Last updated: June 12, 2024

Article

Persevering Building 54 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center

This is a transcript of a presentation at the Preserving U.S. Military Heritage: World War II to the Cold War, June 4-6, 2019, held in Fredericksburg, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Bringing a Cold War Relic Back from the Brink

Presenters: Kim Daileader and Emily Eig

Abstract

In 2011, the Walter Reed Army Medical Center’s (WRAMC) Washington, DC, base moved to Maryland. As part of the BRAC process, the original base was designated an historic district encompassing 110 acres and almost 100 structures. Congress granted Children’s National Medical Center (Children’s National) a small parcel of the district. Since then, Children’s National has begun work to establish their first Research and Innovation Campus, the cornerstone of which will be a state-of-the-art pediatric, medical research laboratory within Building 54, a contributing resource. Balancing often competing code, environmental, preservation, and state-of-the-art lab requirements led to the identification of many innovative approaches to the adaptive reuse of a mid-century building, resulting in the charting of a new path for historic preservation.

Building 54 was constructed between 1951 – 1955 for the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology at WRAMC. It was placed in the far northwest section of DC, when escalating fear of nuclear war demanded the dispersion of critical government activities beyond the Federal core. The building was required by President Eisenhower to meet the specifications of the National Security Resources Board for bomb-resistant structures. It was the first and only in the US to be designed to survive a hydrogen bomb attack.

The building was designed to be completely operational in the wake of an attack and was intended to be the hub of activity for the president in such circumstances. The large central core of the structure is windowless, save for small protruding wings, which can be sealed by four-inch thick steel, blast doors. The concrete exterior walls are a minimum of twelve inches thick at the top and increase to two feet at the base. The south elevation, which faces the White House andUS Capitol, was built to withstand a blast of 14,520 tons. In the event of an attack, the HVAC and air-intake systems were designed to be completely cut off from outside air. The building even has a double-height TV studio to allow the president to film speeches and communicate with US troops around the globe.

This paper will discuss the challenges in bringing the historic Cold War-Era building into the twenty-first century. The issues are wide-ranging, from the lack of ADA-accessibility to the uniquely windowless construction. As Children’s National is a private non-profit organization all work had to be approved by the DC Historic Preservation Review Board, as well as meet DC Building Codes. Children’s National is also seeking Federal Historic Tax Credits, triggering National Park Service review for compliance with the Secretary of the Interior Standards for Historic Rehabilitation. Design and code challenges relating to a building with no windows, a critical character-defining feature, proved to be an immense negotiation between all stakeholders. Others included various abatement approaches, moving the main entrance, and meeting restrictive new environmental codes. Managing the competing interests and requirements has presented challenges that have only been touched on in preservation to date. This paper will share the challenges and solutions in dealing with historic mid-century buildings.

Kim Daileader, Lead Technical Preservation

Presentation

Emily Eig: Good afternoon. Can you hear me all right? I'm Emily Eig, and we are here today coming out of not a place where weapons are being protected, but a place where we'd be trying to be protected from weapons. As the nation's capital, Washington DC, has a unique position in all of this discussion, and particularly in the Cold War held a very problematic location. And resulted in many, many conversations about how best to handle that. But I'm going to talk about Walter Reed, which is the army medical center base that is in Washington DC. We're going to then move to the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, which Kim will take over for me and existing conditions of that building and the children's national rehabilitation of that building.

But let me start with a little bit of background on Walter Reed. As you can see from this map, Walter Reed is very far north in the location of the city... If I'm doing this properly... Oh, okay. How’s that...

You can see it's in the north. I'll go with that. It's that red do that says building 54 that is the Walter Reed. And you can see it's directly to the north of the White House and you see the Lincoln Memorial is to the West and the US Capitol to the East. The location of Walter Reed is one that you will see in a moment is quite a historic location for the military. And it's on this focus of 16th Street and Georgia Avenue, 16th Street being the center of our city in our minds, even though North Capitol Street is truly the center, but all things go of course around the White House.

So this location, I think I've missed a slide here. No, I didn't. Sorry. This location was the site of Fort Stevens, which is the site of the only battle from the civil war that took place in what are the contemporary boundaries of Washington, DC. It Is considered to be a hallowed ground and it was subsequently chosen as the site for the first national medical hospital that would then be named after Walter Reed.

Reed was a physician and he was the leading yellow fever researcher who determined that yellow fever was not contagious, but in fact was transmitted by mosquitoes. And that is not surprising that Walter Reed would have found that. Not because of who he was, but because the army was such a strong innovator in medical history. They were certainly the leaders starting from the revolutionary war and when they created in 1818 the permanently established Army Medical Division, which allowed the surgeon general to operate during times of war and peace. And other advancements happened at the front lines battlefield as well as last minute experiments on soldiers as they were in battles. And then during the civil war there were up to 204 makeshift hospitals during those battles. But then between 1870 and 1890 the discovery of microbes and the use of antiseptics post-surgery were very significant, obviously, not just for the army but for the medical profession overall.

And in 1905 the Walter Reed General Hospital was constructed. It was built on the 43 acres that included the Fort Stevens battle site. And it was this building, Building One that became the hospital. As you can see here, it soon grew and by 1921 this is an aerial view that you can see that the center is the Building One but it's been expanded. And there are many new buildings, barracks and the like going up all around it.

By 1922 they had purchased 113 acres and the American Medical College was created and shared the campus with it. It gets larger and larger as time goes on, more buildings are constructed and the Army Nursing School is built here as well as the Red Cross building. And then in 1955 in the upper left hand corner of the slide is a rectangular block of a building which is the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, which is Building 54.

At the time and we get into the 1990s, the BRAC process attacks Walter Reed, Walter Reed moves out of the District of Columbia to a nearby site in Maryland, but the base is then disposed of through GSA. Before they do that, of course they have to actually determine whether it is eligible for the National Register. And the army did do that. They created a period of significance from 1909 through 1956 and it was in fact listed in 2015. There are 49 structures on the site that are contributing and 49 that are non-contributing. It includes contributing landscapes as well.

The period of significance which will turn out to be important is from 1909 which is Building One to 1956 which is Building 54. This slide shows you what happened to Walter Reed as a campus. The green section was taken over by the District of Columbia, who then is sold it primarily to a private developer to develop as a neighborhood. A fully integrated neighborhood called the Parks at Walter Reed, but they are smaller owners throughout that. The blue part is what the State Department took over and the orange part was granted by Congress to the Children's National Research and Innovation Campus, which is part of Children's Hospital, which is the National Children's Hospital. The hospital, I think today, sometimes you might say, be careful what you wish for because this was a gift from the U.S. Congress to the hospital. But as Kim will explain, it has brought a lot of excitement with it as the hospital proceeds to expand its purposes from purely medical services into the true research and innovation that this campus affords them. Kim.

Kim Daileader: Hello. So I'm going to try and get through this without coughing. I'm the annoying one that keeps coughing in the back, so I apologize. There we go.

So the Army Institute of Pathology was founded as the Army Medical Museum in 1862 by Brigadier General William Hammond, an Army Surgeon General. The Museum was first located in Hammond's personal office and moved three times in the first two years of existence. Oh, that's really sensitive. Sorry. In 1866 the then private museum moved to Ford's theater after it was renovated after the assassination of President Lincoln. And the following year it was open to the public and drew 6,000 visitors a year by 1874, sometimes reaching over 2,600 daily. Specimens collected during the civil war contributed to the publication of the Medical and Surgical History of the War Rebellion and a comprehensive 6,000 page manual on a variety of ailments an army surgeon was likely to encounter was published between 1862 and 1888.

By 1885 however, the museum needed more space and Congress approved the appropriation of funds for new building. It's the building in the top right here. It was built in the 1880s by prolific DC architect Adolph Cluss and it is on the National Mall where today the Hirshhorn Museum sits. So this picture was actually taken in 1969 just as it was landmarked to then be demolished to make way for the Hirshhorn.

Between World War I and World War II, the museum began to struggle with lack of space in this museum, and by the end of World War I it already had over 100,000 specimens. In 1919 Congress approved the purchase of the land adjacent to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center. Though the Army Medical School moved into that new site in 1923, the Army Medical Library, 1933 the Great Depression sidelined the construction of a building for the Army Medical Museum. Funding plans for and specifications for the museum's new building was not approved by the House until 1940 but progress was again halted by the growing anticipation of war.

In 1946 and I apologize, that's a typo, not 1944 but 1946, the US Strategic Bond survey focused on projecting casualty rates on American cities based on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It concluded that an atomic attack on an American city like New York would produce similar casualty rates to those seen in Japan, but the government was optimistic about the United State's ability to plan and protect against atomic weapons with measures like greater use of reinforced concrete construction, tunnel shelters and population dispersal.

In 1947 the survey was followed by a report released by the War Department's Civil Defense Board, led by Major General Harold Bull. The report, known as the Bull Report, stated that civil defense is the responsibility of civilians, not the military and should be enacted at the local level. This report did not result in substantial action by the administration of Truman. In 1947 funds for the Army Medical Museum were finally cleared by Congress and the institution was renamed the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.

The first design of the building was a large glassy building and was released, but the Budget Bureau informed the Secretary of Defense that the projected cost of over $11 million was too expensive and that funds would be withheld unless the cost could be reduced by 40%. This requirement resulted in the significant change of the size of the building leading to the elimination of the planned Public Museum Wing, a large auditorium and space equivalent to two floors of laboratory space.

Congruent with that, in August of 1949 the Soviet Union successfully tested their first own atomic bomb. As a direct result, President Eisenhower, then the Supreme Allied Commander, directed that the new building for the institute of Pathology meet the specifications set forth by the National Security Resources Board for bomb resistant structures.

To allow the necessary changes in the design to be made the Bureau of Budget increased the allowance by 10% to a total of $7.5 million. New plans were drawn to incorporate the necessary bomb resistant features, including the elimination of windows and a reinforced concrete exterior. The building's outer walls varied in thickness from 16 inches at the base to 12 inches at the top, and that exterior walls were reinforced with extra heavy steel.

Unsurprisingly, reinforcement was greatest in the building's south wall, which faces downtown Washington and was built to withstand 27.2 pounds per square inch of pressure. The building can withstand an atomic blast of 14,520 tons. According to the army it's quote, "Design was a sensitive response to a difficult and very restrictive program as the structure was the first and only in the United States designed to survive a hydrogen bomb. At that point, the Soviets had successfully tested their own version.".

We can see here the distinctive details of the patch of the concrete formwork and in the top right as some of the details of the heavy reinforced steel that went into all the exterior walls. And here is a detail of the plan of the building. The interior walls surrounding the laboratory spaces were also reinforced. And I will kind of see if I can get this...

Oh good. So this is the main corridor and these are the laboratory walls. So we can see these are all reinforced with the heavy steel. And there's a central core that runs through the entire building from the sub-basement... I guess I should also mention there are three levels below ground of the building and five levels above ground. So this central core ran from the very bottom all the way to the top. The intention of the building was that this here would be all laboratory spaces where all scientific work would happen and then on the exterior was all kind of your expendable offices, meeting rooms and the like. These spaces right here, we're the only point where the building had windows.

Let's see, so this is the main... this is the facade of the building and again, the only expendable office and cafeteria spaces had fenestration. In the event of attack these spaces would be cut off from the central block by blast doors, thereby securing the building's main block. Additionally, if an attack occurred, the intake function of the air conditioning system servicing the main section of the laboratory would be automatically shut off to keep out radiation.

Each floor... Oh, I'm sorry. Let me see where I am... so each floor was to have also the lecture hall, rooms, teaching labs and offices for resident consultants. And the building also would accommodate the Armed Forces Medical Library and Advanced Teaching Museum and color television studio for producing medical training aids.

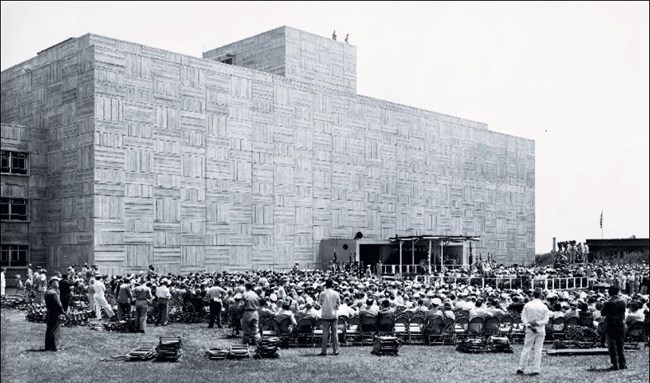

And this double height structure on the rear here is actually the television studio and it served as a dual function. It was meant to also be where the president would go should an attack happened on Washington, DC, before he went to Mount Weather he would be able to have closed contact with all of the armed forces around the world at that location. So this was the building when it was opened. The cornerstone was laid in 1953 and it was dedicated by Eisenhower in 1955. He can be seen giving his speech in this photo here.

Interestingly, a number of fragments were hidden inside of the concrete panels of the building, which I found to be intriguing. Fragments from the World War II atomic bomb explosions in Japan, including a piece of irradiated, radiation damaged lung tissue, fragments from a damage bone from an amputated limb of a civil war soldier, all made it inside the building.

In 1969 the Hirschhorn and sculpture garden was actually built on the National Mall, so therefore the museum had to go somewhere. So they completed the plans and expanded the building to the south. And this is called Building 54x. The museum artifacts were stored for two years here while the building was expanded. But it's important to note that the 1971 portion of the building is outside of the period of significance and it is non-contributing.

So this is the building as it stands today. It's important to note here that the State Department property line actually cuts right at this parking lot. So they own this whole parking lot. And this is the back of now what is the Children's National property. On the bottom left here we see one of the remaining wings of the original windows and this is the new entrance. It was expanded in the 1970s when they added the museum as well.

This here on the top left is the 1971 public museum entrance. This is the top of that building where they extended laboratories out. This is the rear of the original portion of Building 54 and this is the side/rear of the addition of 54x. The conditions are much like everyone else's buildings. When the Walter Reed picked up and left, they took everything with them. So it is a vacant building.

One of the more important things to note here is this is the main door and you can see actually the four inch blast doors here. There are eight located throughout the building so that if an attack happened, it could be completely sealed off from the wings. And this is one of the main corridors you can see there is absolutely no natural light, no windows, no nothing.

The building itself on the interior has been renovated multiple times. Some hallways here on the top left is in its original condition. This is another lab that the army had done as recently as 2001 even though they were already planning to leave. This here is the top level. It's the where the vivarium where they did testing on all the animals.

This is one of the more original laboratories that's still located in one of the basements, but this is kind of the general condition of what the majority of the building looks like. And this is the remainder of the museum here on the right.

So this is the campus as Children's National got it today. They have three buildings. Building 54 here is going to be their laboratory research center. This was the post theater for the Walter Reed base, and it's going to be their conference center. And this is one of the former ward buildings built in 1930 and it is going to be a clinic for children. And then they have a non-contributing parking garage. And so the plans are to do two tax credits. One will be done on this one and one will be done on Building 54. And I can just go into some of the detail of the challenges of bringing a 1955 cold war building and making it useful today.

One of the critical issues was the just the sheer lack of windows. Children's is trying to create a world class research center for children's cancer and no one wants to work in a windowless building anymore and there's no need for it to be a windowless building anymore. So there were a lot of discussions between us, the architects, Elkus Manfredi, who are out of Boston, the owner, the SHPO and the National Park Service. And it was first and foremost determined that this east facade needed to stay exactly that way. And so no windows will be added. This concrete will stay, this entrance will be returned. It will no longer be the main entrance, which will allow them to not have to remove those blast doors. And then this is the rear entrance and this is where the opportunities for new window openings will come.

So there are two options on the table currently. Right now the opinion is that if we do punched windows, you will still be able to read the concrete form work and understand that historically this was a solid wall. Another option could be just doing it on the projecting bay, but we're still in negotiations.

This is another one that has kind of bigger, more modern windows that don't reflect the historic window that are still located to the north. Again, this is something that we're still under discussion. Another serious issue that arose was abatement. The caulking that they used in the 1950s of course is riddled with polychlorinated biphenols and that needs to be fixed.

The EPA actually said that the correct way to do it would be to take all of the caulking out. You can see there's a big caulk line here. I believe there's another one right here. And saw cut all of the concrete around it to remove all of the contaminated material. Of course we told that to our SHPO and he said, absolutely not. Let's try something else.

So we tested a great number of sealants and we finally landed on one, it is this one right here down on the bottom. And what the process is that we are going to rinse the entire building with water at 150 psi and then cover all of the contaminated concrete on either side of a seal where the PCB was with this sealant. It is matte, it's not reflective and it will not change the color of the concrete.

So universal accessibility was again a huge critical issue. And this is the main entrance, it in no way meets code, you have to use stairs to get up to it. It's not wide enough. It has huge steel doors that are in your way. But it would be an incredible loss to lose that this was these historic blast doors. So we were actually of the opinion to move the entrance of the entire building to the rear here where it's the non-contributing old garage entrance. And that way... here's another pair of those steel doors. There's eight of them. This is one of the ones in the one of the tunnels.

But in order to do that, so this will... again their property line ends right here where these stairs are. So they're going to create a kind of tiny patio here that you can read the historic entrance and they won't have to mess with those doors and then they can create a new, glassy, nice public entrance. You know this building was never meant to be viewed by the public. No one that wasn't specifically, very specifically invited to this building was supposed to be in it. So now they will have a nice big entrance to signify this is that the center of their campus. This whole thing is going to be redone and look lovely and you can see they're going to have a nice big entrance here that will have elevator bays are going to have a public gathering space. And then if we go to the next level, you can see here are our tiny little cramped original lobby will remain just as it always was supposed to be.

So another issue was the corridor configuration. Again, the corridor walls are all doubly reinforced with heavy steel here on the interior where the labs are. So our first job was to determine what walls are original and what are not, beyond that. So we actually found out that the walls on the fourth floor were moved. Interestingly enough I don't know why they did that, but they did.

So the architects are going to going to be allowed to blow out this entire level and rearrange all of the rooms however they want. But the compromise was that where there are original corridor walls, they have to keep that configuration. Which they were not happy about. Because this is what the corridors look like. They're not very pretty. It's kind of a gross yellow tile, no openings, no windows, no nothing. So there was actually a lot of compromise and talking about what they were going to allow to do this.

This drawing was a little hard to read, but we were trying to compromise with the Park Service and SHPO and saying that maybe some of the walls could be glass walls. Some of the walls could be half walls, some of the walls could be pristine and not be touched and this is one where we were discussing it. It has its original form, but we were discussing maybe in this corner we could take out the entire corner so you when you're over here you could read the historic corridor, but here you have a little bit more flexibility.

However, because the walls are so thick and structural and because they are a character defining feature and there wasn't much else in the building to be preserved that didn't need to be ripped out for abatement anyway we did settle with SHPO that anytime the corridors are the figure eight and are still intact, they would have to remain intact with their beautiful yellow tile, which the architects have now embraced.

Another issue we have is that the doors themselves are not code for our current up to date laboratory. A lot of them have already been altered. You can see here they did this sometime in the 90s where they added what is a sidelight, a panel that opens so you can get equipment in and out. And our compromise for that was that wherever there is a door that needs to meet code it can meet code, but every single other door needs to be either preserved in place or we'll have a piece of glass to show the original opening and where it was.

So this here is just a little kind of diagram. It's hard to see but you can see the numbers of the doors. "Okay. This one will be expanded. This one will be glass. This one will be infill to show the amount of preservation in the building." And then this is just moving forward and these are things we don't have answers to yet is what we're going to do with special spaces? There are many unique spaces in this building. What do you do with... this is one of the blast doors that will not meet any sort of use in the future. This is the former cafeteria. They don't know what they're going to do there yet. This is an auditorium that doesn't have any historic fabric in it, but it's a volume of space that the Park Service will like to see retained.

One of the conversations is to take one of the older labs and preserve it with some of the leftover equipment that's there. And then again this is that TV studio, that two story height space that still kind of has the lights and camera equipment, all from the 1950s. This will be part of phase two but it will be intriguing to find out what the Park Service will and will not let them do with that space cause it is kind of drenched in history in a very cool area to be in. So hopefully we'll figure that out shortly. But that's it. Thank you.

Questions

Mary Striegel: Thank you. Who has the first question?

Speaker 1: Thank you for that. That was really interesting. As one who came from Washington, DC recently, I had no idea about the history of that structure. You mentioned that it's a lab facility and I get that the vertical walls are blast walls, but there's blast and then there's radiation fallout. How did you deal with the roof and the fact that there are labs with what I thought I saw where fume hoods which require roof penetrations.

Kim Daileader: Yes. All of that is going to be reconfigured through the center core. And so the roof is actually... well first of all, they expanded the, this building isn't really accurate to what it is. A level was added in 1971 but the whole roof, all of the mechanical systems, everything is being ripped out of the building and being in replaced with modern, smaller, more efficient equipment.

This is not a small project. This is a two phase project and the first phase is about $75 million worth of work going into this building. So they're redoing all of it.

Speaker 1: How did they deal with the roof penetrations initially? And was it a concrete roof?

Kim Daileader: Yes. So it's a concrete roof and it has that central core, so everything gets pulled up out of that core and then up out the building and then closed off if there had been an attack.

Mary Striegel: Other questions?

Speaker 2: So the addition that you mentioned that is non-contributing was designed by Edward Durell Stone.

Kim Daileader: Yes.

Speaker 2: So what kind of use is that going and will it ever be eligible on its own or?

Kim Daileader: So we were actually just talking about that today. It was an interesting decision. So they very strategically picked 1956 to be the end of the period of significance of the historic district because they wanted to get 54 in there. The museum itself is a National Historic Landmark. It is on the register, but that building was torn down. So it's kind of one of those things where it's not a contributing resource. We are getting the tax credits on it because it's considered one building by code, but it is being treated as a non-contributing portion of the building.

Emily Eig: Yeah. I think that the army did all of the work to determine what was important or not, what was significant or not and it's obviously a very large site with many buildings on it. The decision to leave out the Edward Durell Stone is one that I have marveled at how they actually... why they even thought to do that, but I think they were trying so hard to get the 54 in... the 70s wasn't even 50 years old when they were going through their exercise, so that must've been the reason that they did that.

Kim Daileader: But it will be a lab just like it was. It's going to be just a continuation of 54.

Emily Eig: They are removing the decorative interior that was the museum open spaces. But the rest of it, the building will... it will not go away. So...

Mary Striegel: Thank you, thank you so much.

Speaker Bios

Kim Daileader joined EHT Traceries in September 2013 after obtaining her MS in Historic Preservation in 2012. Initially after graduation she conducted post-graduate work at Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and then executed a year-long fellowship at the General Services Administration. Her background and undergraduate degree in structural engineering allow her to contribute to a wide array of preservation issues. Ms. Daileader works with architects, engineers, developers, property owners, and government agencies. She works on a wide range of preservation projects, including, Building Preservation Plans, Historic Structures Reports, Historic Tax Credits, National Register Nominations, Section 106, and Conditions Assessments.

Emily Eig established EHT Traceries in 1977. Her expertise focuses on preservation strategies, design review, and compliance with local, state, and Federal laws, as well as twentieth century architecture and historic interpretation. She is a recognized expert on the interpretation of the SOI’s Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties and Section 106. She has been an expert witness in numerous judicial and governmental venues over the last thirty-five years. Ms. Eig holds an MAT in Museum Education (Architecture/ Preservation) from The George Washington University and a BA in Fine Arts (History) from Brandeis University.

Read other articles from this symposium, Preserving U.S. Military Heritage World War II to the Cold War, or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.