Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 087: Shining Silver Part 2: Presenting the History of Gorham Silver

RISD Museum

This article continues from continued from Shining Silver Part 1: Conserving Objects for the Gorham Silver Exhibit.

RISD Museum & Gorham Silver

Catherine Cooper: It sounds like such a huge undertaking. So three years in preparation, and then it will be up for a few months here. What led the RISD Museum to actually decide to do something to this scale?

Ingrid Neuman: Well, it was interesting. I would say about six years ago or seven years ago, we hired a new curator of decorative arts and design. We hadn’t had a curator of decorative arts and design for quite a few years.

Elizabeth Williams came to us as a doctoral student, an advanced doctoral student, and she was writing her PhD on Gorham silver. So, it was a perfect match because she was coming to Providence where Gorham silver was first created by Jabez Gorham in 1831 or so, and then eventually the company was taken over by his son, John Gorham, later.

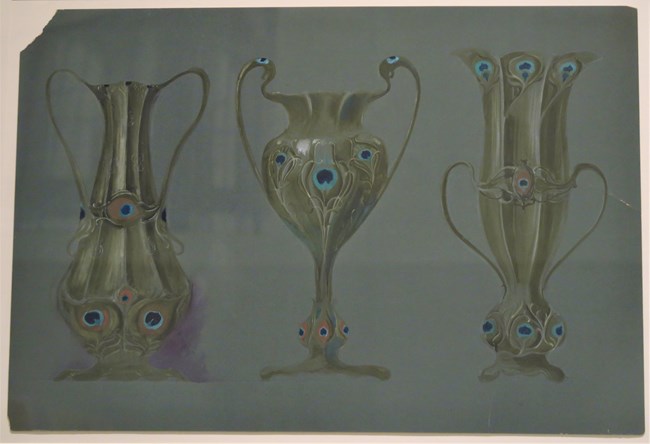

Elizabeth Williams, the curator of the exhibition, is a specialist of Gorham, and so it was a natural fit when she came to the museum. She knew of course that we had 2,200 pieces of silver, plus I believe about 2,000 design drawings that are very special because you see the 2D version of the elaborate silver artwork, and then you can also see the result of the design drawing. She was very excited by all of this, and it’s really been her life’s work.

RISD Museum

Design Drawings & Finished Silver

Ingrid Neuman: At least a dozen design drawings will be on view. The Gorham archives are located at Brown University right up the hill, so we’ve also been able to pull a lot of historic photographs from the actual company, which will be in the exhibition as well as in a beautiful book of Gorham silver published by Rizzoli.

We have a paper conservator here at the museum, Linda Catano, who is working on cleaning and repairing the tears and presenting the drawings in such a way that they won’t look like finished works of art. They’re really design drawings. They would’ve been tacked to the wall. They would’ve been very casual, not matted framed works of art. They’re working on a nice way to exhibit those so they look like design drawings.

This exhibit will be focusing in part on some very innovative techniques that John Gorham, the son of Jabez Gorham, insisted on. I think there was a little riff between the father and the son because the father was very traditional. Everything was done by hand. That was in 1831 up to about 1860 or so.

Then John Gorham took over and he introduced the steam-powered die-cutting machine, for instance, for the silverware. I get the sense from different readings I’ve come across that the father was much more of a traditionalist, and the son of course wanted to make advances, use mechanized processes to crank out the silver a little bit faster.

They were quite profitable. I think Jabez Gorham thought his son was going to take the company down, but the son was actually on the right track in that it was very profitable. The company grew from something like 40 employees to 400, this kind of thing, and actually had to relocate.

The original Gorham Manufacturing site that the father owned and operated was here in Providence, very close to the museum. That’s what’s kind of cool about the whole project is that we’ve had some walking tours. There’s a lot of history. It happened really right around the corner from the RISD Museum.

When the son decided to mechanize and the father passed the company to the son, they moved over to an area called Elmwood, which is further from the museum, but it’s still in Providence, but it’s just farther. They had to make many more buildings to accommodate the much larger number of employees.

The exhibit will highlight, I think, some of these new mechanized processes that the son introduced. There’s going to be a really interesting process area where you’re going to be able to see a lot of the dies, meaning these are molds that were used to press the silver into to create, for instance, the elaborate silverware.

When I say silverware, there are many unusual implements that I would say most people do not have today, for instance, fish forks, and knife rests that have little unicorn heads on them, and berry spoons that have raspberries wrapping around them.

One of the most fantastic sets of serving implements that you will see are called the Narragansett Salad Service. It’s a large spoon and a large fork that would be used to serve salad. The reason why it’s called Narragansett Silver Service is because if you look really closely, there’s little sea urchins, and snails, and all sorts of sea creatures that wrap around the handles in a really intricate pattern.

They’re just stunning. It’s not something that you would just look at for one second. You really need to examine them closely, and imagine people cleaning all the surfaces that are minute.

RISD Museum

Meticulously Cleaned Silverwork by Hand

Ingrid Neuman: We didn’t just put these pieces, say, in an ultrasonic cleaner, which, for instance, a lot of jewelers would do that if you took your jewelry to a jewelry store. We cleaned them by hand with minute pieces of cotton wrapped around bamboo skewers and very thoughtfully cleaned and in some cases didn’t clean areas that we left black to allow the higher levels, or the ornamentation that is raised on the silver pieces was cleaned to a higher degree than, say, the recesses so that you get the effect of these design elements popping off of the surface.

Catherine Cooper: Silver is an interesting material to work with for a wide variety of people. But for you, why do you find it so fascinating to work with?

Ingrid Neuman: Silver is interesting because of course it’s metal. Everyone knows it’s metal. I think people associate metal with being indestructible. It’s metal, but what people don’t realize is that metals have various softnesses and hardnesses.

For instance, silver is considered a rather soft metal.

There’s something called the Mohs scale of hardness, for instance, where all materials are rated by their hardness. There’s also something called the electromotive scale of metals where metals react with other metals in various ways based on their reactivity. There’s a lot to metals. I think that silver of course, we love silver in this country. Silver is loved in all countries. It’s a very precious metal. It’s soft. It can be manipulated in wonderful ways.

Gorham was very active. This particular exhibit will feature 120 years of silver-making. Not only did they use silver, they often gilded the silver, which we refer to as vermeil in French. The silver itself is, as you know, very sensitive to atmospheric pollutants, we call it, or chemicals that are in the air like sulfur.

That’s one of the biggest deterrents to keeping your silver shiny all the time. Sulfur can come from eggs, egg salad, eggs, or it can come from exhaust fumes from cars. It can come from burning coal in the 19th century. Sulfur has always been with us in different forms. That’s why the silver often tarnishes. It’s not only from sulfur, but often from sulfur.

When you add gold to the top layer, the gold of course is very sensitive. It’s very soft. It’s sensitive to abrasion. It’s not so sensitive to atmospheric pollutants. People know that, say, from gold wedding rings or other gold rings. They might wear gold jewelry. It doesn’t tarnish, so that’s why it’s very nice to have the gold on top of the silver. But it is sensitive to abrasion, and over-cleaning, and rubbing, and scratching, and that kind of thing.

Catherine Cooper: You mentioned that the Gorham Manufacturing is local to Providence. What did that do to the landscape here?

RISD Museum

Landscape

Ingrid Neuman: Right, that’s a really important element to consider when you appreciate all of the work that’s gone into these stunning Gorham pieces is that when the company moved over to the Elmwood area, the process of working with the gold in particular, it’s my understanding that the process working with the gold is actually a fairly toxic one. Vermeil, or gilding, when it’s applied to silver requires the use of some fairly stringent and toxic chemicals.

There’s many forms of applying gold to silver, but there’s amalgam gilding, for instance, that was done earlier on and is still practiced in other countries, is not practiced in America anymore because it used mercury, for instance, to apply the gold.

There was a process where you applied the mercury to the silver, put the gold leaf on top, heated the whole work to vaporize the mercury so it would go into the air. It was very toxic for the workers, and that is something to think about when you see the gold applied to the silver. That’s amalgam gilding. Amalgam gilding can be very lumpy. You see that on the Cubic Coffee Service, for instance. It’s a bit uneven.

Other forms of applying gilding by electroplating, for instance, which is what you see on the majority of the gilded pieces in the Gorham exhibition, was much smoother. It was a much thinner layer. It looks more clean basically.

It also required the use of chemicals like cyanide and different toxic chemicals like that which were toxic to the employee, but also there was leftover. There was residue. There was material that unfortunately was put out into the environment surrounding the complex, the Gorham complex, the manufacturing complex in Elmwood. To this day, it is an issue. There’s been many environmental cleanups.

There’s a body of water there called Mashapaug Pond. Then of course there’s the earth itself that has been cleaned and continues to be cleaned. The EPA is involved somewhat and other entities that are concerned about cleaning up. It’s a work in progress. It’s getting better incrementally, but it’s going to take a while, and it is an ongoing project. It is sort of a dichotomy of the beauty versus the toxicity of the implementation or application of gold.

Catherine Cooper: With some of these objects, and you also mentioned the son taking over the business from the father, how did Gorham promote itself? How did it keep the interest and keep people buying these pieces?

Ingrid Neuman: Well, it seems like they were very clever in making some wonderful standalone pieces maybe that were very unique. There was only one of them, they were unique, or there were only a few of them, six or seven produced.

For instance, a very good example of that is something called the Cubic Coffee Service, which you will see in the exhibition, which involves a tray, coffee, creamer, sugar. What was really wonderful about this piece is it’s faceted. It was important at the time that it was created because it basically mimicked the whole idea of skyscrapers, and building tall buildings, and this architectural innovation that was going on in urban areas.

The Cubic Coffee Service is unique. As I mentioned earlier, there were always design drawings for every piece and so forth, but we don’t own the design drawing for the Cubic Coffee Service. We own Cubic Coffee Service itself, which is fantastic.

However, during the course of this project, sometime in 2016, one of our staff members, I believe it was the curator, was watching Antiques Roadshow, as most of us do at the museum. We love that show. She was watching the American version, not the British version. A woman was on the show who had a manila envelope, out of which she pulled a folded design drawing of the Cubic Coffee Service.

It was just a match made in heaven because we didn’t know where the design drawing was. The curator reached out to the woman and so forth. The owner of the design drawing didn’t know where the actual Cubic Coffee Service was, which is here at the RISD Museum. We were able to borrow the design drawing for the exhibition, which is pretty fabulous.

RISD Museum

Gorham Lady’s Writing Table

Ingrid Neuman: We have a very special ladies writing desk and chair that is a composite material.

There’s 47.5 pounds of silver in the Gorham ladies writing desk, which is really hard to wrap your mind around.

Catherine Cooper: So, there’s pounds of silver. How much weight does the wood add to this desk?

Ingrid Neuman: Yes, we need to weigh it, and we will be weighing it prior to creating a crate because it is very important to weigh these pieces. Some of these pieces are quite heavy, as you can imagine.

The desk is also made up of a lot of different fruit woods, and also a fair amount of ivory, I’d say. We’re not the only one that has one of these gorgeous Gorham writing desks.

The museum in Dallas, the Dallas Museum of Art, also has a similar one I’m told. I have not seen it yet. It will also be traveling, so there will be two desks traveling with this show.

Catherine Cooper: Would that have been an object that they made a lot of?

RISD Museum

Admiral Dewey Cup

Ingrid Neuman: No, I’m not entirely sure how many Gorham writing desks there are in the world.

But for instance, you will also see in this exhibit a very large spoon in the Melrose pattern.

It’s solid sterling silver. Sterling silver is 92.5% silver, 7.5% copper.

Solid sterling silver, it’s not plated. It’s not just the surface.

This is a very, very large spoon.

It’s over a meter in length.

There were six or seven of those, for instance, produced.

They were promotional to get someone’s attention.

Perhaps you’d put it in a window that people would walk by in a city, that kind of thing.

I know the Cubic Coffee Service spent some time in a window to attract people to come in to purchase other Gorham pieces.

This particular spoon is very neat because it was used promotionally. They sat a small baby in the bowl of the spoon to express to the viewer exactly how large it is.

They also took this particular silver spoon to the zoo and used it to feed an elephant. These historic photographs will be visible. You can see them in the catalog.

In another example that I’d like to highlight, the Chicago History Museum has a wonderful Admiral Dewey Cup, it’s called, but it’s not a cup like you would drink out of.

It’s approximately six feet tall, and it’s made out of 70,000 silver dimes. Not all the dimes are recognizable as dimes. Many of them have been melted and reformed into basically a trophy cup. That’s what it looks like.

There’s an enamel pendant of Admiral Dewey. That’s why it’s called the Admiral Dewey Cup.

Anyway, they own this six-foot, 70,000-dime Admiral Dewey Cup, but we have the design drawing, which is also about five feet tall.

So, we’re bringing them together for the exhibition, which is really the point of the exhibition is to bring everything together and make it all make sense for the public so they can really understand from beginning to end how these beautiful pieces were created.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.