Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

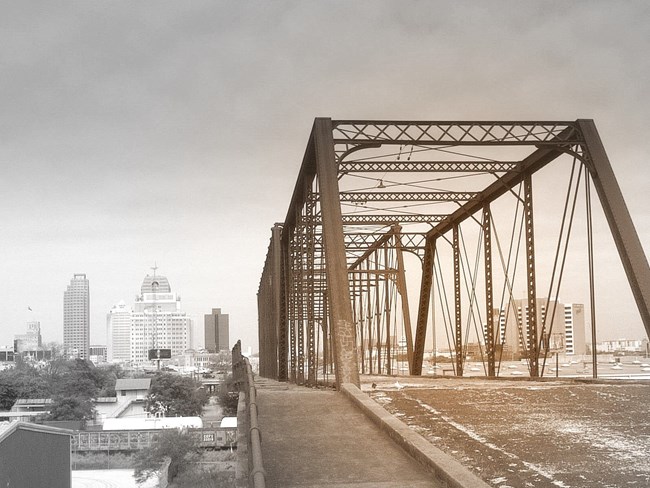

Podcast 030: Texas Dancehall Preservation and the Restoration of Hays Street Bridge

Patrick Sparks

Patrick Sparks and Preservation Engineering

Andy Ferrell: Good afternoon and welcome to the podcast Patrick.

Patrick Sparks: Thanks, Andy. Glad to be here.

Andy Ferrell: I’ve known you for some time, and I know that you are passionate about the engineering aspects of historic preservation. How did you get involved in preservation engineering?

Patrick Sparks: I was an aerospace engineer at the beginning of my career, and so when I was about 25, there was a time when I decided I needed to look a little bit differently at my career, and I thought well, does anybody ever study the problem of what do you do with all the stuff that we build–or have built. So, I got interested in that and then it occurred to me to go back to graduate school and I did.

Patrick Sparks: I met David Woodcock at Texas A&M. At the time he was head of the preservation program there, and he welcomed me with open arms as an engineer interested in studying preservation. What I found was that historic preservation was really the only discipline at the time–and really still now–that has a formal set of principles about how you take care of the built environment. So that’s really what appealed to me and going back to graduate school to a program like that was just the perfect thing. After that it took me awhile to build a career in this area, but it’s the most satisfying thing I’ve ever done.

Role of an engineer in preservation projects

Andy Ferrell: You can’t ask for much more than that, I don’t think. So, in a nutshell Patrick, tell us what is the role of the engineer in preservation projects.

Patrick Sparks: For me it’s really about first, setting the diagnostic protocol. That is, figuring out or helping the team of professionals and contractors, to figure out how to know what’s wrong or right with the building or bridge.

Hay Street Bridge

Andy Ferrell: Funny you should mention bridges. I know that you’ve just been involved in this exciting Hay Street Bridge rehabilitation project. Can you give us some background? What have you been doing in that? What’s special about this bridge?

Patrick Sparks: Well, it’s a really a cool bridge. It’s called the Hay Street Bridge or viaduct, and it’s in San Antonio, Texas and it consists of two 1881 wrought iron truss spans that were relocated to San Antonio in 1910 to construct this really long viaduct over the railroad tracks.

Patrick Sparks: It was built at a time when there were more and more trains and of course there was more and more vehicular and pedestrian traffic, and so there was a conflict at the grade crossings. So the city compelled the railroad to build them a viaduct. The railroad chose to reuse these two old spans and then build the approaches, about 1000 linear feet of approaches, out of reinforced concrete. It’s really a pretty substantial structure and it connects a historic neighborhood with downtown San Antonio, across this very active railroad track.

How did you get involved?

Andy Ferrell: So how did you get involved in this project?

Patrick Sparks: Well about eight years ago, in 2002 or earlier, we were asked by the city of San Antonio to give them some background information on truss rehabilitation so we did that, because they were looking for grant money at the time, process of applying for the grant money, and so we took them and showed them another project of similar aged truss that we had rehabilitated and just talked over some of the options.

Patrick Sparks: Then later, when the request for qualifications came out, we submitted our qualifications and competed against other firms and were selected to be the consultants for rehabilitation design. That was in 2002 and we just now finished the project. So, it was a pretty long project although the construction, rehabilitation construction, only took about ten months.

Was the rehabilitation envisioned as a pedestrian-only bridge?

Andy Ferrell: Now Patrick, in the beginning of this, did they ever consider continuing to use the bridge or reusing the bridge for vehicular traffic or was it always from the beginning of the rehabilitation, envisioned as a pedestrian bridge?

Patrick Sparks: Andy, early on, I think that there were some thoughts about that because the bridge actually wasn’t in vehicular service until 1980 approximately. So, there really wasn’t any reason from our point of view, that it couldn’t remain in vehicular service but by the time we got involved, the State Department of Transportation and the owner of the bridge, City of San Antonio, had agreed that it would be only a pedestrian and bicycle bridge.

Patrick Sparks: They did explore the options of relocating the historic truss spans and several other options during the feasibility study phase, but I honestly think that it certainly could have been a vehicular bridge again. I think generally if we just go back a little bit and talk about bridge rehabilitation in general, we want the bridges to remain in vehicular service if they can. In this case, we thought that they could, but it was a decision that we didn’t have full charge of, but it does make a very good bicycle and pedestrian bridge.

Patrick Sparks

Advice for saving other historic bridges?

Andy Ferrell: We’ve talked a little bit about this before, and there are lots of historic bridges across the nation that find themselves sort of in the same circumstance. What lessons did you learn in this project that you would share with those folks involved in efforts to save their historic bridges?

Patrick Sparks: Be patient and keep trying. You know these trusses, well one of the trusses, there’s two, one of them is a Whipple, the larger of the two is a Whipple truss, which is a particular kind of truss that was fairly common in railroad and highway bridges in the late nineteenth century, but it is no longer common at all and there’s just a handful of them left in Texas and really not that many nationwide. In particular, this Whipple truss is made both of wrought iron for the main members and then cast iron for the joint blocks that connects those members.

It’s really rare, even in the United States as a whole, there’s just very few of those bridges left. So that truss has a very high level of significance. Now, I bring that up because an engineer, a fellow named Doug Stedman, who is very well known in Texas and is retired now, is the one that identified those trusses as being historically significant and really rallied the community and just the local citizenry and the engineering community to get behind this project as something that was very important.

Patrick Sparks: Doug’s perspective on it was these were engineering landmarks, and he was successful in getting them designated as such through the American Society of Engineers. So they are not only eligible for the National Register, they are also listed as civil engineering landmarks. More importantly, it’s grass roots, people have got to want to keep their old bridges and that’s really the essence of keeping them and saving them even in the face of opposition from powerful entities like the state DOT’s or the Federal Highway Administration, or the municipalities, or the railroads; whoever is pretty determined to replace things. We see that in buildings also.

Patrick Sparks: It’s the same struggle preservation-minded people face but bridges get pretty much replaced or used to be replaced without anybody noticing it, and we’ve lost about half of our historic bridges in the United States over the last twenty years. So, the heritage of historic bridges is at risk. It’s important for people to, somebody identify the resource, the historic bridge, and say, okay, this is important. Then if people can get behind it, then to stay with it, hang on, and follow the available process like the Section 106 or another one called 4F which applies to bridges, and for citizen involvement to get people heard about what’s important about the bridge. It’s not easy to save a bridge, in fact, I’d say it’s harder than saving a building because the use alternatives are pretty narrow. There are a few examples of doing something other than using a bridge as a bridge, but mostly they kind of like to be bridges.

Andy Ferrell: Sure.

Patrick Sparks: And that’s what I tell people. You know bridges want to carry people and cars and animals over some obstacle, whether it’s a waterway or road or railroad. That’s what a bridge wants to do and that’s what we really would like to keep them doing. So having to work with such a beautiful bridge and one that was made of wrought iron and cast iron, which is very durable, and you get to see the historic workmanship and the engineering genius that went into these things.

Patrick Sparks: It’s really amazing to go back to how this one was saved, Doug Stedman, engineer retired, well known, identified the bridge and he said, “Well look, we need to save this,” so he worked tirelessly for over two years to save the bridge and raise monies, and he and a group of people in San Antonio, including the Conservation Society, raised about a quarter of a million dollars to help offset the cost of the project, the matching portion, and they were able to go and get a grant, to win a grant from the DOT.

Who were the partners in this project?

Andy Ferrell: Patrick, I was just going to ask you, who were the other partners involved in this project?

Patrick Sparks: Well, there are quite a few, so at the grassroots level, Mr. Stedman and the entity of engineers in San Antonio and the San Antonio Conservation Society helped in raising money. The city is the owner of the bridge; the City of San Antonio owns the bridge. The Texas Department of Transportation is the funding agency. They provided the transportation enhancement grant, and they also provided some oversight to the project in terms of design review and construction inspection.

Patrick Sparks: Then as consultants, was my firm, Sparks Engineering was the prime consultant and structural engineer of the project. We also had landscape architect, Bender Wells Clark out of San Antonio, and Garcia and Wright, civil engineers, and Joshua Engineering Group, electrical engineering consultants. Then the bicycle community was really behind it and, this is very important, the neighbors were very involved. This is a very distressed historic neighborhood that has been badly impacted by things like warehouses, and the neighborhood is a historic neighborhood but it’s gone downhill. But, there are changes coming, and this bridge is part of that, so people are now moving back into the area and they’re fixing up the houses and there is some improvement.

Patrick Sparks: The bridge is part of that improvement to the area, and I think the bridge was very important as a symbol of the community and that the community really is still vital and the bridge is seen as a landmark in this neighborhood. I think that the community support was overwhelming and that really drove the project and drove a lot of the things that we did in terms of the choices we made. For example, the approaches which are made of concrete were not only deteriorated, they were built in 1910, and they were severely deteriorated and really could not be saved, but moreover, they were really right in front of the neighborhood houses.

Patrick Sparks: The approaches are just your big wide 30 foot concrete bridge approaches just descended right into these neighbors’ front yards basically. And so it was really an awful place created when the bridge was built in 1910 and consideration was not generally given to or being sensitive about what the neighborhood would be like after you built something. So really there were a lot of problems when the thing was done originally, and we had the opportunity to fix that. We made the approaches much narrower.

Patrick Sparks: Instead of 30 feet wide, we made them 15 feet wide, which is what we needed for pedestrians and bicycles. What that allowed us to do, because the approach spans are elevated; this allowed more light to come in, more space, more light and you don’t feel that the bridge is oppressive anymore, and it gave the neighbors a lot of room in front of their houses. Now that space in front of their houses is landscaped and it’s beautiful and people really respond to how narrow the bridge is.

Patrick Sparks: But we followed the basic profile and layout of the original bridge, and we found some ways to echo the theme, kind of the architectural theme of the 1910 concrete bridge in terms of its clean lines and rhythm and the little cantilevered brackets that stuck out in 1910, we replicated some of that or we interpreted some of that per our design so that we have a really nice rhythm in those approach structures, which that rhythm leads you right up to these historic iron trusses which are the centerpiece of the project.

Texas Dancehall Preservation, Inc.

Andy Ferrell: Excellent. Well that sounds like a really great project Patrick, but I want to sort of do the lighter side of preservation now, because I know that historic bridges are not the only thing that you care about preservation wise. I want you to tell me a little bit about the Texas Dancehall Preservation, Inc.

Patrick Sparks: The dancehalls are my favorite thing and to anyone who’s listening, you really have to come to Texas if you want to understand what Texas is and who Texans are — you can go to the Alamo and the Stockyards and stuff like that but if you really want to know, you go to a dancehall. It happens that Texas has more traditional dancehalls than any place on earth. We think that there are probably, maybe 500 left out of a historic thousand or so that have existed in the past and the dancehalls I’m talking about are traditional community halls that were built by German, Czech, Polish, and other immigrants that came in the in nineteenth century and brought with them a heritage of social dancing.

Patrick Sparks: That nineteenth century heritage is still alive in many parts of our state. So a few years ago myself and a couple of other people realized that what we had was a really unique resource in these halls that still existed, though many of them are not used or only used rarely, but to a large extent the social and cultural vitality is still there. When you go to one, it is like going back a hundred years and there are young couples and little kids and grandma and granddad, the whole family is there dancing. So several of us got together and we said this is very important to save, so we set up a 501-C3 non-profit corporation called Texas Dancehall Preservation, Inc. with a mission of trying to save all of the traditional dancehalls in Texas. It’s a good time and we would like everybody to come down and go dancing.

Andy Ferrell: Excellent. I’m ready to come myself. In fact, my next trip to Texas, I’m going to get in touch with you ahead of time. Well Patrick, it’s been a lot of fun talking to you today. Thank you very much.

Patrick Sparks: Thanks a lot Andy. It’s great talking to you.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.