Last updated: August 24, 2022

Article

Places of "Temporary" Buildings: WWII's 700 and 800 Series Buildings

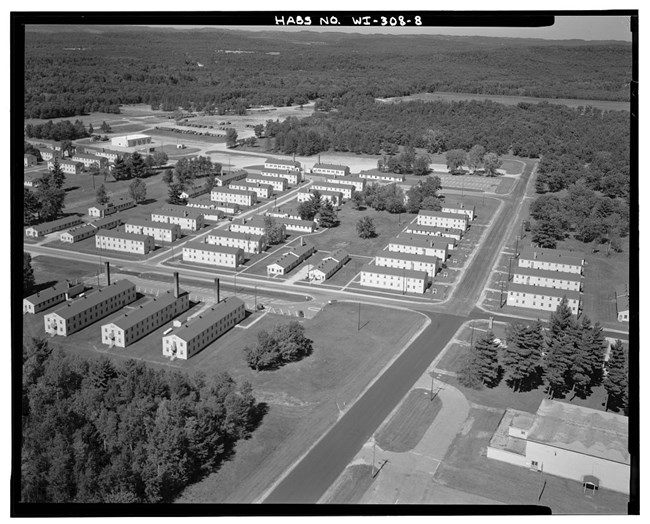

Photo by Martin Stupich, Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Even before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the United States began mobilizing the nation towards another world war. The Selective Training and Service Act was enacted on September 16, 1940. Shortly after, men began to report for military duty across the nation. Army officials knew that their peacetime infrastructure would not be able to house all the new troops. To accommodate these incoming troops, thousands of new buildings needed to be built quickly.

By the 1940s, living standards across the United States had risen. Access to indoor plumbing, electricity, and central heating was no longer a luxury—it was becoming the standard. Military housing needed to reflect this. The Selective Service Training and Service Act of 1940 declared that no one could be sworn into service unless the government was able to provide them with care “essential to public and personal health.” President Franklin Roosevelt himself stated, “I can give assurance to the mothers and fathers of America that each and every one of their boys in training will be well housed.”[1]

The first standardized plans for military cantonments (camps) used during World War II were called 700 Series plans. The Quartermaster Corps originally designed these plans in 1928. The most common use for 700 Series plans were barracks, but builders could adjust the designs to fit many other purposes. The buildings were simple enough that they did not need skilled workers to assemble, but still possessed modern amenities. Using these standardized plans, prefabricated components, locally-sourced materials, and an efficient construction style, entire buildings could be raised in a matter of hours. 800 Series plans followed shortly after, with updates and fixes for the 700 Series’ design flaws. Around 30,000 of these buildings were built between 1940 and 1945.[2]

After the war, many buildings retained their wartime uses. Some were demolished. Others were moved and took on a new use. The plain wood buildings were ideal for farmers, and some buildings became barns and equipment sheds. Although called “temporary” buildings, many remained standing for decades after the war. Some can still be seen even today.

Below are examples of 700 and 800 Series buildings built for World War II mobilization. These selections exemplify the simplicity, diversity, and durability of these “temporary” buildings. Most of these examples have been surveyed by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS). HABS documentation provides structure drawings, photographs, and written histories. These documents allow us to study these buildings even if they are modified or demolished.[3]

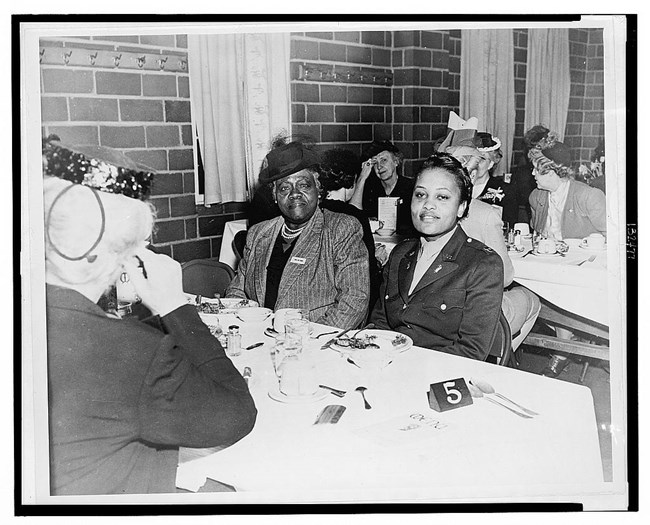

Photo by Martin Stupich, Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Historic American Buildings Survey. Public domain.

1. Barracks, Camp Edwards: Bourne, MA

Camp Edwards was the first mobilization project that used 700 Series building plans. Here, camp builders tested the plan's methods and efficiency. Between September and December 1940, 471 700 Series buildings were built on these grounds. The plans were so successful that camp planners sent copies to 50 other developing military installations. Building T-1310 was one of many buildings designated as barracks. Like most of the temporary buildings, it was completed around the end of 1940.

Building T-1310 was a model 700 Series barracks. It had two floors containing living quarters and an attached lavatory. Sixty-three men could live in this barracks. Enlisted men lived in the open bay area, and noncommissioned officers lived in two small bedrooms on each floor. 700 Series plans contained an architectural feature called an “aqua media,” which was an overhang above the first floor windows. Aqua medias allowed windows to be left open for fresh air, even if it was raining outside. Although they seemed like a good idea, squa medias were not effective in blowing rain. The Quartermaster Corps discontinued them in updated 700 Series and 800 Series plans.

Camp Edwards is still an active military training center. Many of its World War II temporary buildings still exist, including Building T-1310. It was surveyed by HABS in 1990.

Photo by the US Military. Courtesy of the Fort Huachuca Museum.

2. Mountain View Officers’ Club, Fort Huachuca: Sierra Vista, AZ

Fort Huachuca underwent rapid expansion in 1942, building around 1,400 temporary structures. At the time, Fort Huachuca was the largest training site for African American soldiers. The armed forces were not desegregated until 1948, so separate buildings were built for Black soldiers. The Mountain View Officers’ Club served the African American officers on the base. The 700 Series building opened on Labor Day Weekend in 1942.

The Mountain View Officers’ Club quickly became the center of entertainment for Black troops stationed at the fort. It hosted dinners, weddings, dances, and other cultural events throughout the war. The most notable event held at the club was an art exhibition for African American artists in 1943. Thirty-seven African American artists exhibited their work to an integrated crowd of military officials and civilians. Among the artwork was a mural painted by Charles White entitled Progress of the American Negro (Five Great American Negroes). The mural remained in the building throughout the war. In 1947, it was moved to Howard University in Washington, DC. It can now be viewed in the Reading Room of the Vernon E. Jordan, Jr., Esq. Law Library, at the Howard University School of Law.

This building is one of two remaining officers' clubs used by African American officers in the United States.[4] The National Trust for Historic Preservation named it one of America's 11 Most Endangered Places in 2013. The Mountain View Officers’ Club was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on January 24, 2017. Fort Huachuca was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 20, 1974, and became a National Historic Landmark on May 11, 1976.

3. Base Chapel, Mountain Home Air Force Base: Mountain Home, ID

Mountain Home Army Air Field was built between 1942 and 1943 as a bomber training base. Out of the 343 buildings built, Building 611 was the only chapel built. This 800 Series building was completed on August 3, 1943.

The dedicated building of a chapel shows shifting ideas for how a nation’s army should be treated. Soldiers could have easily used a club or recreation hall for worship, but people thought soldiers’ morale would be higher if they had a special building for worship. The 800 Series building plan was slightly modified to allow for a steeple and cross, and the building had pews, a lectern, and an altar rail. Building 611 was only one story, and included a loft for a choir. To appear more like a church, Building 611 used a laminated arch system instead of a more typically-seen truss system.

Left image

Exterior of the church.

Credit: Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

Right image

Interior of the church, showing the laminated arch system.

Credit: Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

In 1948, Mountain Home Army Air Field became Mountain Home Air Force Base. Today, Building 611 has moved from its original spot to a nearby location. It has been remodeled several times, but still retains much of its historical and architectural integrity. Now called Liberty Chapel, the building retains the same purpose as when it was built in 1943—serving as a place of worship for the residents of the base. Building 611 was surveyed by HABS in 1996.

Photo by Bill Lebovich, Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

4. WAC Barracks, Fitzsimons General Hospital: Aurora, CO

In 1943, the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) became the Women’s Army Corps (WAC).[5] At Fitzsimons General Hospital, WACs served as medical technicians, physical therapists, optometrists, and many other skilled positions. In anticipation of receiving WACs to care for returning soldiers, Fitzsimons built several WAC barracks in 1944, including Building 131.

WAC barracks were different from typical 700 or 800 Series barracks. The US Army developed special standards for WAC barracks in 1943, stating: “standards for housing the Women's Army Corps sohould be higher than those for the housing of male personnel, with additional changes where differences between men and women necessitated such changes and adjustment.”[6] Some adjustments were due to safety concerns. Women’s barracks were required to be at least fifty yards away from the nearest men’s barracks. WAC barracks also had a staircase fire escape instead of a ladder, because the WAC uniform skirt made it difficult to climb down a ladder. Other adjustments included adding bathtubs, bathroom partitions, ironing boards, window curtains, extra luggage space, and one beauty parlor per company grouping. Some WACs turned the noncommissioned officer’s quarters in their barracks into dayrooms where they could either relax or host dates.

Fitzsimons General Hospital is now the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. Building 131 was surveyed by HABS in 1995 and was demolished shortly after.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

5. Mess Hall, Fort Des Moines: Des Moines, IA

Fort Des Moines boasts a significant role in WWI as a training center for African American officers, and it was reactivated for World War II. In 1942, Fort Des Moines was selected as a Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) training center. Shortly after, it expanded to accommodate the incoming troops. During the war, the fort was known as “West Point for Women,” and was the only training facility for WAAC officers in the country. Building 106 was built during this expansion and served as a mess hall. This 800 Series building was completed on September 15, 1942.

Located between two officers' barracks, Building 106 served during the war as the officers’ mess hall. It had a capacity of 172 people. The building had an open area dining center, with separate rooms for the kitchen and storage areas. WACs often decorated their mess halls, and treated the building as another center of entertainment. Building 106 and other temporary buildings built at Fort Des Moines were made of brick and tile instead of wood. This was because the US Army required WAAC facilities to be higher quality than regular Army buildings.

Today, developers have readapted Fort Des Moines for several uses, including housing and a museum. Building 106 was surveyed by HABS in 2017, and it now serves as a gym. Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School was added to the National Register of Historic Places and became a National Historic Landmark on May 30, 1974.

Photo by Dewey Livingston, Historic American Buildings Survey. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. Public domain.

6. Theater, Fort Barry: Sausalito, CA

Fort Barry in the San Francisco Bay was central to defending California’s coastline in the event of an aerial or seaborne attack. To prepare for World War II, the military modernized the fort. Building FA-946 was one of several theaters built during this time to serve the many troops stationed in the San Francisco Bay area. The 700 Series building was completed on April 22, 1941.

The building of a dedicated theater building reflects the cost and resources that the Army spared to make soldiers feel more at home. Building FA-946 was a single-story building that held 1,038 seats. It contained an entrance and projector room, the main theater room, and a backstage area for performers. During the war, this theater served as an entertainment center for troops at Forts Barry, Baker, and Cronkite. In addition to film screenings, celebrity performances took place here. Bob Hope, Pat O’Brien and other celebrities entertained troops during World War II.

In 1974, the ownership of Fort Barry was transferred from the US Army to the National Park Service. This theater was demolished in the early 1980s, but a nearly identical theater exists at the nearby Presidio of San Francisco. The National Park Service decided that Building FA-947 could be demolished because the Presidio’s theater was being preserved. Before its demolishment, Building FA-946 was surveyed by HABS. Fort Barry was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 12, 1973, and the theater was a contributing building. Fort Barry is located within Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

The content for this article was researched and written by Hannah Haack, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education and the Park History Program.

[1] Perry Bush and Diane Shaw Wasch, World War II and the U.S. Army Mobilization Program: A History of 700 and 800 Series Cantonment Construction (Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 1992), 11.

[2] In addition to the 700 and 800 Series Plans, the military built other prefabricated structure types. One of the most common was the Quonset hut, a lightweight steel building that could serve many purposes.

[3] For more examples of this building type, search for “700 Series” or “800 Series” within the Historic American Buildings Survey Collection at the Library of Congress.

[4] The other club is located at Fort Leonard Wood, MO.

[5] To learn more about WACs, check out this article about the 67th Women's Army Auxillary Corps.

[6] Bush and Wasch, World War II and the U.S. Army Mobilization Program, 22.

Cole, Alexandra C. “Mountain Home Air Force Base, Base Chapel.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1995. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. ID-118-A). Accessed July 29, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/id/id0200/id0289/data/id0289data.pdf.

Collins, William and Jennifer Levstik. “Mountain View Officers’ Club.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2017).

“Fitzsimons General Hospital, W.A.C. Barracks.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1995. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. CO-172-Q). Accessed July 29, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/co/co0400/co0492/data/co0492data.pdf.

“Fitzsimons General Hospital.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1995. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. CO-172). Accessed July 29, 2022. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/co/co0300/co0346/data/co0346data.pdf.

Greenlee, Marcia M., Nancy Witherell, and Suzanne Evans. “Fort Des Moines Provisional Army Officer Training School.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/75338177.

Landreth, Keith, Richard Hayes, Daniel R. Lapp, James Bowman, and Steve Turner. “Camp Edwards, Building T-1310.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1990. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. MA-1249-H). Accessed July 29, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ma/ma1400/ma1498/data/ma1498data.pdf.

Lile, Thomas. “Forts Baker, Barry, and Cronkhite.” National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1973). https://catalog.archives.gov/id/123859676.

Mangum, Rachael, and Susan Bupp. “Fort Des Moines Historic Complex, Building No. 106.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. IA-121-AF). Accessed July 29, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ia/ia0500/ia0548/data/ia0548data.pdf.

“Mountain View Black Officers’ Club.” Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://preservetucson.org/stories/mountain-view-black-officers-club/.

“Mountain View Officers' Club at Fort Huachuca: National Trust for Historic Preservation.” Mountain View Officers' Club at Fort Huachuca | National Trust for Historic Preservation. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://savingplaces.org/places/mountain-view-officers-club-at-fort-huachuca.

Scolari, Paul. “Fort Barry, Theater.” Written Historical and Descriptive Data, Historic American Buildings Survey, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1980. From Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress (HABS No. CA-2642-A). Accessed August 1, 2022.

https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/master/pnp/habshaer/ca/ca2100/ca2186/data/ca2186data.pdf.

Treadwell, Mattie E. The Women's Army Corps. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1991.

Wasch, Diane Shaw, Perry Bush, Keith Landreth, James Glass, et. al. World War II and the U.S. Army Mobilization Program: A History of 700 and 800 Series Cantonment Construction. Edited by Arlene R. Kriv. Washington, DC: Department of the Interior, 1992.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- military history

- us army

- us air force

- african american history

- black history

- women's history

- women in the military

- wac

- waac

- architecture

- architectural history

- historic american buildings survey

- habs

- historic preservation

- preservation

- massachusetts

- california

- colorado

- iowa

- idaho

- arizona

- places of article

- places of...