Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 105: Conservation and Community Use: The Collection Access Program at the Museum of Anthropology

UBC Museum of Anthropology

Collections Access Program at MOA

Catherine Cooper: The first question I want to ask you is what is the Collections Access Program at MOA and why is so important for MOA’s collections in particular?

Heidi Swierenga: The Museum of Anthropology is, what we would call in Canada, a medium size institution, and we have about forty thousand objects in the collections now from cultures from around the world.

The Collections Access Program is the work that we do within the institution to connect the cultures from which those objects came from to the objects themselves. It can take a couple different forms. Probably the most significant part of that program is the people that come into the museum.

UBC Museum of Anthropology

We host quite regularly elders gatherings, or community gatherings, sometimes school gatherings; different types of groups from different communities will come in to spend time with the belongings that they’ve selected.

So, a typical visit might be twenty elders coming down to see forty objects. And let’s just say it’s a basketry collection. So we might pull all those basketry pieces, put them in one of our research rooms, and then they have the day to work with them, and speak about them, and handle them.

The other type of collections access that we do is when we bring belongings out to communities for use. And most of my experience is around use in a Potlatch. Often that means that something might be danced, or presented, or processed as part of the business that goes on in the Potlatch.

Catherine Cooper: How did this program develop, and have you noticed it change as a part of the Truth and Reconciliation process that Canada has recently gone through?

UBC Museum of Anthropology

Lending Pieces for a Potlatch

Heidi Swierenga: It’s actually a program that has, I think, evolved naturally and very slowly. When we talk about when did this all start, we go all the way back to the early 1980s when then Senior Conservator, Miriam Clavir, had her first request to lend out one of the older pieces for use in a Potlatch.

And at that time in the early 80s this was a very, very different and new thing. For her as she talks about it, it challenged her and her professional training, because conservators are trained to make sure that an object lasts for future generations. And using something, even though it may be done gently and safely, there is always a risk that damage might occur. And prolonged use will inevitably change the look, or the aesthetic presentation of something that’s used.

So, for her, it started a decades long conversation about that balance between preservation and use, that now we as conservators are very, very familiar with. But that first loan turned into the next loan, that turned into the next loan, and the next loan. And now we do quite a bit of it.

And the second part of your question, how has this changed since the Truth and Reconciliation and the TRC, for people that might not be familiar with it, is the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission that was established to look at the residential school system, and the abuse and the damage and the fallout from that over several generations.

UBC Museum of Anthropology

Self-Determination

One of the big things that came out of the Calls for Action was, how have we, as an institution, met the directives of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights on Indigenous People. It was a challenge, and UNDRIP has been around for a long time; it forced a lot of us to say, “Have we thought about it? What have we implanted in terms of policies and procedures, that have addressed the primary directive?”—Which is that Indigenous people have the rights to say what’s going to happen about their cultural belongings, and the right to control the information about those cultural belongings.

And I think what we did is realize that we may have been doing what we thought was a pretty good job at working with our Indigenous communities, but we were being very passive about it. Yes, we were approving loans. Yes, we were facilitating these requests, but we were still doing it in a way that was convenient for us.

I think since the Calls for Action came out, we have taken on a more proactive stance, and we as an institution have recognized that we have the responsibility to make sure our program provides the resources and funds so that people can have the ability to travel to come see us. It’s a limited pot but at least we went after it and we made sure we’ve got resources there so that we can offset the costs associated with coming to the institution, or we can fully cover the costs that are associated with the insurance that is required when you travel a belonging out to a community. And it’s a priority for us. It is absolutely the number one priority for many of the people who work in the institution.

Catherine Cooper: How does the Collections Access Program, and particularly the loan of objects, balance the conservation ethics of preservation and use?

Heidi Swierenga: I think it does very well is the short answer. [laughs]

And maybe I can come at it from how we deal with the requests. So, when a request is made, let’s just say it’s a request to borrow a headdress from a family member that has the rights and privileges to either wear that headdress or have somebody dance it on their behalf at their Potlatch.

It is not such a complicated process, but it’s a process that involves several different people. So, conservators would be involved, a curator would be involved, the individual that’s made the request, and possibly the dancer who might be dancing that piece. And together, we’ll work out whether or not the piece is strong enough to be danced. Basically, what are the risks involved?

UBC Museum of Anthropology, photographed by Alina Ilyasova.

Preparing Cultural Objects for Use

And together as a group we’ll say, yeah it is strong enough, or we can’t quite attach the rigging that’s required in order for it to be attachable to the person who’s dancing and therefore safe, or we can, or maybe together we have to do some modifications to the piece in order for it to be strong enough to dance, or look in a way that is respectful for it to be danced.

So, for one example, myself, working with the late Kwakwaka'wakw artist and hereditary chief Beau Dick, modified a headdress only after he was satisfied that it was safe enough to be danced. When we first looked at it together, it was carved out of beautiful, thin hemlock wood and it, was cracked in several places.

He thought it was going to move around too much during dancing and was worried that it would deteriorate further, and he said, “Whoa, maybe not, maybe we should look at something else.” And I was able to say, “You know what, I think I might have a really simple fix for that.” And my conservator brain was saying, it has to be simple, it has to be observable, and it has to be reversible.

And I was able to do it quite easily just using tinted Japanese tissue paper and wheat starch paste. Once I did that, it was super, super strong and solid. And Beau said, “Yeah, that’s great. Now what I need to do is, re-carve the missing elements,” because he couldn’t present it in a way that he felt wasn’t respectable both to the object as well as the owner. So, he recreated the missing elements, painted them and then passed them back to me to stitch the whole thing back together again.

So, it was a perfect balance, in my mind, because we were both able to get at the point where we knew it would be safe. Yet we had to make changes to it in order for it to be safe. So, it’s not just preserved in its original form, it’s now different, and it’s showing the process that it went through. It’s showing the Potlach it went through, it’s showing that it was danced again, and it was able to still do the job that it was originally created to do, which was to show a certain privilege that the family wanted to show and be witnessed at that Potlach.

UBC Museum of Anthropology

Cultural Priorities Govern Approach

Catherine Cooper: How has your work as a conservator changed as these programs and initiatives have developed?

Heidi Swierenga: I would say that my personal process has changed quite a bit, and one story I can tell that illustrates this is… I was going to through some documentation for some belongings that are owned by a family who was going to be hosting a Potlatch. And when I went back to the file, I saw this memo that I had written when I was just freshly hired at the museum, so going on twenty years ago.

And this memo was in response to the first request for the loan of a particular headdress for the first Potlach that this family had had in several decades. And the memo that I wrote I feel now was appalling. It wasn’t really, but it was me as the young conservator who knew the best thing to say, and who knew exactly what had to happen, that well, yes, I think that it could be loaned but it couldn’t be used, it could only be presented because of a number of different issues. And it was in fragile condition and maybe that would have been the end result, but my quick answer was, “No, I don’t believe it’s possible.”

Now, that’s never how it would happen. Now, I would say, “I’m not sure. Why don’t you come in, let’s take a look at it together, see what you think?” And I would offer some thoughts, and they would offer some thoughts back, and together we would come up with a plan. But I read that memo and I thought, “My God, well I’m going to have to burn this. Nobody can know what I said.” And actually, I showed it to a colleague, and they said, “No, this is great, this shows how much we’ve changed, this shows how much our practice has evolved.”

And for me really, it shows how much I have learned from the different artists, dancers, and community members who I’ve worked with, who have taught me how to go about doing this properly. And I am grateful for all of those lessons, and grateful that I have something to go back to, to show my own students and say, “Look, this is one approach, and this is how you might rethink that and approach it in a different way.”

Catherine Cooper: So, what are some of the challenges of creating a program like this?

Heidi Swierenga: Well I think the most important challenge to overcome is the understanding that it’s important and the prioritization of this type of work over other things. Within every institution, that is such a challenge in itself because there are so many different priorities. Also, another challenge would be the connections to the communities for institutions that maybe didn’t have such strong connections.

I think the other big challenge for us, and it’s one that we’re still dealing with, is how do you get the information out? And that goes pretty deep. It’s not just letting families know that they can come and access the collections here, but families might not even know that their belongings are here. Many things have been taken from communities in different ways, a lot that was done within a period of oppression imposed here by the Canadian federal government and throughout the world. And family members may know that their belongings were taken or sold, but they may not know where they went.

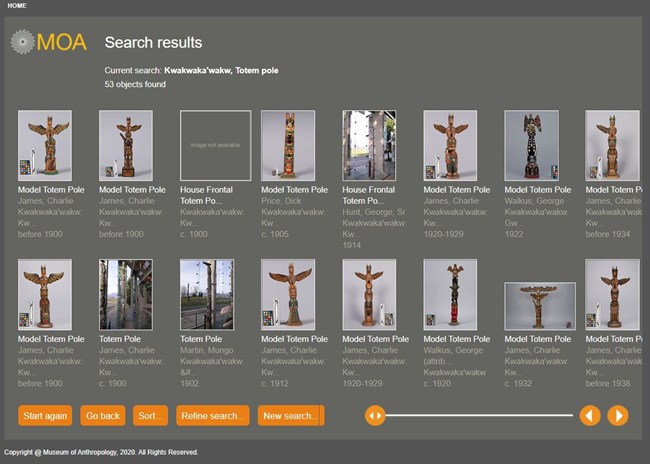

So, part of this is trying to facilitate that research process as people try to discover where their material culture now resides. The Reciprocal Research Network that was co-developed, MOA being one of the partners, is one platform that we support and that helps with that.

We also feel it’s important to make sure that our own home collection is digitized and accessible online through our collections Access System.

But that’s just one thing. How do you get the information out about the grants that you do hold? And what we’re learning also is, how do you write about it so people make sure they know that this information is for them?

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.