Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 083: 3D Documentation in Ladakh, India

National Park Service

NCPTT Internship

Mary Striegel: So, Satish, tell us, when were you at NCPTT?

Satish Pandey: It was way back in 2007. It’s been nearly nine years.

Mary Striegel: What were you working on when you were back there?

Satish Pandey: When I was there on a six week internship, I was working on a project which was dealing with looking at deposition of pollution gasses on limestone, treated limestone, so looking at the efficacy of consolidants and the impact pollution gasses in the atmosphere can have on it.

Mary Striegel: What was the best thing that you learned when you were at NCPTT?

Satish Pandey: The best thing that I learned, a couple of things. The best thing is that before being to NCPTT, I have never worked with custom-built equipment like the environmental exposure chamber that I worked on being in NCPTT. It had its own challenges to operate and get some good results on that machine, but it was one of the fantastic machine that I have ever seen. By the end of my internship, it started to give really nice data.

Mary Striegel: Well, you know, that was one of the things that people who’ve worked with that environmental chamber have always said, that after they’ve had some time working with it-

Satish Pandey: Absolutely.

Mary Striegel: … they see the beauty of the design of that instrument.

Satish Pandey: Yes.

Mary Striegel: Tell us, what have you been doing since you were at NCPTT?

Satish Pandey: When I was at NCPTT, I was doing my PhD at University of Oxford. I finished my PhD in 2010, then after that I have been a post-doctoral researcher for nearly two years with the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. I returned to India in 2011, towards the end of 2011 an of History of Art, Conservation, and Museology. It’s a small institution with three departments dealing with the history of art, conservation, and museology. I teach in the Department of Museology as a faculty member.

Mary Striegel: I had a chance to talk to you earlier this week about how you were using three-dimensional imaging. You might want to tell us a little bit about that.

Satish Pandey

Real-Time Deterioration in 3D

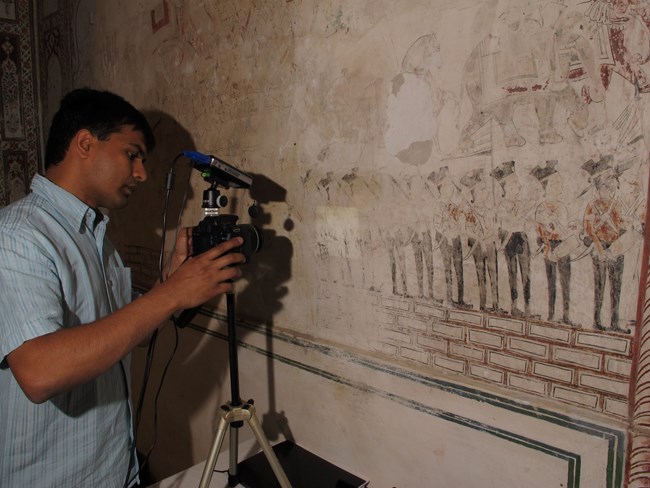

Satish Pandey: Yes. 3D imaging, when I started working in my post-doctoral research, 3D imaging was used by a number of people to record and document cultural heritage. Most of those work were dealing with documenting the entire monument, the entire building, looking at the fancy, three-dimensional data.

Now, when I started working on it, we tried to use 3D imaging to image small changes on timescale that happens in surface like wall paintings. Most of the wall paintings that I’ve been working on, they’re encrusted with plenty of salts and the problem of surface coating that people have put on the surface in previous conservation attempts.

The problem is, most of those coatings and salts are sensitive to moisture and changing humidity conditions. All those changes that take place during changing moisture, they have kind of temporal impact on that.

Every deterioration problem connected to salts and surface coatings can be monitored using 3D in real time. That is what I have been trying to, although we had some success dealing with 3D imaging of salts and surface coating, trying to monitor the changes that happen in salt crystallization over a short period of time.

Mary Striegel: That sounds like it was a really good project. Was that part of your thesis work?

Satish Pandey: No, that was part of my post-doctoral research.

Mary Striegel: I had a chance to hear a wonderful presentation you gave here at the AIC. I’d like you to tell us more about your most recent work, working with the monasteries. Tell us a little bit more about that project.

Sustainable Conservation

Satish Pandey: After getting back to India in 2011, I was trying to work with community to develop sustainable conservation attempts. One of the projects that I have been working on is in the northernmost part of the country, the region of Ladakh, which is a cold, arid landscape with almost nil rainfall. That was the kind of atmosphere until recently, but now we see a lot of climatic changes in Ladakh as well.

The real problem in Ladakh is, for the last ten years, the region has been open for tourism and there is plenty of tourist influx happening these days to see the cultural heritage that is part of that region. Most of the local people, who were not exposed to tourism and economic growth that has been happening across the country, are now suddenly kind of focused towards making more money coming from tourism. There are lots of other avenues opening, you know, and the uncontrolled development to sustain tourism and the uncontrolled way of exploiting the natural resources are creating disastrous situation for cultural heritage in Ladakh.

I have tried to work with community, trying to convince them to understand the historical value of the cultural heritage they have, rather than just the aesthetic and economical value. The economical value is the way that it is being exploited at the moment, given another ten years or so, the cultural heritage will be completely destroyed. Then there will be nothing for tourism to depend on.

Mary Striegel: We’ve talked about that there’s the economic pressures, but there’s also, with the tourists, there’s many visitors in short periods of time. You’ve mentioned that there’s also the lack of understanding of the traditional materials.

Satish Pandey

Satish Pandey: Yes. Most of the vernacular architecture in Ladakh is made with local materials: stone rubble, most of these are clay based houses. Even monasteries are made in clay, clay rendering. Nowadays, with changing pressure from tourism, people are shifting to modern and quicker materials, like cement concrete. Use of cement concrete, in many cases, has very different kinds of requirements. The reason is, in winter season, temperature really goes down to say about minus 30, minus 40 degrees Celsius. In a concrete housing, energy requirements are very high. The heating requirements are naturally very high, which has not been there with all these mud renderings. Mud being the natural heat insulating material, the energy requirements of that kind of housing was not too high.

Nowadays, with changing emphasis on tourism linking all these monasteries with transport system, with proper roads, has created a lot of problem in the local environment.

Mary Striegel: You also mention that there now are many groups trying to work there.

Satish Pandey: Yes. In the last ten, fifteen years, with the kind of attention the cultural heritage in Ladakh has got, there are a number of organizations, NGOs and people, working in Ladakh, trying to preserve the cultural heritage. All those attempts are sporadic. They all work in isolation, and there is no real information sharing that which group is doing what. There is a lot of funding coming from other countries, and people are very scared to share their information, and they are worried that their funding and their project may be jeopardized if they share information to other people.

That is a big problem. These conservation attempts, working really on objects, on paintings, on monastic objects, is not sustainable unless the custodians of the place, of the cultural heritage, know how to maintain and upkeep it. The problem is, you know, the monks and the local people around, they do not know what work is being done on the artifact. They do not know how to maintain it in future, after the conservation work is done. What happens in next few years, with the current practices that are happening in monastery, the cultural, traditional practices, the state of artifact that was either conserved or somebody has done some work on it, goes back to the condition it was before conservation. That kind of conservation intervention has really no long-term effect on it.

Mary Striegel: There are some short-term fixes going on, but no long-term strategy.

Satish Pandey: Absolutely. There is no long-term strategy trying to look at the holistic approach on sustainable conservation so that all these people who are custodians of the cultural heritage are aware about dealing with different conservation attempts and also the pressure that cultural heritage is having from the increasing tourism in the region.

Mary Striegel: Do you think that this type of problem is going on in other parts of the world as well?

Satish Pandey: Probably, probably, because tourism is a new industry these days. It is not that tourism has not been an industry in the past, but it is increasing these days, and materialistic view of exploiting cultural heritage might have adverse impact on cultural heritage in other parts of the world as well.

Mary Striegel: I want to thank you for taking time to talk to us today. Are there other things that you would like us to know?

Satish Pandey: The other things that I would like to say, that most of the places where we think of conservation, instead of looking at the conservation as a long-term solution, we also need to incorporate number of other things, like, for example, when I teach my students. There is an artwork. If I ask them, “Look at the artwork and tell me what you see,” the first thing, being a student of conservation, the first thing they notice is what is wrong with the artifact. During the course of noticing what is wrong with the artifact, what deterioration is going on in the artifact, they forget that, after all, it is an artifact. The historical value, the aesthetic value, naturally, they do not notice that. They think that, since I am teaching them conservation, I am expecting them to see conservation.

Conservation is not without looking at the historic and aesthetic value of the artifact. The first thing that we have to notice is the historic and aesthetic value of the artifact, and then we have to see, in the context of its values, how the conservation attempts are going to influence the entire concept.

Mary Striegel: That’s very good. Tell me again where you’re teaching and how many students do you usually have?

Satish Pandey: I teach at the National Museum Institute in New Delhi. Each year, we take about 15 students. On any given time, I have nearly 30 students who are studying art conservation.

Mary Striegel: They’re very fortunate to have you, Satish.

Satish Pandey: Thank you so much.

Mary Striegel: Thank you, again.

Satish Pandey: Thanks a lot. Thank you so much.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.