Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Black Women Mathematicians in Aeronautics.

Article

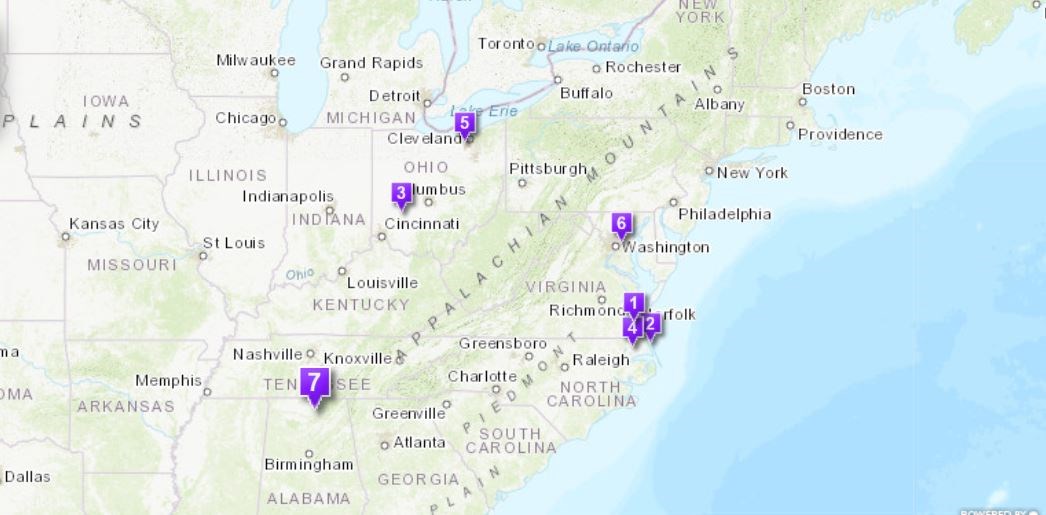

Places of Hidden Figures: Black Women Mathematicians in Aeronautics and the Space Race

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

In 2016, the film Hidden Figures skyrocketed Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan to household names. During the 1950s and 1960s, they joined dozens of other African American women who crunched numbers and processed data for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and its successor, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Many of these women got their start as “human computers,” performing complicated calculations that supported the work of male engineers. NACA began hiring white women as computers in 1935. The agency did not open these positions to African American women until 1943 to address labor shortages during World War II. At the time, opportunities for women to advance in their careers were limited. African American women faced additional barriers because of racial discrimination.

Nevertheless, African American women played a critical role in the Space Race and rose to new heights as mathematicians, computer programmers, team project leads, and engineers at NASA. This article features properties in the National Register of Historic Places that are related to their stories.

1. NASA Langley Research Center Historic District (Katherine Johnson)

When Katherine Johnson began her 33-year career in 1953, Langley Research Center was racially segregated. For her first two weeks, Johnson worked in the all-African American West Area Computing section. She was quickly reassigned to the Maneuver Loads Branch of the Flight Research Division. This assignment led to some of the achievements for which Johnson is best known. In 1961, she analyzed the flight trajectory for Alan Shepard’s Freedom 7 mission, the first human spaceflight completed by the United States. The next year, Johnson also verified an electronic computer’s calculations for the Friendship 7 mission. During this mission, John Glenn became the first American to orbit Earth. During the 1960s, her math also helped Project Apollo to send astronauts to the moon and make the moon landings a reality. Johnson considered her contributions to Project Apollo as her greatest achievement.

NASA Langley Research Center Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2012.

2. Hampton City Hall (Mary W. Jackson)

After starting at NACA in 1951, Mary W. Jackson worked as a West Area computer for two years. Because of her mathematical skill, engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki invited Jackson to join his team working on the Supersonic Pressure Tunnel. Jackson gained lots of hands-on experience in this role, but she had bigger dreams: to become an engineer herself. Czarnecki suggested that she enroll in a special training program to transition from a mathematician to an engineer. Although the University of Virginia ran the program, classes were held at Hampton High School. Because the school was segregated, the City of Hampton had to approve Jackson’s participation in the program. When Jackson appeared before a judge at Hampton City Hall to make her case, she was approved for enrollment. After completing the necessary courses, Jackson became the first African American woman engineer at NASA in 1958. That year, she also published her first report, “Effects of Nose Angle and Mach Number on Transition Cones at Supersonic Speeds,” with Czarnecki.

Hampton City Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2007.

3. Wilberforce University (Dorothy Vaughan)

When she was 15 years old, Dorothy Vaughan received a full tuition scholarship to study at Wilberforce University, the first private historically Black college. Vaughan majored in mathematics and French. Her professors recommended that she pursue further graduate study at Howard University. Vaughan declined and took a job in the West Area Computing unit at Langley Research campus in 1943. For years, Vaughan was passed over for promotions despite her skills as a mathematician. Nevertheless, she continued to pursue a title worthy of her experience and skillset. She finally succeeded in 1949, becoming the first African American woman manager at NACA. During her career, she oversaw both Katherine Johnson and Mary Jackson. When NACA became NASA in 1958, the agency began to eliminate segregated facilities, including West Computing. Vaughan and many other computers took new jobs in the Analysis and Computation Division, which was not segregated by race or gender. In that role, Vaughan blazed a trail, mastering the newest electronic computer programming technologies. She worked at NASA until her retirement in 1971.

Wilberforce University was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2004.

4. Hampton Institute (Christine Darden)

Christine Darden graduated from Hampton Institute with her bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1958. She briefly taught high school math before earning her master’s degree in applied mathematics at Virginia State College. Darden began working as a computer at NASA Langley Research Center in 1967. Although the agency began to desegregate its facilities in 1958, she still experienced discrimination. After working at NASA for 8 years without a promotion, Darden finally confronted a supervisor. She asked why the agency hired men who shared her educational background as engineers but did not offer her the same opportunities. The supervisor could not dispute Darden’s point and transferred her to the engineering section. After Darden began her career as an engineer, she spent the next 25 years pioneering sonic boom minimization and researching aerodynamics and supersonic flight. In 1983, she earned her doctorate in mechanical engineering from The George Washington University.

Hampton Institute was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

Public Domain.

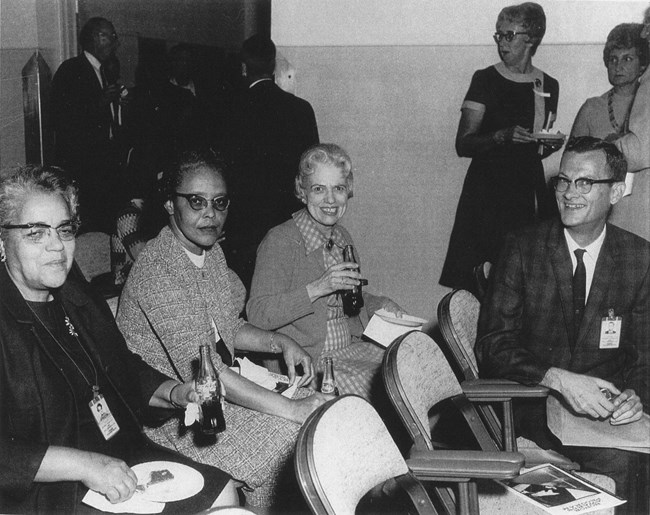

5. NASA Lewis Research Center–Development Engineering Building & Annex (Annie Easley)

When Annie Easley started working at NACA in 1955, she was one of four African Americans among 2,500 employees. She decided to apply after reading in the newspaper about two sisters who worked there as computers. Over the course of her 34-year career, Easley worked as computer scientist, mathematician, and rocket scientist at Lewis (Glenn) Research Center in Cleveland, Ohio. She became a leader on the team that developed software for the Centaur Upper Stage Rocket. The Centaur was a booster with a high-energy propellant, powerful enough to launch satellites and probes into orbit and beyond. Easley was committed to increasing diversity at NASA. She attended college career days and encouraged women and people of color to consider fields in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). She also became an Equal Employment Opportunity counselor and ensured NASA followed through on discrimination complaints.

NASA Lewis Research Center–Development Engineering Building & Annex was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

Photo courtesy NASA, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6452800

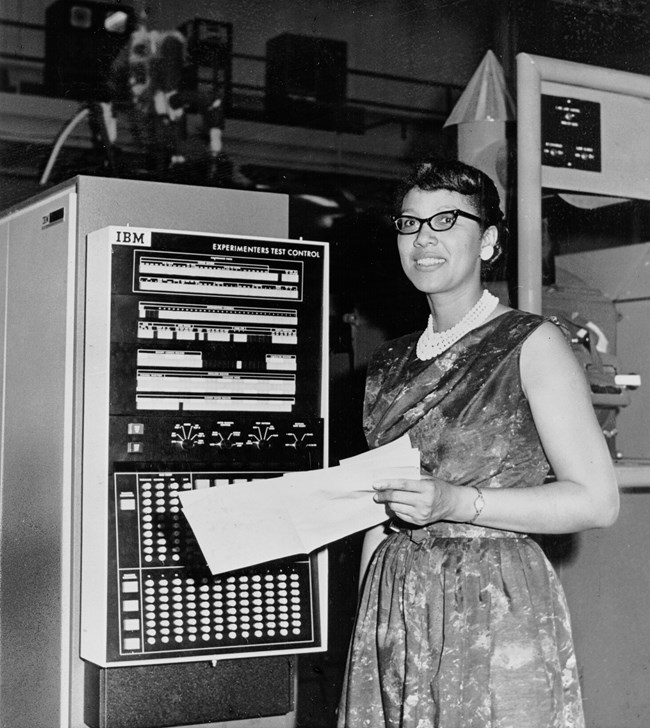

6. Spacecraft Magnetic Test Facility at Goddard Space Flight Center (Melba Roy Mouton)

After earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics from Howard University, Melba Roy Mouton spent several years working for the Army Map Service and the U.S. Census Bureau. In 1959, Mouton began working at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. At Goddard, Mouton led the group of human computers who tracked the Echo Satellites 1 and 2. The calculations that they performed enabled NASA to predict the flight paths and locations of spacecraft in Earth’s orbit. Due to the gravitational pull of other planets, the moon, and Earth, this was a difficult task even for an electronic computer. During her 18 years at Goddard, Mouton served in several leadership roles in the computer programming, data systems, trajectory analysis, and research divisions.

The Spacecraft Magnetic Test Facility at Goddard Space Flight Center was added to the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985.

7. Propulsion and Structural Test Facility at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (Jeanette A. Scissum)

Jeanette A. Scissum received her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mathematics from Alabama A & M University. In 1964, she began her career at the Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. At Marshall, Scissum produced a report about magnetic activity on the surface of the sun. This report helped to improve how NASA predicted cyclical changes in solar activity. Scissum later worked in Marshall’s the Space Environment Branch and contributed to the Atmospheric, Magnetospheric, and Plasmas in Space project. She also volunteered as an Equal Opportunity officer.

The Propulsion and Structural Test Facility at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.

Selected Sources

“Goddard’s Own ‘Hidden Figure,’ and a Legend of Invention.” Goddard View 13, no. 1 (January 2017): 9. Accessed February 3, 2021. https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/atoms/files/goddardviewv13i1online.pdf.

Mills, Anne K. “Annie Easley, Computer Scientist.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Edited by Kelly Heidman. Last modified August 7, 2017. https://www.nasa.gov/feature/annie-easley-computer-scientist.

Mohon, Lee. “Jeanette A. Scissum, Scientist and Mathematician at NASA Marshall.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Last modified March 7, 2019. https://www.nasa.gov/centers/marshall/history/jeanette-scissum-3.html.

Shetterly, Margot Lee. Hidden Figures: The Untold True Story of Four African-American Women who Helped Launch Our Nation Into Space. New York: William Morrow and Company, 2016.

Smith, Yvette, ed. “Christine Darden: From Human Computer to Engineer.” National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Last modified February 27, 2020. https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/christine-darden-from-human-computer-to-engineer.

Tags

- women's history

- civil rights

- african american history

- african american women

- space

- space science

- women's rights

- science

- science and technology

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- virginia

- virginia history

- ohio

- ohio history

- maryland

- maryland history

- huntsville

- alabama

- alabama history

- women in science and technology

- places of...

- places of article

- teaching with historic places

- twhplp