Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 15, No. 1, Spring 2023.

Article

Petrified Forest Brings the Funk with the World’s Oldest Fossil Caecilian

Dr. Adam Marsh, Lead Paleontologist

Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona

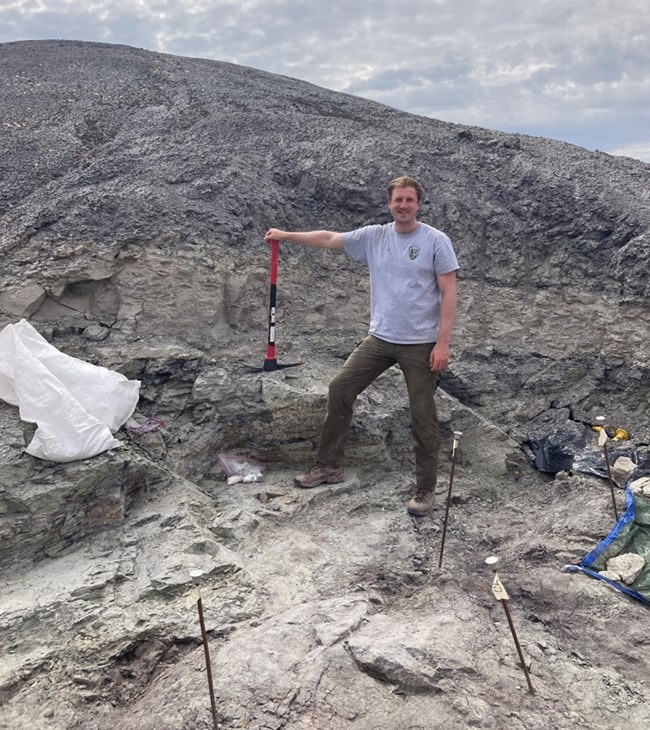

PEFO paleontology volunteer interns Will Reyes (PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin, front left) and Elliott Armour Smith (PhD student at the University of Washington, front right), and PEFO lead paleontologist Dr. Adam Marsh (back) working to expose fossil bones and collecting matrix at PFV 456 in 2021.

Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO) is home to a diverse amphibian fauna, most of which can easily be seen at night on the park road after a heavy monsoon rainfall, including six species of toad and the tiger salamander. Modern amphibians across the globe include frogs and toads, salamanders and newts, and caecilians. There are more than 200 species of caecilians that live in the tropical regions of Central and South America, Africa, and southeastern Asia (Wilkinson et al., 2011). Caecilians are limbless, tubular amphibians that often lack eyes and have a blunt snout, a double row of teeth in the upper and lower jaws, and a unique chemosensory tentacular organ that protrudes from the side of the face. Most caecilians are burrowing animals, but there are some fully aquatic species. Many caecilians give birth to live young that have special teeth to feed on a nutritious lining secreted in the mother’s oviduct, and those species that hatch from eggs eat a nutritious layer of skin from the mother (Wilkinson et al., 2008). They are without a doubt one of the strangest and most fascinating animal groups which most North Americans have never heard of.

Amphibians were also present in subtropical, equatorial PEFO 220 million years ago during the Late Triassic Period, most notably the Volkswagen-sized metoposaur Anaschisma browni (Gee et al., 2019) and the continent’s earliest frogs (Stocker et al., 2019), establishing an ecological and evolutionary link between the past and present at Petrified Forest. However, the evolutionary relationships between living and long-extinct amphibian groups have been very difficult to determine, partly due to convergent evolution but mostly due to the sparse fossil record of early-diverging members of modern amphibian groups. This has led to numerous hypotheses, including one that suggests that frogs and salamanders are closely related to one another as temnospondyls but caecilians are more closely related to an extinct group called the lepospondyls (Anderson et al., 2008). Only ten fossil caecilian specimens have previously been reported from the Cretaceous and Paleocene of northern Africa (Evans and Sigogneau-Russell, 2001) and the Early Jurassic of the Navajo Nation (Jenkins and Walsh, 1993). However, DNA studies of modern amphibians suggests an 87 million-year ghost lineage extending back to the late Carboniferous or early Permian (San Mauro, 2010), begging the question, “Where are the Triassic caecilians?”.

That question has been answered over the course of several years of research at PEFO, led by Ben Kligman (seasonal paleontologist and PhD candidate at Virginia Tech) and Dr. Adam Marsh (lead paleontologist), culminating in the publication of one of Kligman’s dissertation chapters in the prestigious scientific journal Nature: "Triassic stem caecilian supports dissorophoid origin of living amphibians" (Kligman et al., 2023). In this article, PEFO paleontologists and colleagues (all of which were either PEFO interns or staff or have otherwise worked at PEFO since 2001) introduce the world’s oldest caecilian, Funcusvermis gilmorei, from the Chinle Formation approximately 220 million years ago, extending the fossil record back in time another 35 million years from the previously oldest caecilian. Represented by more than 80 right lower jaws, Funcusvermis gilmorei multiplies the total known caecilian fossils worldwide by eightfold. It has the double row of teeth in the upper and lower jaws unique to caecilians, but it also has transitional anatomy found in earlier amphibians but not in living caecilians, including hindlimbs and the lack of a tentacular organ. Funcusvermis is Latin for “Funky Worm”, a 1972 hit song by the funk band the Ohio Players, a song that was played every day in the field in 2019 and 2021 as good luck to find more caecilians. The species name honors Kligman’s early mentor Ned Gilmore, the collections manager at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia. The three-dimensionally-preserved elements of Funcusvermis help to support the hypothesis that all living amphibian groups, including caecilians, are more closely related to one another than any are to other extinct amphibian group.

Courtesy of Andrey Atuchin and Petrified Forest Museum Association.

Funcusvermis was discovered through two tenets of National Park Service paleontology: inventory and collections-based research. The site from which Funcusvermis is known is PFV 456, or as a Petrified Forest Field Institute class named it, Thunderstorm Ridge. PFV 456 was found in 2018 by Kligman and another PEFO paleontologist, Chuck Beightol (now at Vicksburg National Military Park), on a paleontological inventory of newly acquired lands that had previously been a cattle ranch to the east of the park. The bone layer itself is easily identifiable laterally, as it is chock full of coprolites and reptile teeth that weather out on the surface in abundance, a feature PEFO staff had noticed correlates with microvertebrates in the same layer in other parts of the park (Kligman et al., 2017, 2018). Over the field seasons of 2018, 2019, and 2021, park paleontologists, volunteer interns, and field institute participants listened to 1970s funk music and collected bones in field jackets and all of the surrounding rock matrix, totaling over 4000 pounds. This fossil-rich matrix was then divided into 5-lb. batches, soaked in water, and wet-screened through a fine mesh, after which paleontologists picked the fossils from each batch under high magnification. To date, approximately 85% of the material has been processed, resulting in thousands of individually catalogued microvertebrate specimens from nearly 60 different taxa, many of which are new to science. These include the burrowing drepanosaur Skybalonyx (Jenkins et al., 2020), the first mammal-like cynodont Kataigidodon from the Chinle Formation (Kligman et al., 2020), early dinosaurs and their relatives (Marsh and Parker, 2020), and now, Funcusvermis. Similar microvertebrate horizons have been found throughout the Chinle Formation at the park, which will allow PEFO paleontologists to continue to bring the funky fossils to light for scientific understanding and public enjoyment for decades to come.

References

-

Anderson, J.S., Reisz, R.R., Scott, D., Fröbisch, N.B., and Sumida, S.S. 2008. A stem batrachian from the Early Permian of Texas and the origin of frogs and salamanders. Nature 453: 515-518.

-

Evans, S.E., and Signogneau-Russell, D. 2001. A stem-group caecilian (Lissamphibia: Gymnophiona) from the Lower Cretaceous of North Africa. Palaeontology 44: 259-273.

-

Gee, B.M., Parker, W.G., and Marsh, A.D. 2019. Redescription of Anaschisma browni (Temnospondyli: Metoposauridae) from the Late Triassic of Wyoming and the phylogeny of the Metoposauridae. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 18: 233-258.

-

Jenkins, Jr., Farish, A. and Walsh, D.M. 1993. An Early Jurassic caecilian with limbs. Nature 365: 246-250.

-

Jenkins, X.A., Pritchard, A.C., Marsh, A.D., Kligman, B.T., Sidor, C.A., and Reed, K.E. 2020. Using manual ungual morphology to predict substrate use in Drepanosauromorpha and the description of a new species. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40: e1810058.

-

Kligman, B.T., Parker, W.G., and Marsh, A.D. 2017. First record of Saurichthys (Actinopterygii) from the Upper Triassic (Chinle Formation, Norian) of western North America. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 37: e136304.

-

Kligman, B.T., Marsh, A.D., and Parker, W.G. 2018. First records of diapsid Palacrodon from the Norian, Late Triassic Chinle Formation of Arizona, and their biogeographic implications. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 63: 117-127.

-

Kligman, B.T., Marsh, A.D., Sues, H.-D., and Sidor, C.A. 2020. A new non-mammalian eucynodont from the Chinle Formation (Triassic: Norian), and implications for the early Mesozoic equatorial cynodont record. Biology Letters 16: 20200631.

-

Kligman, B.T., Gee, B.M., Marsh, A.D., Nesbitt, S.J., Smith, M.E., Parker, W.G., and Stocker, M.R. 2023. Triassic stem caecilian supports dissorophoid origin of living amphibians. Nature 614: 102-107.

-

Marsh, A.D., and Parker, W.G. 2020. New dinosauromorph specimens from Petrified Forest National Park and a global biostratigraphic review of Triassic dinosauromorph body fossils. PaleoBios 37:1-56.

-

San Mauro, D. 2010. A multilocus timescale for the origin of extant amphibians. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 56: 554-561.

-

Stocker, M.R., Nesbitt, S.J., Kligman, B.T., Paluh, D.J., Marsh, A.D., Blackburn, D.C., and Parker, W.G. 2019. The earliest equatorial record of frogs from the Late Triassic of Arizona. Biology Letters 15: 20180922.

-

Wilkinson, M., Kupfer, A., Marques-Porto, R., Jeffkins, H., Antoniazzi, M.M., and Jared, C. 2008. One hundred million years of skin feeding? Extended parental care in a Neotropical caecilian (Amphibia: Gymnophiona). Biology Letters 4: 358-361.

-

Wilkinson, M., San Mauro, D., Sherratt, E., and Gower, D.J. 2011. A nine-family classification of caecilians (Amphibia: Gymnophiona). Zootaxa 2874: 41-64.

Related Links

-

Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home] [npshistory.com]

Last updated: March 22, 2023