Last updated: January 16, 2024

Article

Podcast 144: Uncovering the Work of Sara Plummer Lemmon, a Forgotten Botanist

Discovering Sara Plummer Lemmon

Image Courtesy of Wynne Brown

Wynne Brown: My name is Wynne Brown. I am a writer, editor, and graphic designer, and I am based in Tucson, Arizona.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us.

Wynne Brown: It's wonderful to be here. Thank you so much for inviting me.

Catherine Cooper: Could you tell us a bit about how you discovered Sara Plummer Lemmon and what drew you to her?

Wynne Brown: Yeah, I'd be happy to. Way back in, I think 2012 when I was working on the second edition of my book, Remarkable Arizona Women, I ran across a woman of the 1880s who was a botanist and an artist, and she's the woman for whom Southern Arizona's Mount Lemmon is named. She climbed the mountain in 1881 as part of her honeymoon at age 44. I thought that was pretty intriguing.

Image Courtesy of Wynne Brown

It turned out to be 1200 pages of Sara's handwritten letters. I made three trips to Berkeley and photographed them all and moved them onto my hard drive and then started reading them. I was just captured by Sara's observation, her voice, what appealed to her. And then when I also started looking at her artwork, and I have a background as a scientific illustrator, I was just totally captured by her and decided that I really, really wanted to do a book because I did not want her story to be neglected any longer.

Sifting through Primary Documents

Catherine Cooper: What was your process for distilling and working with such a large body of correspondence in Sara's collection?

Wynne Brown: I think every different biographer brings a different filter. To me, the fact that she was both a scientist and an artist was really one of the filters that really appealed to me. Also, the fact that she just completely reinvented herself because she was born in Maine, educated in Massachusetts, then educated more and worked in New York City and then moved to California at the age of 33 because of horrific health and that she constantly had bronchitis and pneumonia and decided that California would be a healthier place to live even though she knew no one there.

She just basically reinvented herself from a New England gym teacher to a Western scientist and artist. That whole transition was one of the filters that I used to go through all this material and try to see what are the pieces that I want to keep in order to build an accurate, fair story. With 1200 pages of letters and then everything else is there, you can't use everything, but you have to figure out what filter fits for the story, the particular story that you're telling about somebody.

Catherine Cooper: It sounds like both a challenge and a delight.

Wynne Brown: That sums it up perfectly. That's exactly what it was. She just grabbed me and I would walk around the mountains around Tucson or walk around town with her voice in my ear because she has a very strong voice. In the book, it was important to me to keep her voice and not inflict my voice on hers. And so that's a balance that's kind of tricky because I wanted to include enough of her words, yet I had to provide context for the readers so that they had a way of anchoring her into the world at that time.

Wynne Brown: I think every different biographer brings a different filter. To me, the fact that she was both a scientist and an artist was really one of the filters that really appealed to me. Also, the fact that she just completely reinvented herself because she was born in Maine, educated in Massachusetts, then educated more and worked in New York City and then moved to California at the age of 33 because of horrific health and that she constantly had bronchitis and pneumonia and decided that California would be a healthier place to live even though she knew no one there.

She just basically reinvented herself from a New England gym teacher to a Western scientist and artist. That whole transition was one of the filters that I used to go through all this material and try to see what are the pieces that I want to keep in order to build an accurate, fair story. With 1200 pages of letters and then everything else is there, you can't use everything, but you have to figure out what filter fits for the story, the particular story that you're telling about somebody.

Catherine Cooper: It sounds like both a challenge and a delight.

Wynne Brown: That sums it up perfectly. That's exactly what it was. She just grabbed me and I would walk around the mountains around Tucson or walk around town with her voice in my ear because she has a very strong voice. In the book, it was important to me to keep her voice and not inflict my voice on hers. And so that's a balance that's kind of tricky because I wanted to include enough of her words, yet I had to provide context for the readers so that they had a way of anchoring her into the world at that time.

Sara’s Legacy

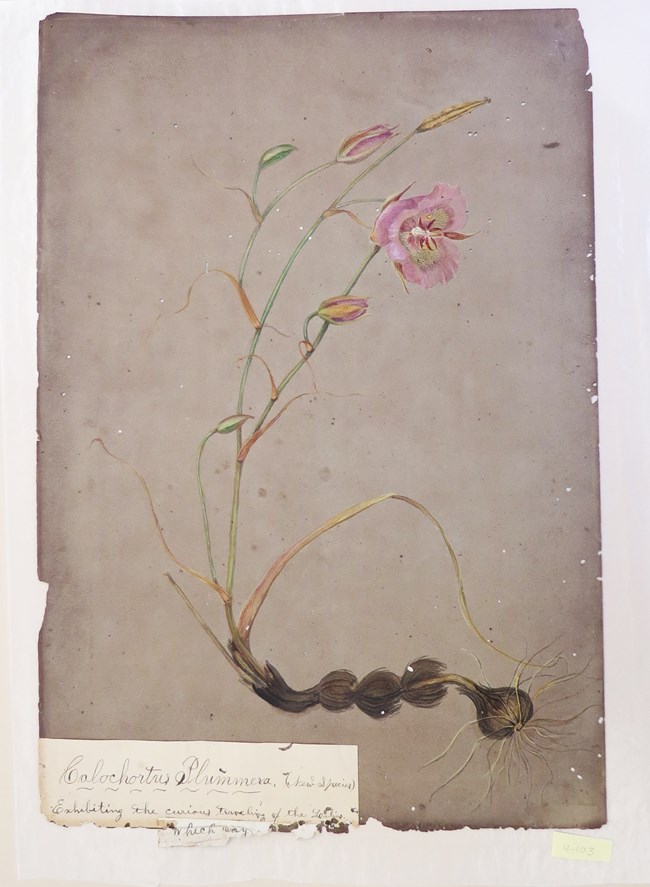

Photo by Wynne Brown. Original housed at University of California & Jepson Herbaria Archives, Berkeley, Calif.

Wynne Brown: It's such a shame because it's so typical of the time. For example, in the collecting labels of all the plants that they collected, they collected plants all over the West, and the collecting labels are all J.G. Lemmon and wife. Sara's name was not even included on their scientific discoveries. That's so typical of the times where women were just neglected and erased, their effect. I would say that basically her effect in conservation and suffrage and art and science were all just underrated because nobody knew about her.

Catherine Cooper: What would you say is the most surprising thing you learned during your research?

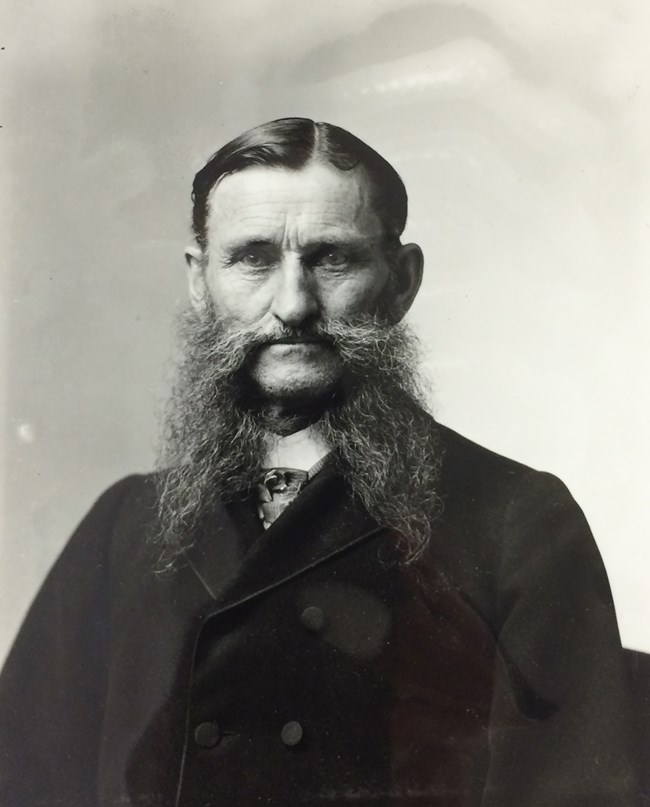

Wynne Brown: I think I would say her resilience. As I mentioned earlier, she had terrible health issues that her lungs were challenged and she was constantly sick. Her husband, John Lemmon, who went by J.G. Lemmon, had been a prisoner of war in both Andersonville and Florence after the Civil War. And so he was very damaged from his war experiences.

These two theoretically frail people managed to climb mountains and camp in wildernesses and go to incredibly remote places, and they just got an astounding amount done in spite of their frailties. I think that was something that really surprised me, and one of the things probably that I admire about her the most is her absolutely relentless curiosity.

Conserving and Sharing Sara’s Work

Photo by Dave Peterson, member of Team Sara and Wynne’s husband.

Wynne Brown: My husband jokes that he married two women, Sara Lemmon and me, because Sara still has not let go of me. When I saw her artwork for the first time back in 2017, there were two boxes that had been donated to the Berkeley archives. In these two relatively small boxes, there were 276 watercolors on paper.Some of them are in just terrible shape. Some of them have been munched on by insects who liked the paper but not the pigment, so that they look sort of like cutouts. And others of them survived the intervening 140 years really beautifully, and they're in the book.

But I resolved way back in 2017 that I wanted to do whatever I could to try to prevent those paintings from deteriorating even further. Through the generosity of a couple of donors plus putting all the proceeds of the book into it, I was able to raise enough money to travel back to Berkeley and to hire an art conservator whose name is Susan Filter to assess the paintings.

This isn't art restoration. This is really art preservation. Technically it's called rehousing and stabilization. It involves basically getting each of these watercolors into their own archival quality folder with a glassine sheet and then put in archival quality boxes so that they won't fall apart anymore. When I first saw them, the archivist hadn't even looked at the contents of the boxes because the paintings were so fragile they were afraid that by taking them out and counting them, that they might just crumble.

Last year, we went back in August. By that time, I had raised enough money that we were able to get the preservation work done on the first 276 paintings. Miraculously, amazingly, the archivist during COVID had discovered two more boxes of paintings, which was about another 200 or so paintings.

I hadn't budgeted enough and hadn't gotten enough funding to be able to finish those, but I'm really excited to say that thanks to a couple of very generous donors, we do have enough money now to go back to Berkeley this summer and finish up rehousing all of the work. I'm just thrilled by that, and especially since some of the work that we're now finding in those new boxes include some paintings from the Santa Catalina Mountains, and that's the mountain range in Southern Arizona just north of Tucson that includes Mount Lemon, which is the mountain named for Sara.

Catherine Cooper: That's absolutely phenomenal. This is a sideways question for you. Are any of the illustrations of the type specimens that Sara and J.G. discovered?

Wynne Brown: It's a little bit hard to say because they were casual about the geographic location. Nobody had GPS in those days, and sometimes they would indicate the location of the plant by where they were camping, and sometimes they were camping a mile or two from where the plant was actually located. So it's a little hard to say whether or not it was for the type specimen, but there are definitely examples of, for example, there's one of a morning glory, which was later named Plummer's Morning Glory in honor of Sara's maiden name.

Catherine Cooper: That's absolutely lovely. What would you like people to away from your book or from the work that Sara has left behind?

Wynne Brown: I think really my primary goal in writing the book is that Sara not be forgotten, that her story not be forgotten. I think that that's actually happening. I'm delighted to say that the book has done really well. It's now in its second printing. It won both a Spur Award and a WILLA Award. The Spur is for Best Western biography. The WILLA Award is for best creative nonfiction.

I wanted to write it in a way that was readable, and I think that succeeded from what people have told me. And I wanted people to really appreciate who Sara was, both as a scientist and as an artist. I think that also is happening. I think maybe one of the lessons that Sara can offer all of us is to really follow your interest and that reinventing yourself can certainly be a success.

Catherine Cooper: That is a fantastic note to have people think about. Thank you so much for talking with us today.

Wynne Brown: Absolutely. It's been such a pleasure, Catherine. Thank you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.