Last updated: July 20, 2023

Article

Podcast 118: The Mystique of Florida's Key Marco Cat

Introducing the Key Marco Cat

Artwork by Merald Clark; courtesy of Merald Clark

Austin Bell: Hi I'm Austin Bell, and I'm the curator of collections for the Marco Island Historical Society.

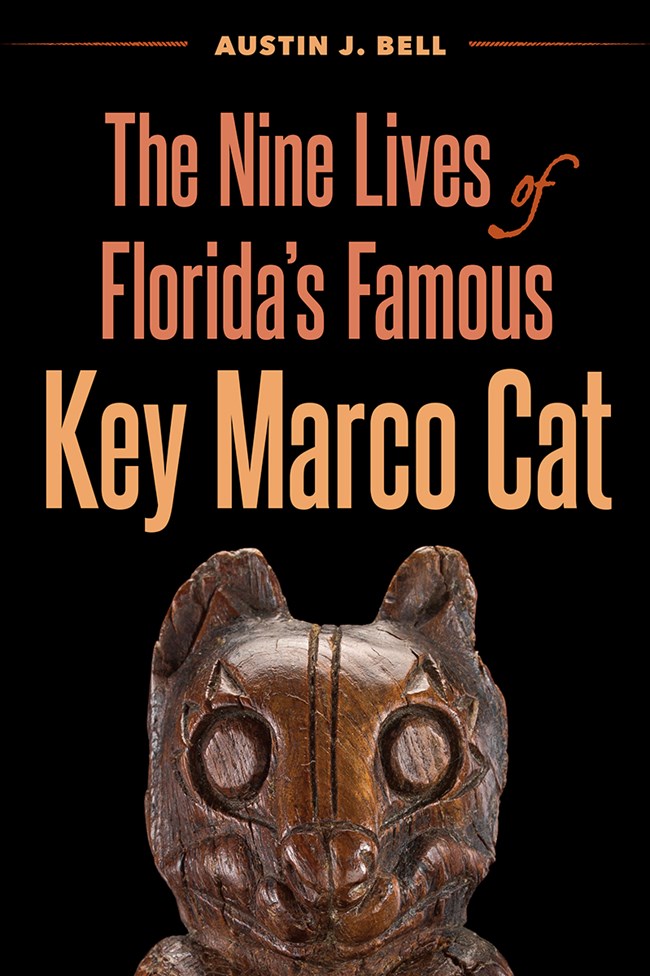

C. Cooper: Thank you so much for joining us today. You just had a book come out called The Nine Lives of Florida’s Famous Key Marco Cat. Can you tell us who, or what, the Key Marco Cat is and why it's so important in Floridian and American archaeology?

A. Bell: Sure, and I love the way you worded that question—the who or what—because the Key Marco Cat really is thought to be anthropomorphic, meaning it has both animal and human characteristics. But it's called a cat because it's generally feline in appearance, especially in its facial features. And essentially, it's a six-inch tall wooden carving that was likely modeled after—in part at least—a Florida panther and it's seated in sort of a crouching position resting on its hind legs, which are folded under, while its forelimbs stretch all the way down to the front of its torso and come to rest on its upper thighs. It's very small. It weighs less than half a pound, so about as much as a half-empty soda can. It's delicate, but despite those things it still holds enormous power and mystique.

It was likely carved by the Calusa people of Southwest Florida or their indigenous neighbors or predecessors. We don't know exactly who with certainty, but we do know it was likely carved at least 500 years ago because of the lack of European goods found at the site in context with the cat and other objects, but again are unsure of its exact age. It actually could be as many as 1500 years old. And it's extraordinarily rare because very few items of this sort of ephemeral nature have survived from that time period, let alone works of art like the cat made by a native artist at a time prior to the European invasion of the continent.

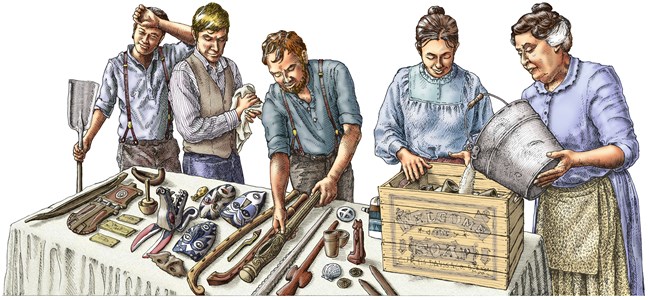

It was preserved in this oxygen-free environment at a muck site on what is now Marco Island where the museum that I work at is located. It sort of reminds me of those ancient peat bogs in Europe that preserved human remains in the level and the type of preservation. They found wood, plant fiber, gourds, even paint pigments still on objects in near perfect condition until they were excavated in 1896 by a Smithsonian anthropologist named Frank Hamilton Cushing. And they’re so important really because it’s the most complete and comprehensive assemblage ever discovered in a pre-Columbian Florida archaeological deposit.

And meanwhile, in the hundred-plus years since its discovery, it's kind of become one of Florida's most famous artifacts and it's had a sort of a fascinating history even since its excavation: being on exhibit in different museums and changing hands several times and all of that [is] sort of outlined in this book. On Marco Island, here it's also become sort of this source of local identity and pride because its image and likeness is really everywhere: it's on street signs, it's in jewelry, and it’s in local businesses. So, it means a lot, especially to the people of Marco Island.

Writing the Cat’s Biography

Image courtesy of Austin Bell.

A. Bell: You know, all museum artifacts and all material culture really has a life cycle and from the moment it's produced by human hands to the moment of its inevitable destruction. So, an object biography is basically the story of an object's life from its very beginning, or its birth if you will, all the way sometimes through to its end or death, which of course we haven't reached with the Key Marco Cat, thankfully. And so, I don't know if object biography is an official term or not and really I don't know a whole lot of other object biographies, quite honestly. The one that immediately comes to my mind is the film The Red Violin, which traces that object's history through time.

But it's something I thought was appropriate in telling the story of the cat because when I was thinking about it, I couldn't help but imagine all of the different sets of human hands that had held it over the centuries and how different contextually many of those hands were. And it just really struck me that the cat must have lived many different lives especially depending on the people and the circumstances surrounding it, which again vary greatly. So partially, you know, honestly for the sake of humor and intrigue, I organized the book into nine different chapters each representing a different life in what is this feline object's history. But, you know, of course, the true number of lives that it’s lived is not so easily defined. I started with the cat's origins and nature, really as part of a tree, you know it's a piece of wood, and went from there.

Object Mystique and Meaning

C. Cooper: Can you talk about the various meanings that have been ascribed to the cat over its various lives? One of the words you used in the book was transformative.

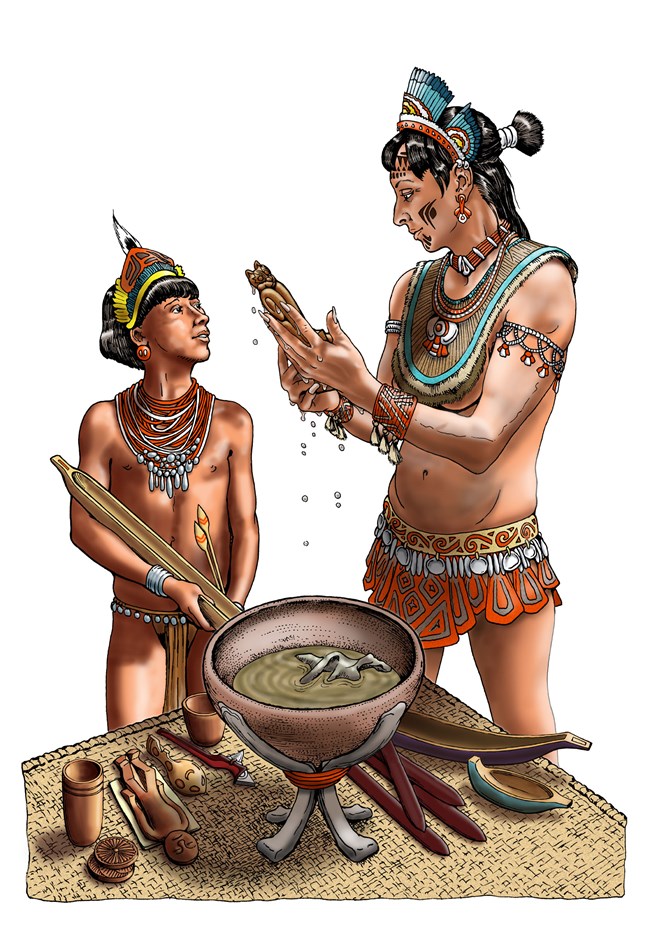

Artwork by Merald Clark; courtesy of Merald Clark

Artwork by Merald Clark; courtesy of Merald Clark

The Cat’s Future Lives

C. Cooper: So you mentioned that the cat has been on display more than 60% of the time. It is currently at your museum. What are the plans for the cat once it returns to the Smithsonian? Has there been any discussion?

A. Bell: I really don't know. There hasn't been much discussion beyond our use for it, which is incorporated into a larger exhibit right now, but that's something that will be up to the Smithsonian. I assume at first at least it will get some sort of well-deserved cat nap because it's been on exhibit for so long. And of course, one of the roles of museums is to extend the lifetimes of objects in their collections as long as possible so that future generations can benefit from them. So, you know, each museum is different I can't speak for the Smithsonian but I'll give you an example. The Penn Museum, for which I'm a consulting scholar, as an example they loaned some artifacts to us as well from the Key Marco site – equally as fragile and delicate – and their policy is for every one year that they're on display they need to rest for an additional 10 years. So, they're that fragile because they're sensitive to fluctuations in light levels, relative humidity, temperature, things like pests, and even vibrations from construction projects going on nearby are a threat to these fragile objects. And so, they're just trying to help preserve them as long as possible while educating people and making them accessible to people along the way. So, it's a balance but for the cat specifically I don't think it's going to be back in storage for long just knowing how in demand it is. You know, I imagine it'll probably be incorporated into other exciting new exhibits over the years, just as it has been for the past century. And you know, as the fields of anthropology and museum studies kind of evolve, which I talk about in Chapter 8 of the book, so too will the standards and practices for exhibiting this sort of material culture. And I just would be excited to see what those new exhibits look like and how they reflect those changes in these evolving disciplines.

C. Cooper: What would you like readers to take away from your book and will you continue to follow the cat’s progress?

A. Bell: I really don't know. There hasn't been much discussion beyond our use for it, which is incorporated into a larger exhibit right now, but that's something that will be up to the Smithsonian. I assume at first at least it will get some sort of well-deserved cat nap because it's been on exhibit for so long. And of course, one of the roles of museums is to extend the lifetimes of objects in their collections as long as possible so that future generations can benefit from them. So, you know, each museum is different I can't speak for the Smithsonian but I'll give you an example. The Penn Museum, for which I'm a consulting scholar, as an example they loaned some artifacts to us as well from the Key Marco site – equally as fragile and delicate – and their policy is for every one year that they're on display they need to rest for an additional 10 years. So, they're that fragile because they're sensitive to fluctuations in light levels, relative humidity, temperature, things like pests, and even vibrations from construction projects going on nearby are a threat to these fragile objects. And so, they're just trying to help preserve them as long as possible while educating people and making them accessible to people along the way. So, it's a balance but for the cat specifically I don't think it's going to be back in storage for long just knowing how in demand it is. You know, I imagine it'll probably be incorporated into other exciting new exhibits over the years, just as it has been for the past century. And you know, as the fields of anthropology and museum studies kind of evolve, which I talk about in Chapter 8 of the book, so too will the standards and practices for exhibiting this sort of material culture. And I just would be excited to see what those new exhibits look like and how they reflect those changes in these evolving disciplines.

C. Cooper: What would you like readers to take away from your book and will you continue to follow the cat’s progress?

Photo courtesy of Austin Bell.

Importance of Art and Culture

A. Bell: I think the thing about this that I would like most people to take away from it is just the fact that Southwest Florida, and really all of North America, was home for thousands of years to indigenous peoples that were complex and sophisticated and producing beautiful artwork that rivaled that of more well-known cultures, say in Central America, or Asia, or the Middle East, all around the world, right here in North America. And the difference in this case is that the cat, of course was made out of wood, a material that decays at a relatively fast rate comparatively so you don’t see it usually in archaeological sites. It makes you just wonder about all of the work that they did create across what we now know as Florida that didn’t survive in this miraculous archaeological context, because really it was. Key Marco, the site was sort of an anomaly to people. Archaeologists have been hoping for sites like that in the past hundred years with very limited success and it's really representative of just a tiny sample of the whole, vast expanse of material culture used every day by the Calusa and their ancestors. So, it's really one of the most important sites in the history of Florida archaeology, if not North America. You know, [it] just demonstrates that artistic complexity that I was talking about and so that's what I would like people to take away from this book.

Photo by Seamus Payne

C. Cooper: Thank you so much.

A. Bell: My pleasure, thank you for having me.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.