Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 093: The Caddos and Their Ancestors

LSU Press

Williamson Museum

Jason Church: Now Jeff, I know you are the retired regional archaeologist, but we’re sitting here in your office where you’re at work, so how retired are you these days?

Jeff Girard: I’ve been working on a grant from the Cane River National Heritage Area in the past few years working on the collections of the Williamson Museum.

Jason Church: So, that’s the repository here at Northwestern [State University].

Jeff Girard: Right. It was started in the early 20th century by George Williamson, and it is continued today. And there’s collections from all over the state, mostly from Louisiana, but some from other states as well. We’re trying to organize the collections now. They’ve accumulated for many, many years. It’s never been put into an electronic database of any sort, and that’s what we’re trying to do.

Jason Church: So, how many objects do you think are at the Williamson?

Jeff Girard: I have no clue. It’s in the hundreds of thousands, certainly.

Jason Church: Yeah. So, I want to talk to you today. You have a new book out, The Caddos and Their Ancestors, and subtitle is Archaeology and the Native People of Northwest Louisiana, Where They Are and Their Place in History. So, tell us a little bit about how you started, why you did this book, what it meant to you.

Jeff Girard: Well, I think the overall point is to give folks some sort of notion of the immense amount of time that people have lived in Northwest Louisiana. Our historic records only go back a couple of centuries, but we have evidence of people here for the last 12 to 14,000 years. That, of course, we know most of that time through archaeological research, through the study of the objects, and the alterations to the landscape that people left in the past. It’s a different perspective on the past. We don’t have specific individuals or specific events that we know about so much, but it’s more looking at changes in people’s life ways through that immense amount of time.

Jeff Girard: I did retire 2015 as the regional archaeologist. I worked for 26 years in this area, so I have a lot of information, and I also did public programs and I had little PowerPoint presentations that I would do on various topics.

Jeff Girard

The Caddos and Their Ancestors

Once I retired, I decided, well, I’ll try to put these together in some way. I didn’t want it just to go away, and I thought maybe I could do a website or something. So, I started to write little narratives linking the various talks that I did, and I realized, well, I might be able to make this into a book. I sort of wrote a few chapters and sent them to an editor at LSU Press, and they liked it and said, “Give us the rest of it,” and I did. So, that’s how it actually came about.

Jason Church: In the very beginning of the book, you use a really good analogy that I’ve never seen before about linking archaeology and objects to words on a page. Can you walk us through that analogy?

Jeff Girard: Yes. I’ve kind of thought that the point is to try to get people to realize that archaeology isn’t just collecting old objects randomly. People will bring things to me and say, “How old is this or what does this mean?” I say, “Well, I can’t really tell because the context is missing. I have to know something about how it was found and where it was found.” The analogy I use there is it’s like bringing individual words into somebody and asking what things mean, when it isn’t the words themselves so much, it’s how they’re put together in sentences, and how the sentences are put together in paragraphs that really provides meaning.

Jeff Girard

Artifacts to Context, Words to Understanding

Jeff Girard: It’s the same in archaeology. We can’t just look at individual objects and interpret them so much as we know their physical relationship, how they were found together, how they were found on the landscape, and also, try to get people to realize when they’re collecting things out there that that’s important that you take that out of context. You take that object out of context. It’s like taking a word out of a paragraph, and you just have a jumble of things that don’t mean anything. So, it’s the organization of the objects that we find are as important as the objects themselves.

Jason Church: So, I noticed one of the themes that sort of runs throughout the book is that a lot of these major sites were found when the landowner tried to build or plow up a mound on their site. Is that still a current issue today?

Jeff Girard: Oh yes. Alterations to the landscape that are going on today are just incredible and have been, and so we lose a lot of the archaeological record of the past in that. Also, sometimes we find things that we wouldn’t ordinarily find. But it is an ongoing problem, and it’s something where we know that it’s a limited database that we have. So, we try to look at what we can because it’s going away.

I think we’ve located most of the mounds. Some of them, the exceptions, might be places where they have been plowed down or eroded down, and there’s just a little remnant of them left, and those places we might find some interesting things that there once was a mound in a certain area, and we just got the lower portions of it left, and we might not be able to recognize that on the landscape.

Some of the older mounds, we’ve traced the Caddo culture back about a thousand years, as I point out in the book. There’s some other mounds that tend to be located up in the uplands, up in the hills, and sometimes it’s hard to tell if something’s a natural rise or it’s a mound. It’s something that surprises us.

Jason Church: If I’m a landowner and I run across the remnants of one of these mounds, what is the best thing to do?

Jeff Girard: Contact somebody; hopefully the Louisiana Division of Archeology in Baton Rouge. We no longer have a regional archaeology program. I used to be the regional archaeologist, but that was cut out by budget cuts a number of years ago. The best thing is to be able to contact somebody. Unfortunately, there’s not a lot of archaeologists out there. It’s difficult, but the people at the State Exhibition Museum, the Bossier History Center, museums, and sometimes libraries and stuff have the contacts where they can get to somebody who may be able to evaluate it in some manner or another.

What if a Landowner Finds a Mound?

Jason Church: So would you recommend, take a few pictures, go talk to someone?

Jeff Girard: Yes. Take a few pictures. Send them to the Louisiana Division of Archaeology, Cultural Recreation and Tourism in Baton Rouge, and they’ll be happy to take a look at it.

Jason Church: As you go through the history, what are some of the major sites in the Caddo culture that have yielded the most information for us?

Jeff Girard: Well in this area, going back before the Caddo culture, the earliest one that has been a major importance is a site called the Conly site, and it’s in Bienville parish below Lake Bistineau. It is very interesting because of its unique preservation circumstances. It was a place along a loggy bayou that was buried under 12 to 15 feet of alluvial clays. So, things are preserved there that normally don’t get preserved such as animal bone and plant materials. We know in detail what these people were eating at that time. And at that time, it’s also very interesting because it dates about 7,500 years ago, and it is one of the earliest places that we have a major archeological site in Louisiana. There are also human burials at the Conly site, and they’re the earliest burials that we have in the state of Louisiana, and some of the earliest in the southeastern United States.

That’s an incredible place. It gives us a look at a place very long ago, and gives us a look at it in very much detail that was just extraordinary. The preservation of bone was really good, and so we have deer bone, we have fish bone, even little fish and crawfish, and all kinds of things that got preserved underneath that clay. But, later on we have, as far as the Caddo sites themselves, we have places in north Caddo parish such as the Mounds Plantation site, which is still preserved very well. It’s on private property, but the landowner takes very good care of it. There are seven big mounds that were arranged around a plaza at Mounds Plantation. There are only two that are left that are of substantial size. Most of them are smaller or just been plowed down. But it is a site at the beginning of what we think of as the Caddo culture, and is some of the earliest Caddo pottery that we find.

In one of the mounds that was dug in the early sixties, there were burials in the bound of the leaders of the community, and they were buried with some extraordinary objects and beautiful pieces of pottery and other items that came from far away from other places. So, it’s a very interesting place. Contemporary with that, there was a place called the Gahagan site down in Red River Parish, and it’s been destroyed. The water washed it away in the 1940s, so it’s no longer there, but it also had a burial mound with extraordinary objects in it. Those are now at the Louisiana State Exhibition Museum in Shreveport. But, some of the items came from the Cahokia site in Illinois, which is across from St. Louis, which at that time, and we’re talking here about between about 1050 and 1200 A.D., it was an immense place. It was essentially a city and there was over a hundred mounds up there at Cahokia.

So, we have objects that came from there that made it all the way here into Louisiana, and they showed up at the Gahagan site, including objects of copper. Of course we don’t get copper around here naturally, but it came from where we got copper today in the Great Lakes region.

Jason Church: So, do you think the Caddo were traveling that far or were there trade routes between?

Jeff Girard

Pre-Caddo and Caddo Peoples

Jeff Girard: I’m not sure so much it was trade as much as it might’ve been people just visiting up there, pilgrimages, because the objects themselves aren’t sort of commodities, everyday things that you would trade. They’re very special items and very sacred items and they wind up in the burials of the leaders of the communities. So, I think that it was more of a—if people knew about Cahokia, knew there was this incredible place up there. So, a lot of people traveled up there and brought back things that were of incredible interest.

Jason Church: Yeah. It would have been quite a pilgrimage at that time.

Jeff Girard: You have to travel across the Ouachita and Ozark mountains to get up into to that area now, so immense journey. Of course there’s no horses, no wheeled vehicles of any sort. People had to either travel by water, which would have been difficult across the mountains, obviously, or they had to walk.

Jason Church: So, when we get later into the Colonial period where you had Los Adaes and Fort Saint John Baptist here in Natchitoches, you paint sort of a dark picture of what become of the Caddo and the Natchitoches Indians. Can you talk a little bit about that time period?

Jeff Girard: Up until when the French first got here in 1699-1700 and then established Natchitoches here 1714, it was mostly a still Caddo area. I mean there was just a handful of European colonists and everybody else was Caddos, and they lived throughout the area. The Caddos continued to be dominant in this area throughout until about middle 18th century, the middle 1700s, and then with the Spanish period after the 1760s, things started to change a lot. One of the problems was disease, the demographics. The Caddos lost much more substantially in terms of the population and even though the disease affected the French folks as well, they could replace the populations because more and more Europeans were coming into the area. But there weren’t more and more Indians coming into the area. So, demographically, they started to lose out in terms of overall population levels.

Also, they did become increasingly dependent on things such as firearms, gun powder, things they couldn’t replace. Instead of stone tools, it became iron tools. So, they had to trade and they were trading things like horses, livestock, cattle. They were stealing from folks in Texas and bringing it down here into the Natchitoches area, and eventually that was going down to New Orleans, and manufactured goods were coming up the other way. So, in the long run it was not good for the American Indian groups at all, and they became secondary when they were culturally dominant in the early 18th century.

The Europeans, the French, never enslaved the Caddos, I mean because they had trade relationship with the Caddos and the other groups. But what happened is really who bore the brunt of that was the Apaches; that there were the Comanches, Wichitas and Caddos were all taking Apache prisoners from Texas and bringing them into this area. Mostly, it isn’t like the African American slave trade where there was gang labor on plantations. It was mostly like women and children and things like that, a household of people. It was different than what we generally think of is as slave trade.

I tried to keep the book focused on archaeology and not try to write a history of the Caddos, because there’s been several others that are very good about Caddo history and go from the 18th century into the early 19th century. But one of the problems in the Colonial period is we don’t really have an archaeological site that we can say “This is where a group of Caddos lived in the 1700s,” so I do things like Los Adaes and I do things from Natchitoches here, and from a site up in De Soto parish that was actually lived in by a Frenchman named Pierre Robleau. He was married to a Native American wife, and they had trade connections because they were living amongst the Adaes, so one of the groups of the Caddos up there, but actually the archeological site that we have was a Frenchman. It wasn’t the Indians themselves.

Jeff Girard

Colonial Period and the Caddo and Natchitoches Peoples

Jason Church: You mentioned that, archaeologically, that a lot of the Caddo pottery during this time period takes on European forms.

Jeff Girard: Yes.

Jason Church: Do you think that was out of ease of trade? It was easier to trade with the Europeans if they have the European forms?

Jeff Girard: Yes. I think there was a market and that’s what the European people wanted. It’s mostly very utilitarian sorts of things like pitchers, and big storage jars, cooking bowls and stuff that would be stonewares in European terms, but there just wasn’t a trade. They were hard to get, so it was easier to get the Indian pottery for that. The relationship between the Caddos and the French was one of trade and it was a very important relationship to both groups.

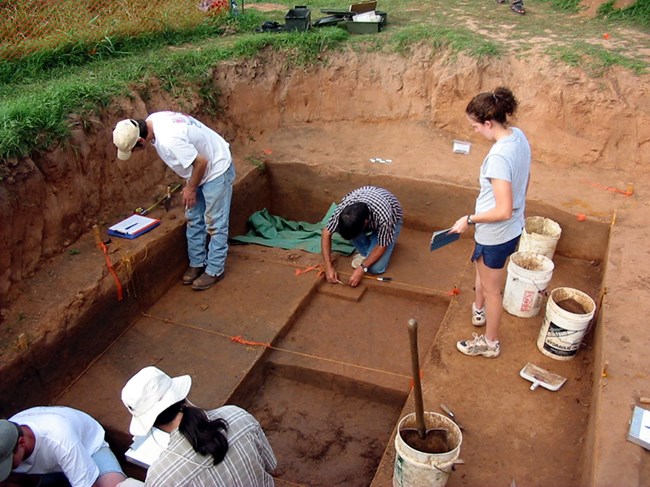

One of the things that people often ask about is what kind of houses did the Caddos live in and how do we know? The reason that we know is that the Caddos built houses that had posts in the ground. They put posts in the ground in a circular pattern and often times the posts, those houses, burned down and when they did, the posts leave a charcoal stain in the ground. So, if we excavate enough area, we can uncover the configuration of the house at its base.

Trade and Culture

As far as the upper part, we know from historic documents in the 18th century, mostly from missionaries in East Texas, what the upper part of the houses look like, and they were still making these in the 18th century, but they go way back probably a thousand years. They’re making cone shaped houses that are thatched with grasses. This style house goes way back and we can detect it through the archeological record.

As far as their economy, certainly beginning in the 10th or 11th century, we have evidence they started to grow corn and a little bit of beans and squash. They were doing probably some gardening of other plants even farther back in time than that. These plants would have been oily and starchy seed plants that were very nutritious such as sunflowers. We still eat amaranth, chenopodia, somethings that are weeds nowadays, but they do have seeds that you can eat and that are nutritious. But after about 1200 A.D., the Caddos were dependent on corn, on maize agriculture. That was very, very important to them. So, they were farming and living in settled villages. They also were continuing traditional food acquisition of hunting and mostly deer, but also small game rabbits and squirrels and things like that and fishing. Whenever we find a Caddo site where we have bone preserved, lots of fish bone. So, fish was very important in their diet.

Clarence Webb

Jason Church: You mention in the book a little bit about Clarence Webb.

Jeff Girard: Yes.

Jason Church: Tell us a little bit about Clarence Webb, who he was and what his contribution was.

Jeff Girard: Clarence Webb was a pediatrician in Shreveport, and he got interested, way back in the 1930s, in archaeology. I think one of his sons was a boy scout at the time, so he worked with his son. He dug some very important archaeological sites. He was one of the first to look at places where nobody else was doing it at the time, one of which is the Gahagan site back in the 1930s before that site was destroyed, that he’s the one who excavated in there.

He excavated at a site called Belcher up there north Caddo parish that I’ve described in some detail in the book because is it very important. It’s a later Caddo site. It’s between about 1500 and 1700 A.D. He also worked at the famous Poverty Point site in northeast Louisiana, which is now a world heritage area site.

Dr. Webb had sort of two careers. I mean he was recognized by professional archaeologists as one of the pioneers of the field. In fact, he formulated some of the pottery types that we now use all the time, and some of the way we put the archaeological record together, the systematics that we use for this area. It was Dr. Webb who first formulated that in conjunction with working with other professional archaeologists,

Jason Church: But he maintained his pediatric career.

Jeff Girard: Yes, yes he did and he was very well known. In fact, I think he was President of the American Pediatric Society at one time, so he had a very successful career in the medical field as well. I can’t remember when he died, but it was the early 1990s [1991], and he worked right up to that time. He donated his collections, his research collections, to Northwestern State University and we have them here, and that’s one of the things I’m helping catalog. Also, some of his libraries and his correspondence are in the archives here at Northwestern.

Jason Church: You were able to work with him.

Jeff Girard

Jeff Girard: I came here in 1989 and the first few years I was here, he was still alive and I was working with him a little bit as he got his books together and his papers together, and I would go up to Shreveport and meet with him and turn over things that he had organized. He was wanting to have things very well organized before he donated them.

Jason Church: Well, Jeff, thank you so much for talking with us today and telling our listeners a little bit about your new book from the LSU Press, The Caddos and Their Ancestors. We really appreciate it, and I highly recommended if you’re interested at all in not only just archaeology in general, but the history of Native Americans and especially the original occupants of Louisiana.

Jeff Girard: Right. Thank you very much.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.