Last updated: July 19, 2023

Article

Podcast 130: Presenting challenging histories at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum

Starting a Holocaust Museum

Image courtesy of DHHRM

Felicia Williamson: My name is Felicia Williamson. I'm the Director of Library and Archives at the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum.

Catherine Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today. Could you give us a brief introduction to the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum?

Felicia Williamson: The Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum started as a small museum and education center in the basement of the Jewish Community Center in North Dallas in 1984. And it really was a reaction to what many Holocaust survivors in Dallas and the surrounding area saw as a misunderstanding, or even a lack of awareness, of the Holocaust. And they really wanted a place to educate mostly school children, but also the general public about the Holocaust, and also significantly a place to memorialize their lost loved ones. Because if you think about the eighties, traveling to Eastern Europe was not easy, and for many people, they didn't know potentially where their loved ones had been murdered, and there was not a place to remember or visit. And so there was a real sense of layered loss around that place. And so they established a memorial room and an education center and museum, and then that vision grew and there was a concept to move that museum and grow that museum, move it downtown into downtown Dallas, into a larger facility.

That took, I think, longer than they envisioned. And actually the new museum that we're in now opened in 2019, and we expanded to include human and civil rights, which was a really big jump. And with the understanding that the Holocaust was just a genocide of immense proportion, but also was the first time that human rights was legally recognized and protected in some ways. And tying that into our understanding of human and civil rights as a backbone, and then expanding our understanding of what does it mean to stand up for your fellow man or human, and how can we as individuals make a difference? And trying to actually embed the whole experience. So that's part of what we do. And then also trying to be a convener for tough conversations, which is another part of what we do at the museum. But that first group of Holocaust survivors was 125 people. The community was a little larger than that, but that was the group that came together then.

For a long time, the museum really was volunteer led, like many small museums, but we're professionalized now. So I'm the Director of Library and Archives, and in that position, I'm in charge of the library, which has about 3,500 volumes, and then I'm in charge of supervising and managing the oral history collection. We started recording oral histories at the very beginning. What's really cool about that is we have some of those early testimony interviews, and we've gone back and interviewed those survivors in their later years. Of course, they were already grandparents when we were interviewing them in the eighties, and now they're great-grandparents sometimes many times over, and they're much later in their elder years and have given their life even more reflection. So that's really an interesting piece of the puzzle. And so we have about 200 Holocaust interviews from North Texas Holocaust survivors, and then we have expanded our oral history collection to include human civil rights topics.

Expanding to Present Human Rights More Broadly

Felicia Williamson: When I think about human rights, that's the human condition, and it really includes almost anything. But we do in the exhibit have 12 strands of human and civil rights that we really do want to tie that back to. Then we have 20,000 archival and artifact objects in the collection. So the foundational collection was Holocaust related, so going up until I started collecting human and civil rights in 2018, but up until then was all Holocaust related. And then of course, most of those things are archival materials, photographs, albums, letters, and so on. But now when you think about human civil rights collections, I'm getting cell phone footage of mass shootings, protest signs. It's really changed the way we collect what we collect and how for a while it was very much a traditional archives with three-dimensional objects and photos and letters. Now I'm having to expand my scope of how I deal with things, but it's exciting and good, and I have multiple donor meetings a week, and we still bring in Holocaust related collections all the time.

We brought in a journal from a litigator at the Nuremberg trial that went on display. It was really significant, we brought that in and put it on display this month. So there's still Holocaust related content coming in, and people find things from their great-grandparents or grandparents or great-uncle, that still is evolving and coming to the surface. And then the human and civil rights pieces evolve, and we're becoming more known as a convener for those conversations and collections and testimonies too. So it's all moving, but sometimes different speeds and some starts and stops, I guess.

We brought in a journal from a litigator at the Nuremberg trial that went on display. It was really significant, we brought that in and put it on display this month. So there's still Holocaust related content coming in, and people find things from their great-grandparents or grandparents or great-uncle, that still is evolving and coming to the surface. And then the human and civil rights pieces evolve, and we're becoming more known as a convener for those conversations and collections and testimonies too. So it's all moving, but sometimes different speeds and some starts and stops, I guess.

The Importance of Trust in Storytelling

Felicia Williamson: I think in the archives world, the conversation is always based in trust. I think it is just multiplied when there's trauma at the root of that conversation with a donor or a donor's family. Same thing with an oral history interview. To get someone to share their story, you have to have a relationship built on trust to even get started. And then that's multiplied by some multiple over when there's trauma at the root of the conversation you're going to have and they need to trust that you're going to handle their story with care.

Collecting and Presenting Challenging Histories

Image Courtesy of DHHRM

So that has been a real adjustment, and by no means would I ever in a million years claim to understand the Holocaust. That topic is so immense. But I am more prepared and conversant in general on that topic because that is my academic background. And so it has put me kind of really in a situation where I want to learn more and be more conversant and prepared. And I also want to understand the communities I'm working with more. And then there's also a sense of how recent some of the trauma is. So if you have a Holocaust survivor, it's generally 75 plus years since the trauma. So the current survivors were children, which brings its own challenges. So if they're still alive, there were children when this trauma occurred and that, again, has its own challenges. And our team has been working with these individuals very carefully and professionally for a while now.

But when you have someone who, for example, was involved with a mass shooting here in Dallas a few years ago, or was a refugee from a recent crisis. That is a much more recent trauma and it's much more likely that they are talking to me about this for the very first time that they've ever talked about it. Now, it does happen that someone talks about the Holocaust for the first time in our offices, but it's just much more likely with these more recent traumas. So you just have to be really cognizant of that and prepared, and you can't really be prepared for everything that's going to happen. We do a process where we do a pre-interview where we try to understand the basic outline of someone's story so you can ask the questions that have meaning for the individual and for the historical context that you want to gather.

And I had done that in the course of the interview, the interviewee revealed something that was 10 time more traumatic than he had revealed in the pre-interview. Which I think is actually not uncommon and not a bad thing, and it was extremely powerful and also significant historically. But again, how do you prepare for that? That's impossible and it's not like you can plan. That's challenging. And again, instead of that interview taking an hour and a half, it took four hours. That's another thing when you're thinking about managing a department and time and resources and things like that. So some of that is just really challenging. Until you've built a museum, I don't think it ever really occurs to you. The theory is that you are prepared to present a topic to someone with a PhD or with a seventh grade reading level. All of that is compounded by the subjects we're trying to present, which is, I would argue some of the hardest subject matter that could ever be condensed into 16,000 square feet, which is the exhibit space that we have.

One of the things that's always struck me is I have a degree in history. You're taught to write to the level of 15 pages, 20 pages, but when you get into professional life, my bosses never want to see anything longer than one page. And if you're writing for museums, it better not be longer than a paragraph. And if you're writing for exhibit copy, it has to be extremely compelling to be longer than a sentence. So then you have to take all that learning you've had and unlearn it. Then you have to get these extremely complex subjects, and you can't assume anything about what people know and understand about these complex histories. Condense it way, way, way down, ax 90% of what you want to tell people. Then simplify the language without making it condescending and then present it and hope that they leave with maybe 10% of what you are trying to present, not because anybody coming through our doors is unable to understand the concepts, but because no one going into a museum is able to retain everything, me included. I mean, I'm a deep diver. I'm a museum junkie. It's just human nature. You can't digest that whole bunch of information.

Using Artifacts to Tell Stories

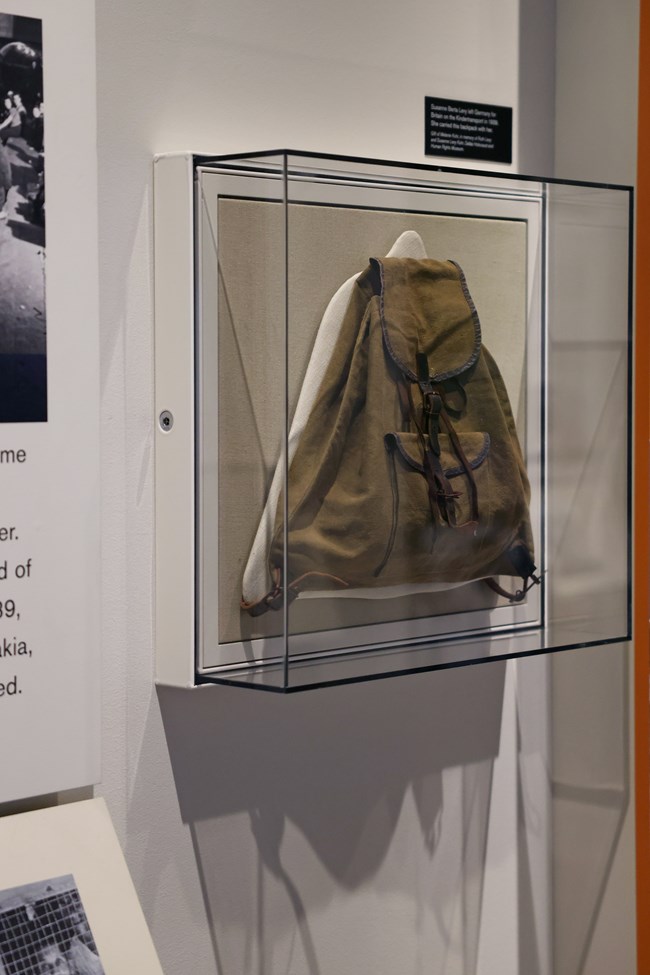

Image courtesy of DHHRM

And then they connect emotionally and intellectually with what that means. That means someone was so afraid that they sent their child away. So then that artifact is not just stuck in a glass case and just left there. It's helping tell the story. So that's my job, finding artifacts that help tell the story and so that they remember and it stays with them. If I find artifacts that do that, that's really the thing that matters a lot. And it's not automatic. There's lots of artifacts I love that I want to give their day in the sun. I really love them. But if they don't help tell the story of the panel work that we're trying to tell, then I can't put them in the exhibit. One thing I did when I was pivoting from being the Dallas Holocaust Museum to the Dallas Holocaust and Human Rights Museum, and I know this isn't for everybody, I cold called the 9/11 Museum.

Making Connections

Image Courtesy of DHHRM

If you're afraid you're going to get too many collections, that's not the fear. And that a lot of them had seen a very slow trickle that once that trust was established in the community you're working with, it would turn into a bigger wave. But that breakthrough had to happen over a longer time if there's trauma involved. And I think that's absolutely true, and that in a way, it'll seem like building those relationships will take longer and you'll have to build trust and have some positive exchanges before a more steady wave of sessions or testimonies comes in. And I've certainly seen that to be true. The other thing that's been interesting, if you think about Holocaust testimonies and even collections, it really seemed to escalate in the eighties. And if you think about legacy, that was when survivors were retiring. They're looking to their grandchildren. Holocaust survivors were not terribly interested, and they saw it as a burden. They didn't want to burden their children, but they didn't want their grandchildren to be unaware of this legacy or to not have access to this history. And so then you see these museums popping up and these collections being donated, and these oral histories being recorded when they have grandchildren. So sometimes it's not the best time to broach some of these subjects until people are ready to face it. If the history is worth preserving, then do the work. I just would encourage new professionals or younger professionals to have a creative sense of problem solving and to ask for help. If there's any defining characteristic of my life as a professional, it's that I've never been shy about asking for help. And I've been very fortunate to have received lots of help from very smart people across the field in all kinds of professional settings, whether it's academic, special collections departments, museums, all kinds of people who've really helped me along the way, offering their abilities and skills. And then I'm always willing to do the same because we're all really truly trying to get the same ball up the mountain, I think.

Catherine: Thank you so much.

Felicia: It's a pleasure.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.