Last updated: March 12, 2025

Article

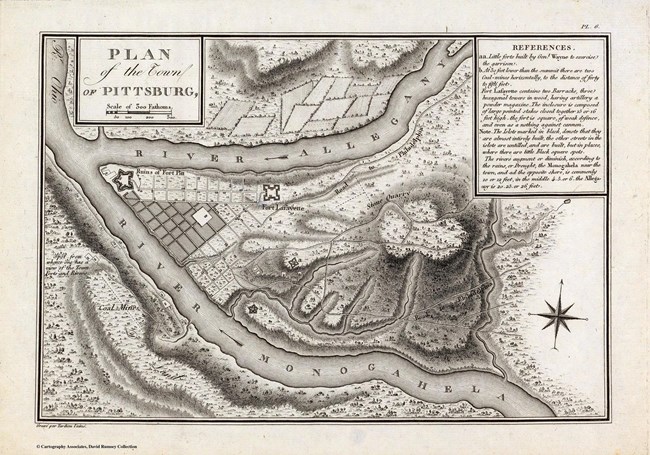

Pittsburgh in 1803

George Henri Victor Collot, David Rumsey Map Collection

Pittsburgh may seem far from New Orleans, but the two towns were closely connected via the Mississippi watershed. Trade items went up and down the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, connecting Spanish, French, and American territories. The Missouri River, which Meriwether Lewis and William Clark would take all the way to its headwaters in present-day Montana, also connected into this same riverine system.

The Ohio River Valley had, for millennia, been a travel corridor for Indigenous people seeking refuge from expanding empires of Britain, France, and eventually, the United States. Delaware, Shawnee, Wyandot, Huron, Mahican, and Haudenosaunee people had moved down the Ohio in search of places to live away from these land-hungry new arrivals.

Following the American Revolutionary War, even more settlers moved farther west.

By 1800, Pittsburgh had a population of 2,400, growing to nearly 5,000 by 1810. Boat building was the city’s most important industry: ample woods nearby were filled with trees with the right kinds of toughness and rot-resistance to build strong and long-lasting boats. Other industries started by American settlers included iron works, grist mills, salt works, powder works, sawmills, oil mills, paper mill, glassworks, and breweries.

By 1803, Indigenous people of many different cultures and backgrounds, American settlers, French traders, and Spanish settlers and traders all lived within this massive watershed. This was the year that France sold to the United States the vast tract of land they “controlled” between the Mississippi River and the Continental Divide, in the Rocky Mountains—land that Indigenous people have lived on since time immemorial.

When Lewis left Pittsburgh, he was not heading to a vast, unpopulated wilderness. He was traveling into heavily populated areas that were and had been the home of Indigenous people for millennia.

About this article: This article is part of a series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”