico with Cortes, but then they had the Coronado expedition that came up for conquest in 1540s. And then the Spaniards settled.They brought some irrigation technologies from the Iberian Peninsula, and they started to build ditches that they called acequias. The word acequia itself comes from the Arabic al-sakiya, which means water conveyance. And so they had learned from the Moors of North Africa, also desert people, how to manage water in dry regions.

Once the Spaniards were in New Mexico, they watched how the indigenous people were using their water, and their water systems merged in many ways with the pre-existing Indian cultures. They appropriated and took for themselves the Indian ditches and then transformed them. They used some of the processes of cooperation that they saw the Indians doing, and they adopted many things that they saw from the Indigenous people to build their own systems.

Today, across the West we have, at least in the Southwest, in New Mexico, parts of Arizona, Southern California, even in parts of Texas, a long legacy of these acequia cultures. They really are integral, particularly for small communities and how they use water.

Now, the Euro-Americans came in with the Mexican-American War in the 1840s. And when they came in, they saw how the Indians and the Hispanic people were using their water resources. That informed what the 49ers were doing when they went to California in the gold rush. It informed how the Mormons built their irrigation works up in the Salt Lake area, and how the gold miners and new farmers that were coming into Colorado's Front Range built their systems. It was all a process of building one on top of the other and learning from the previous occupants how to live in this arid environment.

Technologies for Conserving Water

Image courtesy of Bob Crifasi

Bob Crifasi: They like to say the present is the key to the past. I like to invert that in some ways and say the past is the key to the present. If we look to the past and see how our predecessors did things, we find that they were actually very logical people and that a lot of what they did were based on rational decision-making and how to live in the environment. They would see how the rivers flowed on the landscape. They would look at the geomorphology where the terraces were. They would see how the riparian landscape sat in there, and then they manipulated that to survive.

As each generation has come in, we've built on that. What we have today is a very layered landscape with the older water facilities having influenced what comes next. For example, when the first white settlers came into the Front Range, they were very practical. They weren't going to do any more work than they needed to, and so they built their irrigation ditches in the valley bottoms. As more people came in, the land was taken, and then the next settlers asked, well, how are we going to get water? And they started to build these ditches that would go up onto the terraces.

Then later people would realize, well, the water's polluted because of mining, so let's build a pipeline from the mountains, and so on. And so they systematically built up higher onto the terraces. They moved higher into the canyons. As each generation came in, they layered their new uses on top of pre-existing uses. And so it became pretty convoluted, but really it was all based on a series of rational decisions at each stage of the development process.

Current Conservation Challenges

Image Courtesy of Bob Crifasi

Bob Crifasi: That's kind of the million-dollar question in many ways. Water is an existential question in the West. We're starting to bump up against natural limitations in a way that we haven't previously. We've fully appropriated the rivers and lakes in the West. We've built reservoirs for 150 years, and with climate change, that's kind of dialing back the availability of water in a way that we have never seen before.

What we're grappling with is, I think, not how do we develop new water resources, but how do we reallocate the water resources we already have and to utilize what we've already developed in a more efficient and pragmatic manner. We're dealing with scarcity in a way that we haven't in the past. In the early 20th century, water conservation meant building large dams. Hoover Dam was constructed as a conservation project. The people of that era saw conservation as putting water in a reservoir so that it wouldn't run downhill and out of their state.

Now conservation is seeing how do we maximize soil moisture? How do we create intricate ways of reusing water? How can we take water that has been maybe flushed down the toilet, cleaning it up and using it for irrigation, or in some instances even in homes. So the ideas of how we utilize water has become more sophisticated and is in response to the scarcity that we're now experiencing.

Always More to Learn about Water

Photo by John Chacon / California Department of Water Resources, (public domain). Image Courtesy of Bob Crifasi

Bob Crifasi: Oh, my. Yes. When I did it, there were two categories of subjects that I wanted to deal with and incorporate. There were some that I was like, this is really cool. I should include it. But when I sat down and actually wrote the book, it was like, well, it's going to just expand the book size beyond any reasonable means, and my publisher will just say, oh, my goodness. We can't do this. There were a few of those, and I won't get into those, but they are out there.

There were two or three big things that I had tried to find information about. I would love to see a PhD thesis here or there dealing with some of these things. For example, I'll back up a little bit. One of the things I really tried to address in the Western Water, A to Z was Indigenous use of water and to give them a meaningful voice that other books of water maybe had not done previously. There's a lot of really good books on water, but it tends to start with the end of the Civil War and the beginning of the Euro-American era.

I really wanted to give a voice to and a shout-out to the Indigenous and Hispanic cultures that did so much to lay the groundwork. Extending on that, I would really love to see some deep work on gender. You start going through the work on Western water, particularly Euro-American, and it tends to be white males, and it wasn't just all white males. The history is rich and varied, and I'd really like to see more with gender.

I also think a very important piece is environmental justice. The misallocation of water in the West tends to follow economic and racially discriminated communities. If you are a wealthy community, you're going to have very good water and wastewater infrastructure. If you are poor communities, you're going to be facing more issues around pollution, access to water, and things like that. I think social justice is another aspect.

And then there's another piece that I had just found nothing meaningful, at least for me, it's probably out there, I didn't find it, regarding African-Americans and their use of the water in the West. There were certain communities that, agricultural communities, for example, I can think of Deerfield in Eastern Colorado was an agricultural community, but there really isn't a lot around that subject as well. And I think it would be really fascinating to see how those communities dealt with water issues and bring some of that into the story to round out the picture so that it's more inclusive for every community that we have.

Catherine Cooper: That's a great note to end on. For anyone listening, you just have three thesis topics you can go dive into.

Bob Crifasi: I would love to see that. If you want somebody to read the thesis when it's done, I'd love that, too.Catherine Cooper:Thank you so much for joining us today.Bob Crifasi:Yeah, thanks. It's my pleasure. It's really fun to talk to you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.