Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 023: NCPTT Interns Talk About Their Summer Research

National Park Service

Anna Muto: Hello, my name is Anna Muto, and I’m a recent graduate from the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Va. This summer I’m an intern for the materials research program at the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training. My particular research focuses on rust converters.

So, what happens is a rust converter is a product often based in tannic acid or phosphoric acid. And it reacts with the iron-oxide in rust, and together they make a whole new layer that is extremely protective and helps to prevent future corrosion on any objects. This project is particularly applicable in conservation, as there are so many different historic items and cultural items that we need to protect from rust and from corrosive damage.

During this project, I’m hoping to get a little bit more of an understanding of what it’s like to really work in a conservation lab. So far I’ve really enjoyed the chances that I’m getting to work with different instruments, with different chemical concepts and apply all of these to one simple problem in the bigger world of conservation. I’m also hoping to be able to contribute something in the long run to the work that NCPTT is doing for their particular projects, but also that apply to so many other projects in different firms and across the country.

National Park Service

So to accomplish these goals of my research project, we’re doing a couple different things. The three main parts are:

We have these wonderful samples of rusty metal, and what we’re first doing is we’re documenting the metal through each of these different steps.

So we do a lot of photography, we’re also doing some chemical documentation with laser profiling so we can get a nice map of the surface as well as using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer, which is a fancy way of saying we “zap” it get a reading and from the reading it should tell us what the primary chemicals are.

So we use these to document what is happening in the object, but then we also do a couple other tests. Tests for color, gloss, that again help us establish a base line for what is going on after we treat the objects.

Once we put this rust converter on top and have the rust react with the tannic acid or the phosphoric acid. And so once we’ve done that, then we stick it in an instrument called a QUV weatherometer, which is a fancy way of saying something that artificially weathers an object.

So instead of putting the metal outside for seven months, instead we’re going to put it in the QUV where its exposed alternately to UV light and then to a dark condensation cycle simulating what happens outside.

So we’re hoping that with our samples in the QUV, we’ll be able to chart how well these converters work over a long period of time. So we want to know, first of all, which one initially causes the most change to the rust, but then we also want to know which one is going to hold up the best over this whole period of time.

So we’re hoping that the testing in the QUV will help us chart that. And we have, the samples going in for a total of 8,000 hours, which sounds like a lot. But what’s going to happen actually is at different points we’re going to pull them out and run these documentation studies again.

Simple things like, making a measurement of the color and the gloss, but then also using the FTIR and the laser profiling system, and we’re hoping using these methods to be able to actually chart the rate of failure or the rate of success for each of the five different converters that we’re studying.

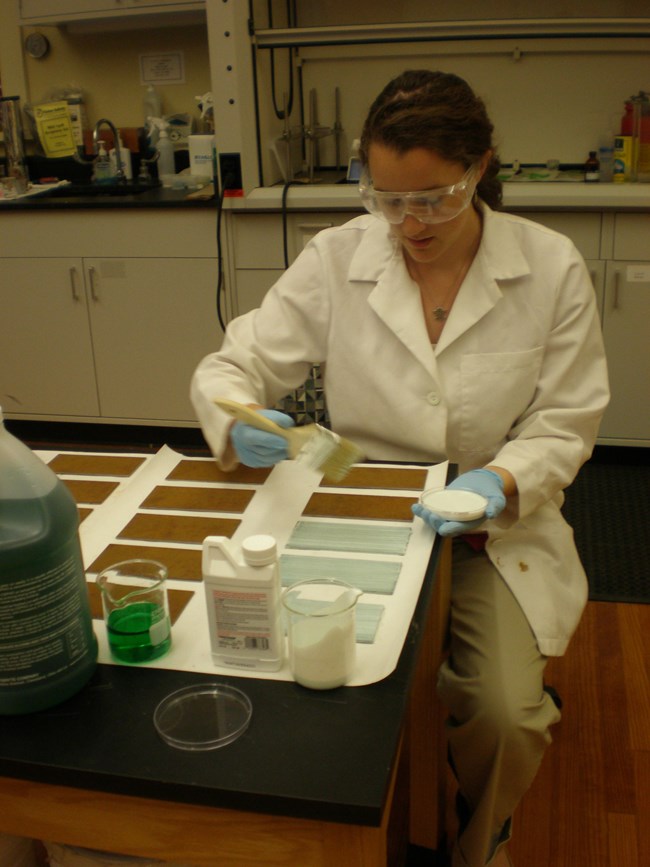

Caitlin Oshida is taking photos of preliminary testing samples.

This actually is a follow up of a study done by the Canadian Conservation Institute, way back in 1988, and at this point all of the converters that they studied aren’t commercially available. So you cant go to your local hardware store and pick up any of these. So we’re trying to update it.

We have some more advanced analytical techniques that we can use, but then we also have rust converters that you can go and pick up at Lowe’s or at Home Hardware or where ever. So we’re trying to do a different variety, but also things that will be available not just for me in a lab but for someone who may have a local museum or own a historic home or just have a rusty chair that they want to fix up.

Caitlin Oshida: Pesticides on Brick and Stone

Caitlin Oshida: Hi, my name is Caitlin Oshida, I’m from Fairfax, Va., and I graduated this past May from the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Va. This summer I’m going to be working with Dr. Mary Striegel and Debbie Smith on a project to determine the effects of herbicide on stone and masonry. So far we have conducted a survey that was sent out to all National Park Service facility managers and Integrated Pest Management facility managers and to collect data on what type of herbicide they use, how often they use it, the concentration they use, and some of the historic features that they have in their park or there site area that comes in contact with herbicide.

The survey just closed, and we got a number of results back, 98, which is very nice. So now I’m in the process of designing experimental design that will take the data that we have collected and make an experiment, so we can actually see if herbicide has any physical and chemical effects on different building material.

So far we know that we’re gonna use “Round-up“, about over 50 percent of the park services that we got responses from use Round-up. The second herbicide we’re going to use is Garlon 4. And we’re not sure if we’re going to use the third, but we would like to try to and see what different chemicals and their active ingredient is and what it can do to the building materials. The building materials we’ve decided to use are brick, concrete and limestone. We might do granite if we have time, but otherwise we’re just going to use those three.

My job this year is just to design the experiment and do preliminary research, this involves like small testing to see if we’ll actually get results. Hopefully, within the next year the experiment will be conducted by someone else, but unfortunately I will not be here for that.

But I look forward to seeing if my design works and see what the results are. The information that we’ll collect from this experiment will help not only historic sites, but day-to-day people in your community to protect their homes or their buildings or their features from herbicide and to know what the chemical effect is.

We know what the chemical effect of herbicide is on plants and ecological effects of that, but we’re unsure of the building materials. So this will help determine, if like, if they’re spraying herbicide near their house and their foundation. Whether the foundation is in danger of being destroyed or damaged, degraded in anyway.

So my next step in this is going to be to do preliminary testing, like I said before, and that involves submerging completely small samples, core samples of brick, limestone and concrete in Round-up completely to just make sure that we’re actually gonna get results and see some discoloration. This is going to be totally different from the actual experiment where it’s going to be more realistic. Its going to be a controlled spray every few hours as determined by my design plan.

National Park Service

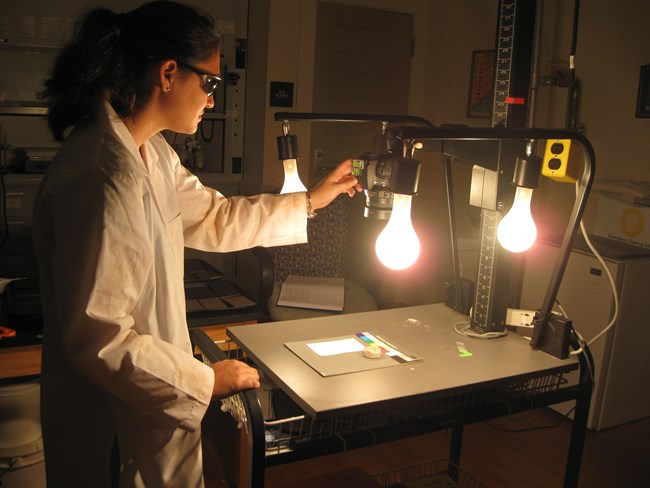

Kim Martin: Paint Remover Study

Kim Martin: Hi, I’m Kim Martin and I just graduated from Clemson University in South Carolina, and I just got here in Natchitoches. I’m working on the paint remover study. We gathered historic and modern bricks, and then we cored the bricks to make them into round samples so that they fit into all of our machines. The bricks were weighed and put under the colorimeter so that they got a number assigned to the exact color that they are. That way it’s more scientific when you go back and test again, you can tell the difference in the number.

A colorimeter is this machine that you sit on top of the brick, and it measures saturation and a bunch of other factors. And then it’s a computerized thing, and then it assigns you a number. So after all this initial information was gathered on the samples, some of the samples were painted others were left unpainted as controls. The samples have a couple of different layer categories so that you can tell if there’s more layers. This particular type of remover might work better for you if there’s less, maybe you can go with a less stringent one.

So right now the samples are in the QUV, it’s an artificial weathering machine. It puts them under ultraviolet light, it exposes them to condensation and heat and that process is just really so that we can weather the paint, so that you can see if a particular type of remover works better on weathered paint rather than new paint. New paint is often easier to remove than weathered paint, and then the goal I think of the study is just to see how different types of removers work on historic or modern brick. Because historic brick tends to be more porous. It’s softer. It’s not heated to the same type of level as a modern brick because of the technology at the time. So these different chemicals may leach in deeper, they might change the surface color or any of these things so we’re just trying to figure out what’s most appropriate.

Hopefully a person would walk away knowing what type of remover to use on their building, obviously you’ll have to asses whether you have historic or modern brick. But if you came in with that information you would know, this may be the most appropriate thing for you to use.

National Park Service

Landscape Maintenance Training Curriculum & Video

Stephanie Nelson: Hi, I’m Stephanie Nelson and I’m the historic landscapes intern. My projects are based on maintaining historic landscapes. I completed my undergraduate degree at Washington University in St. Louis, where I studied Environmental Studies and Spanish. I finished my degree of Master of Landscape Architecture at Louisiana State University this past spring and found my love for historic landscapes there.

This summer I will be working to find training items that people can use to learn how to maintain their historic landscapes, whether it be maintenance workers or individual home owners. Natchitoches is blessed with a whole bunch of old houses and old yards and older plants have different care requirements than newer ones. So hopefully through the video that I’ll be creating and other resources that we’ll be making available, home owners in Natchitoches will have better ideas and better be able to care for and prolong the life of their plants.

So far this summer, I’ve been working with the National Park Service offices to work to develop a maintenance training curriculum that can be taken by maintenance workers at historic sites so they can learn how to better take care of their landscapes. I’ve also been looking for different documents or videos, websites, publications that speak of how to care for historic landscapes. So those are kind of few and far between, so this work is really important so that people can preserve and prolong the life of their older plants instead of having to replace new ones. Especially historic trees, if you get rid of a live oak, it really changes a place. So there is a lot that can be done to keep a tree healthy, so that it can live longer so we will be presenting some of that information.

I’ll be presenting a training video for landscape maintenance workers at Preservation in Your Community. We are working with maintenance staff at Cane River Creole National Heritage Area to address some of their concerns. When new maintenance workers come on who may be more familiar with working in modern landscapes, there are some challenges that are presented when switching to working on a historic property. Like you need to be more sensitive of where you’re mowing to make sure that you don’t knock into historic buildings or damage trees because the older materials are a little weaker and it’s easier to do damage. So it’ll present information to new workers in those landscapes to educate them about why maintaining a cultural resource, like Oakland Plantation, requires different scales than like maintaining a corporate campus. So our hope is to have people become a little bit more sensitive and more knowledgeable about why things are done differently, and why they should take a little bit more time, like with mowing lawns, to protect whats there and help us keep great resources, like Oakland Plantation, looking as they are and having that historic feel and character to them.

At NCPTT, I’m learning a lot about historic landscapes and cultural landscapes, I didn’t have any formal training in it, so its a great opportunity for me to learn more about this branch of resource protection within the National Park Service and outside of it as well. So I hope to bring my background in studies in Louisiana to NCPTT to help more with local resources also. The South has a lot of unique plants and characteristics that aren’t found in the rest of the country, and so I hope to be able to bring some of that knowledge into NCPTT’s research and materials, and then also within the whole National Park Service.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.