Last updated: April 7, 2025

Article

Podcast 009: Digital Survey Methods in Archeology

The Portus Project

David Morgan: Welcome Graeme! What is The Portus Project?

Graeme Earl: The Portus Project is basically a collaboration between a whole bunch of people in the UK and in Italy and elsewhere, and it is a project mostly directed by Southampton University, the British School of Rome, and Cambridge, and we are looking at what’s the imperial port of Rome. It was probably the biggest classical fort of the first and second century.

David Morgan: What is the project’s focus and where do you stand in terms of its schedule?

Graeme Earl: What the project is focusing on is some excavation and site survey, looking also surveying the wider landscape and, from my perspective, looking at how various kinds of technology can be used to help on an ongoing excavation and survey project. The project has been running for over ten years in total because we have had a long series of geophysical seasons–we’ve done about two hundred and fifty hectares of geophysics on the site, and plus some marine geophysics. We have done some marine geophysics on the hexagonal basins as well, so pretty much every area anywhere near the site that isn’t underneath the modern airport we have done some geophysics.

David Morgan: What kinds of archeological materials are you finding?

Graeme Earl: I mean the artifact density is quite great, but it tends to be mostly things like quite workaday items, like building material. The area where we’re excavating is the industrial and commercial center, really, so you are looking at building materials: large lumps of masonry. You are not getting the fine, beautiful kinds of finds that we perhaps excavated in Egypt, where the preservation is so much better. You are getting an awful lot of materials though. The evidence that survives underground is fantastic, but there is also quite a lot surviving above ground. The scale of it is quite difficult to appreciate, but you are looking at warehouses that are maybe a couple of hundred meters long and fifty meters wide. It’s all big stuff, so it is quite a challenge for us working there.

David Morgan: What does it mean for an archeological record to be “born digital” and how does that apply to the Portus Project?

The Portus Project

Graeme Earl: Born digital in archeological terms normally relates to capturing data on site, as you say, in a digital fashion not using a conventional context sheet, not using conventional methods for planning and drawing up surveys and so on. At Portus we are experimenting with a lot of these techniques to create a born digital record, but what we are also able to do is to try and see how they relate to more conventional approaches. Is it better to have someone sat there with a computer and a wireless network and typing in context information, or typing in their geophysics grid location data straightaway? Or is it actually better to have somebody entering data on a piece of paper…on the back of a notebook–however they want to do it–and then afterwards bring the data together and put it in some kind of digital archive. We’ve got to end up with a digital record. At Portus we’re trying to whether actually using a born digital record helps at all in all aspects of archeological practice. I think the jury is still out on that.

David Morgan: How have archeologists adapted to creating born digital data?

Graeme Earl: It comes down to familiarity, really. If you are familiar with using a trowel and a pencil and a piece of permatrace then that’s a kind of place where you think about the archeology that you are doing. If you are really familiar with using a mouse or, I don’t know, some kind of VR equipment, or whatever –some technological process– if that is where you are most familiar, then that’s where your archeological engagement happens. That is where your interpretations derive from. The problems occur when you have someone who is very familiar with the computing, who is not so experienced , maybe, with the tactile excavation process, or vice versa, but if you are not familiar–if the computer is something that worries you–that you feel is falsely objectifying your data, for example, then it is not going to be a good thing to think with. It’s not going to be a good way of re-excavating the data.

The Portus Project

David Morgan: What technologies have the greatest potential to yield more digital data?

Graeme Earl: Technologies that require the least change in the way that you practice. So you use something that the excavator is familiar with–the camera–bolt on a few gizmos–exciting, flashing, and whizzing things–and then you produce some new useful archeological record at the end of it.

David Morgan: What are these PTMs and how are they used?

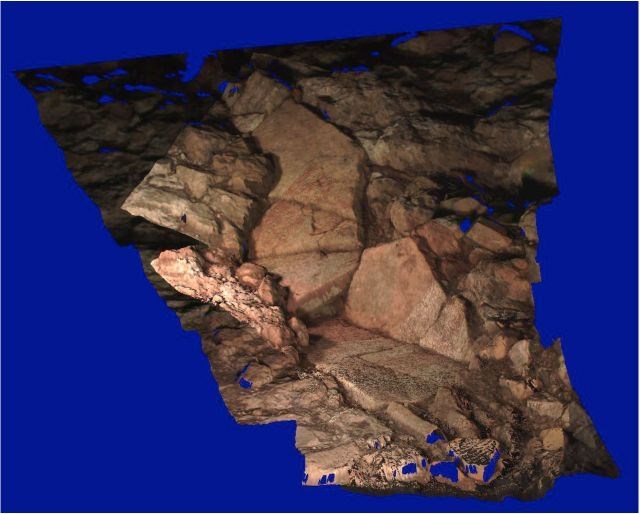

Graeme Earl: Polynomial Texture Maps, or PTMs, are a technology that was invented by a guy called Tom Malzbender at Hewlett Packard Labs. If you are familiar with recording something like rock art panels, or if you are working with inscriptions, which is a good example from over here, what you do when you are taking that photograph is you try and get the best light. You try to get the best raking lights so you can see the details. What PTMs are, really, is a way of capturing that variability in light and shade.

The Portus Project

Graeme Earl: A few of us in archeology have started to use this particular technique. So, there is Cultural Heritage Imaging over there in the States–you’ve been pretty much key players in it–and ourselves, trying to use it as an embedded practice within an archeological project. So as well as using it to record maybe something that is in a museum collection, or some rock art, we wanted to try and use it as a technique that was used day in and day out, just as a standard part of the post-excavation process.

I mean, one of the greatest things about the technology–you know, if you come to write a text and you want to produce a static image–you set up your virtual lights within the PTM, freeze the image, and there you’ve got just a perfectly composed finds image. You can tell people that it is amazing what they can do with a camera, a flashlight, and a shiny ball.

David Morgan: What is “virtual reality” and how do you use it in archeology?

Graeme Earl: If you want to be specific about what virtual reality is, virtual reality implies a kind of computer graphic model that you can interact with. There are lots of different terms for what this is: there is “virtual archeology,” there is “virtual reality archeology,” and there is to say “computer graphic imagery.” There is a whole host of them, but basically we’re just talking about methods primarily drawn from the film industry, and the things that makes Gladiator look beautiful, and using those kinds of technologies. Computer graphic models provide a really intuitive, quick way to convey what a really complicated interpretive process is.

David Morgan: Is there a danger inherent in the “Disneyfication” of cultural heritage?

Graeme Earl: That’s an interesting term. I would say I really don’t have any problem at all with the Disneyfication–the popularization–of cultural heritage. I think that the more people we can reach out to, and demonstrate to, the magic of Portus, or the magic of the archeology of Louisiana, the better. The more we can convey our own excitement for the discipline, which we’ve developed over however many years…if we have a chance to demonstrate or pass on that kind of excitement through maybe quite a simplified, exciting presentation, then that’s great. I think the more we do that, the more people would care about cultural heritage, and fewer bad things would happen to cultural heritage.

The Portus Project

Graeme Earl: That doesn’t mean that we give people carte blanche to lie about the past and to present a past as if we know all of the facts, but I don’t think that you have to have a very bland, sterile presentation of the past in order to be true to your archeological principles. I think you can convey the magic and the interpretation and the flamboyance of some of the practices, as well as being true to the archeology. And I think we’ll have a lot to gain in partnerships with people like Disney or Pixar–people who know how to tell these kinds of stories. We know about the past, and if we work together we’ll be presenting better stories.

David Morgan: One of the biggest problems with virtual interpretation is missing information. How do you handle missing data?

Graeme Earl: We are very good at taking portions of information and looking up all of the other correlating data sources: things that maybe better preserved at other sites–mixing and matching but doing it in a consistent fashion, and then bringing it together to form one, or preferably a series, of interpretations. So again I don’t think the production of computer graphic models differs from any other kind of aspect of the archeological process. Again, it is incumbent upon us to be true to the data as much as we can, and to make sure the representation of the archeology is as near as possible–as close to the truth–as we understand it. I don’t think you can use technology as a way to make it any clearer what data there really are. I think we’ve been maybe a little bit too worried in the past about computer images being overly convincing or computer representations being overly kind of scientific. I think we can take a step back and say: people who are looking at these–they know all about Pixar, they know that you can make things up, but they have to trust us that we archeologists aren’t in the business of making up, but interpreting.

David Morgan: What are some of the biggest problems with the adoption of some of these new technologies?

Graeme Earl: A practical problem…a practical consideration comes down to cost and various ways of measuring it. You don’t have to have ludicrous computers. You don’t have to have very expensive software. But, to a degree the better software that you have, the more computers that you have to produce the work, the more time you have, the more person-hours you have to dedicate to the project, the better the results that you are going to get. So there is always some kind of cost implication, and computer graphics in particular is very processor intensive. The bigger the computer you have, the better the results you have quicker, so that is always a limitation.

Graeme Earl: So the great thing is the more data you get like that now–so if you get your XRF data–because the computer graphics technologies enable you to represent all of that data in a physically accurate way, you know that when you look at the image it definitely isn’t just a pretty picture, because it’s based on a simulation of the interaction between light, pigment, the surface of the marble, deeper down…the subsurface scattering within the marble. The computer graphics now are at a stage where for the first time you know that it is physically right. It doesn’t just look right, it is just physically right. The example I use is look at Shrek 1, 2, and 3, and look at Shrek’s skin. Shrek’s skin in 3…if there is a real ogre in the world, then it would look exactly like Shrek.

David Morgan: Thanks very much for joining us today Graeme.

Read other Preservation Technology Podcast articles or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.