Last updated: September 12, 2023

Article

Podcast 131: Telling Stories in Museums

Storytelling for the Public

Catherine Cooper: Hello, my name is Catherine Cooper. I am here with...

Adina Langer: Adina Langer.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today, Adina. You recently published a book called Storytelling in Museums. Could you talk about how or where storytelling is in museums in the public awareness and then also in the GLAM fields [galleries, libraries, archives, and museums]?

Adina Langer: I would say that storytelling as an approach within museums has really come of age within the past 20 years or so. Museums have undergone a kind of paradigm shift from being places that are primarily concerned with connoisseurship and preservation of the most exquisite artifacts of the human experience or the natural world to one where they are primarily about education and engagement and helping people to understand their place in the world and how connecting with the past can enable them to better experience the present, to make sense of their lives. And so museums have become sites of communication, and storytelling is at the heart of that process; and GLAM fields are all related to each other in this endeavor. When I think about what museums do and where stories are captured, where they are preserved, where they are interpreted, where people make connections across that spectrum in the GLAM fields, each one has kind of a different piece of that puzzle.

So if you think about archives as sites of gathering and preservation and accessibility, the key being to make what is within a repository available to those who are seeking it, to those who can benefit from those kinds of connections. Many museums have their own archives or book special collections, same with libraries. Really it's this preservation to interpretation kind of spectrum. And then if you are on that interpretation side of things, how do you select what you are going to focus your energy on as an institution, and where do you draw your inspiration and how do you serve your community? Story gathering, storytelling, has increasingly become central to, I would say, all of the GLAM fields in that way.

Adina Langer: Adina Langer.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today, Adina. You recently published a book called Storytelling in Museums. Could you talk about how or where storytelling is in museums in the public awareness and then also in the GLAM fields [galleries, libraries, archives, and museums]?

Adina Langer: I would say that storytelling as an approach within museums has really come of age within the past 20 years or so. Museums have undergone a kind of paradigm shift from being places that are primarily concerned with connoisseurship and preservation of the most exquisite artifacts of the human experience or the natural world to one where they are primarily about education and engagement and helping people to understand their place in the world and how connecting with the past can enable them to better experience the present, to make sense of their lives. And so museums have become sites of communication, and storytelling is at the heart of that process; and GLAM fields are all related to each other in this endeavor. When I think about what museums do and where stories are captured, where they are preserved, where they are interpreted, where people make connections across that spectrum in the GLAM fields, each one has kind of a different piece of that puzzle.

So if you think about archives as sites of gathering and preservation and accessibility, the key being to make what is within a repository available to those who are seeking it, to those who can benefit from those kinds of connections. Many museums have their own archives or book special collections, same with libraries. Really it's this preservation to interpretation kind of spectrum. And then if you are on that interpretation side of things, how do you select what you are going to focus your energy on as an institution, and where do you draw your inspiration and how do you serve your community? Story gathering, storytelling, has increasingly become central to, I would say, all of the GLAM fields in that way.

Personal Stories and Larger Narratives

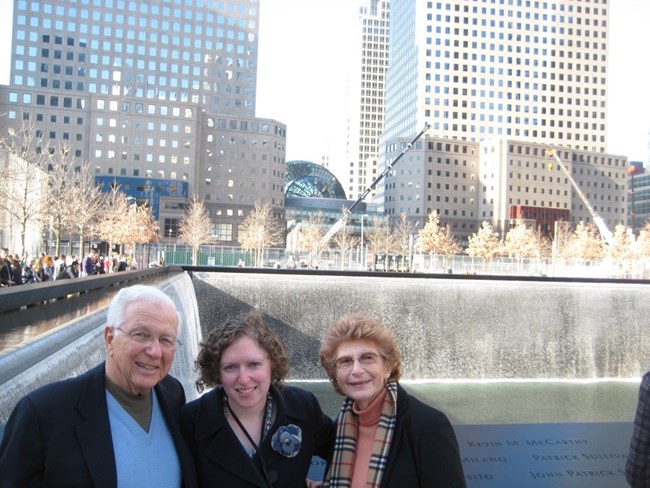

Image courtesy of Adina Langer

And I had seen that already at the 9/11 Memorial and some of the folks that we interviewed who had been responders, survivors, had passed since I had started there in 2006. And of course, in dealing with the World War II generation, we were really approaching the end of their natural lifespan. So that pressure was on us. And then what do you do then? What is your fiduciary responsibility as an institution, as an educator in both being the memory carrier now for these people who chose to share their stories with you? And then also understanding what the next generation doesn't know, what purpose bringing in diverse narratives can have in helping them understand the past. So I didn't want it to just be me. I actually reached out back then to history Twitter or museum Twitter, which was very robust back in 2015, 2016, and found some wonderful folks to be part of that original panel. Margaret Middleton, who is an independent designer and increasingly a scholar of the LGBTQ+ experience, and especially in museums and in public history.

I had contacts from the Tenement Museum, from the 9/11 Museum, and I found wonderfully through Twitter a contact in Australia who had managed multiple museums that were dealing with World War I memory and the integration of Indigenous stories. It was a great group of people to talk through these issues together. And I felt that just that panel, that there was more to do, there was more to say. So of course, segueing into the pandemic, I remember the day getting just the normal sort of outreach from AAM, "Hey, do you have a book idea? Something you've thought about doing?" Just a proposal. So I went ahead and did that and said, basically pitched that it was the right moment to capture the state of the practice. There were so many people doing amazing things in this area, why not create a book of essays that helped to illuminate what storytelling in museums is like in the 21st century?

Different Ways of Telling Stories

Adina Langer: As we were starting to move into the sort of second-third even decade of the 21st century. When my initial pitch was accepted, they basically said, "Hey, develop this further. What are your chapters going to look like? Who's going to participate? What's the overall scope of your project? And we'll let you know if we want you to develop it into a full book." So from there, I kind of reached out through all my networks of contacts, and my goal was diversity writ large. So both from personal perspective, diversity of people's lived experience and also diversity of the kind of museum professional they were or are. Were they working in education, curation, collections, social media, even sort of museum adjacent fields that weren't necessarily just engaged in creating exhibitions, in public programs, geographical location, etc. Lucky for me, a lot of my contacts back from graduate school and from my time in New York City had moved all over the country.

So I had this sort of built in geographical diversity through that. I had a wonderful contact who I had worked with in Morocco who agreed to write a chapter about the changing museum practice in Morocco in the 21st century. And then other people gave me other people. So I ended up with a designer who's worked in the U.S. and Canada and in various countries in Asia, and Margaret Middleton had moved to the U.K. So I had a little bit of an international element to this as well by the time I gathered all of these authors together. I've worked with the National Council on Public History on their blog History @Work for over a decade. So that was kind of what gave me the confidence to say, “Hey, I can edit a book.” I've done a bunch of editing, and I'm used to working with people who live all over the place. But I had never undertaken a project this big before. There was a lot of learning involved certainly.

So I had this sort of built in geographical diversity through that. I had a wonderful contact who I had worked with in Morocco who agreed to write a chapter about the changing museum practice in Morocco in the 21st century. And then other people gave me other people. So I ended up with a designer who's worked in the U.S. and Canada and in various countries in Asia, and Margaret Middleton had moved to the U.K. So I had a little bit of an international element to this as well by the time I gathered all of these authors together. I've worked with the National Council on Public History on their blog History @Work for over a decade. So that was kind of what gave me the confidence to say, “Hey, I can edit a book.” I've done a bunch of editing, and I'm used to working with people who live all over the place. But I had never undertaken a project this big before. There was a lot of learning involved certainly.

Shared Authority

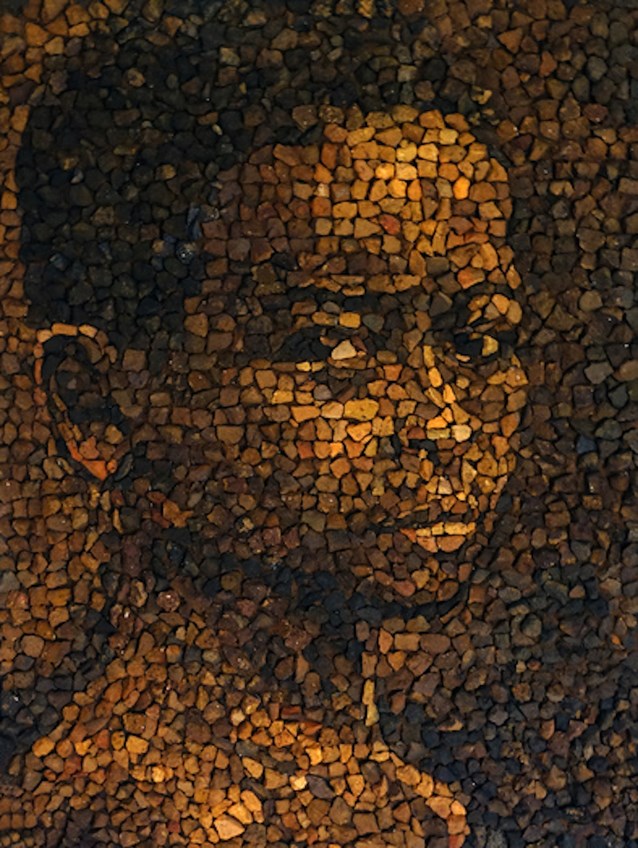

Image courtesy of Adina Langer

And a particularly powerful conversation facilitated by the National Council on Public History's Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Task Force, (I'm not sure if that's exactly the name), on this notion of ethics of care, made a really strong impression on me [This event took place on July 8, 2020 on Twitter and was called “An Evening with Aleia Brown.” https://ncph.org/conference/other-programs/an-evening-with-aleia-brown-twitter-chat/]. This idea that it is more important to listen perhaps than to assume in your relationship with historical story keepers. But at the same time thinking through, “okay, well then as a museum, what are your ethical responsibilities? Who are the people who have a claim on that process?” And that includes the people who are entrusting you with their artifacts and their narratives, and those are deeply related, but also the future generations that you're holding this material for. And that you're changing your interpretation and you're looking to help people who are coming to you as a bridge between their own lived experience and that of others who they want to connect with.

They want to understand, whether that's the people of the past or people from cultures that are different from their own. So the chapters in this book all come out of that moment where there is a really deep reflection and orientation toward engaging with the institutional wrongs, certainly coming out of the pandemic and the period in 2020 when there was so much looking inward. And also looking across, and some people were calling for “death to museums,” right? This idea of “are these redeemable, these institutions?” Are they incurably colonialist? Are they incurably racist? Can you overcome your origins by playing a useful living responsible role in society today? And I can say, having written a book and connected with all of these professionals, that my hope comes from a place of seeing the deep desire among professionals to do that work and to use whatever privilege that they have in society to make the world a better place from where they are, and to repair some of the wrongs that were done to and within communities and across borders, and to do that by listening and by speaking, both.

A Window into the Why and How of Museum Storytelling

Proun Design, courtesy of The Montpelier Foundation

So if you've ever seen yourself in a museum and you wonder... Or you haven't seen yourself, and you wonder why, I would hope that there would be something for you in this book. And anyone who's interested in kind of that peeling back the curtain on a process. I know when I grew up, I loved going to museums. I never thought about them as places where real people work. It was sort of that magical, like, “oh, this stuff just kind of appears and oh, it's so cool.” And I think that there are still people out there and museums still do multiple studies, and they're still incredibly well trusted institutions within our society, which is increasingly challenged when it comes to trust. And so for people who want to understand how museums do what they do, this book can really provide multiple perspectives on that.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much, Adina.

Adina Langer: You're welcome. Thanks for having me.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.