Last updated: January 29, 2024

Article

Podcast 147: Communities of Ludlow

Learning about Ludlow

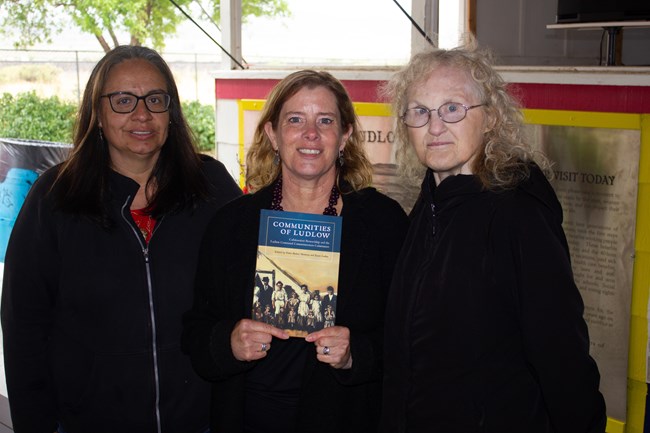

Photo courtesy of Karin Larkin

Karin Larkin: Karin Larkin.

Fawn-Amber Montoya: I'm Fawn-Amber Montoya.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you both so much for joining me today. You both recently published a book called “Communities of Ludlow: Collaborative Stewardship and the Ludlow Centennial Commemoration Commission.” Could you give a brief summary of the events?

Karin Larkin: The Ludlow Massacre was the culmination of one of the most violent events in US labor history, but very few people know about it. It happened over a century ago in 1913 and 1914 when southern Colorado coal miners went on strike to fight for better living conditions, safer working conditions, and fair wages. Thousands of miners and their families went on strike in September of 1913. They were kicked out of their company owned housing, so they moved into tent colonies that were set up in advance for them up and down the strike zone. So, they lived in these tent colonies for 14, 15 months. They suffered through one of the coldest and snowiest winters on record. Tensions ran pretty high between the strikers and the company, the militia, the Colorado National Guard who were policing the strike. Ludlow was the largest of these tent colonies. And on April the 20th, 1914, bullets flew through the Ludlow tent colony.

To escape the violence, four women and 11 children went and hid in a cellar that they had dug out underneath one of their tents. When the gunfire ceased, the militia and the National Guard came through, and they lit the tent colony on fire. And all but two women who escaped, the other two women and 11 children were all suffocated and died in that cellar that day. This sort of horrific event was a wake-up call for the nation, not just about the conditions and the coal mines, but the conditions and what was happening during the strikes, which was generally ignored. And this led to a lot of reforms, congressional inquiry, and changes in the labor laws throughout the country, and it's given us some of the privileges that we enjoy today.

Catherine Cooper: Could you talk about how each of you became aware of the Ludlow Massacre and became involved in the study and sharing of this history?

Fawn-Amber Montoya: My family is actually from southern Colorado. They migrated north from northern New Mexico in the late 1800s and settled in a small town outside of Trinidad, Colorado. It was known as Camp Engle or Engleville. When I was growing up, we lived outside of Trinidad in a small town called Hoehne, Colorado, and it was my first field trip for third grade. We went to the tent colony site. In, I think it was 2005, I was doing research for my dissertation, and I had driven by the site a number of times, been at the site a number of times, but my great uncle, we were getting ready for a family reunion. My great uncle was nowhere to be found because he had gone to Ludlow. And I remember that really sticking in my head about how important it was for my uncle as a former coal miner and to be from Trinidad, to be present at Ludlow on the morning of the family reunion. That Ludlow was as important to him as it was to his family. And so that was just something that had stuck with me for a very long time.Then when I was doing research on my dissertation, I was planning to look at Southern Colorado and the steel mill during World War II. And so, I was driving from Texas Tech University to the Steelworks Museum of the American West to do my research, and I would drive by Ludlow every time.

And I reached a point where I had to figure out that Ludlow wasn't done yet. I think sometimes there's been some really amazing books that have been written on Ludlow, “Killing for Coal,” specifically by Thomas Andrews. And so you can get the feel of the work's been done. What I started writing on was the community of Ludlow and the memory of the Ludlow Massacre. And that was a place where I found for my own scholarship, the work hadn't been done or needed to continue to be worked on. And I think Karin and I have addressed this in this book, that there's still more to be researched about the Ludlow Massacre. We in no way see this as the final say or the final piece. So, we would always encourage scholars to continue to embrace this work, but to make sure that they're very thoughtful about the communities of Ludlow and the rich histories and relationships that have been developed and to try to continue to honor those memories.

Courtesy of the Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project.

But we were also finding children's toys and parts of baby bottles, heirloom dishes and canning jars that still had food in them. And it just really personalized this history for me in a way that it was a touching reminder. So that gave me this direct and tangible connection to the Ludlow history, but also the massacre that really touched me.

Including Multiple Voices in History

Courtesy of the Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project.

Fawn-Amber Montoya: I would probably say I don't think that we started off with the intentionality of this multi-vocality. The book in many ways was “What were the next steps?” And after the end, the sundown of the official commission and the writing of the governor's report, I think that we knew we didn't want it to just sit on a table or sit on a bookshelf. We wanted the story and that experience that we had of connecting with community and these voices to become the history. One of the difficulties of being scholars and for myself of being a historian, it's about who gets to tell a story and what becomes the official histories. And we knew that unless we recorded this in a way where it would become part of the history that what we had done could be lost. And not just what we had done, but all of the contributions and these stories that were uncovered or brought to the forefront would be lost.I think in many ways the book reflects the variety of people who we were able to engage with in the commemorations, both either as audiences or as presenters, as community members who were present in these spaces who sometimes just provided the buildings for us to meet in.

One story that it is not included in the book is Carolyn Newman, who is a Mother Jones re-enactor, who runs a museum in Walsenburg Colorado. And she did a series of newspaper articles where she had looked back at the newspapers from 1913, 1914 and put them back into the newspaper 100 years later.And so, if I could go back and say whose story should be included, I would've probably figured out a way to make sure I wrote Carolyn into that. But I think it was also that this wasn't about us trying to control the narrative. We wanted to very much be reflective of how each of these individuals were or are. And so, I think, like I said, I don't think it was always us thinking, oh, we have to do it in this way. It was as we started to put together the book that this is what the commission really felt like on a regular basis.

Karin Larkin: One of the biggest challenges for academics is first of all, recognizing the sort of bias and the gaps in the documentary and the historical record, and then how can we ethically as well as accurately complete or fill in those gaps. And so, figuring out ways to make sure that we can include diverse stories, but also make sure that the stories that we're including add value to the historic record, as well as balancing this desire as an academic to make sure that the information is authentic, and it's accurate, there are multiple lines of evidence to help support it. Sometimes you don't have multiple lines of evidence to support some of the facts of history. One of the challenges is figuring out ways to be open-minded and open to different perspectives. And then how do we include those in ways that other academics will recognize their validity, right?

And so that's one of the things that we were very intentional in including Linda Linville's story within a published academic book because her family story had been not just excluded, but was discounted by historians in the past. And we felt that there is value in adding the lineal descendants’ stories in an official telling of the story because they had been intentionally excluded for so long. I think one of the challenges is balancing these ethical dilemmas with academic rigor. And that's something that I struggle with in my own scholarship, but I don't think necessarily it's something that a lot of historians, academics spend enough time thinking about and grappling with these issues.

Who Do We Write For?

Photo by Karin Larkin.

And when Karin and I had the opportunity this past summer, because annually there is a Ludlow Massacre Memorial, and Karin and I were able to be there, and we were able to give Mary Petrucci, who is the granddaughter of the first Mary Petrucci, a copy of the book. And to be able to show her the picture of her father in the book, and that her father, whose brother and sisters died at Ludlow and whose mother had to live the rest of her life knowing that her children had died. That is who our audience is. We wrote the book for people like Mary.

We've spent a lot of time with this and in a lot of different ways, whether it was through our own personal research, background readings, other people speaking about it, being present on site. I'm always amazed at the moment when people get it, when for them they have that moment of, oh my gosh, this is the story. This is the craziest, most horrific, painful story that they've ever heard. And I think for me, I come back to that again and again, is that these women that died and these children that died, and the survivors and the descendants that this scarred them. It killed them, it scarred them. It scarred the land. This trauma that was inflicted continued to live on, and it left a legacy. And that in the commission's work, we didn't undo what had been done.

That trauma is still there. It's still there present in the lives of the people. That trauma is still very present at the site. You have moments when you can still feel it. And that violence that was left on the land left a mark. And I think that's what I come back to again and again. I still come back to, I don't live in Colorado now, but I still come back to Ludlow annually. And I think that's no matter what we did, we could erase the horror that had occurred. I think we've done our best to bring justice to the people in the ways that we could. And I think the story has to be continued to be told over and over again. And no matter how many times I hear about Linda or how many times I hear about Mary, or how many times I hear Mary Petrucci and what had happened to her, how many times I teach this or talk about it, or in different places that I hear the story, it doesn't soften. And it's still very painful for me.

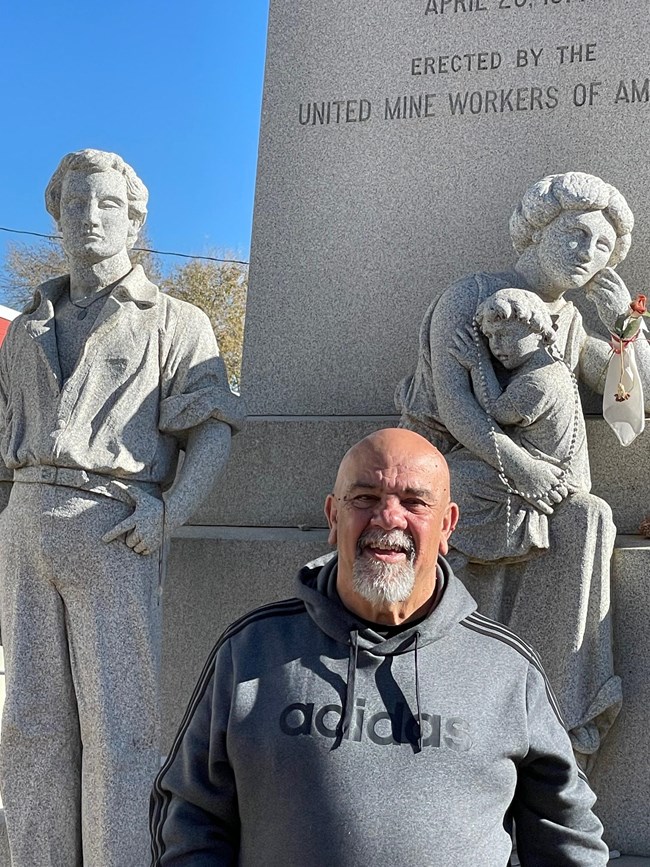

And I always think about as a historian, as a parent, what is the story that I think needs to live on until the next generation and what is the most important story that I would share? And it's this one probably. It's definitely on the top of my list. And it's really about why it's important for us to think about the people that are around us and their backgrounds and the living conditions that they're in. And I think this is where I love talking with Bob Butero because I think Bob has an amazing way of framing the importance of labor history and framing the importance of the work that United Mine Workers do. And this work is still extremely relevant to our nation and to our world today. And that hasn't gone away. And I think that piece of Bob at the end of his chapter of really talking about why does this still matter today? It didn’t end with Ludlow. It's going to continue on, and that there's still things to learn from the Ludlow Massacre.

History that Continues

Photo by Mike Tranter.

Photo courtesy of Karin Larkin

Catherine Cooper: Thank you both so much for sharing this history with us through the book and the podcast.

Karin Larkin: Thank you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.