Last updated: October 31, 2024

Article

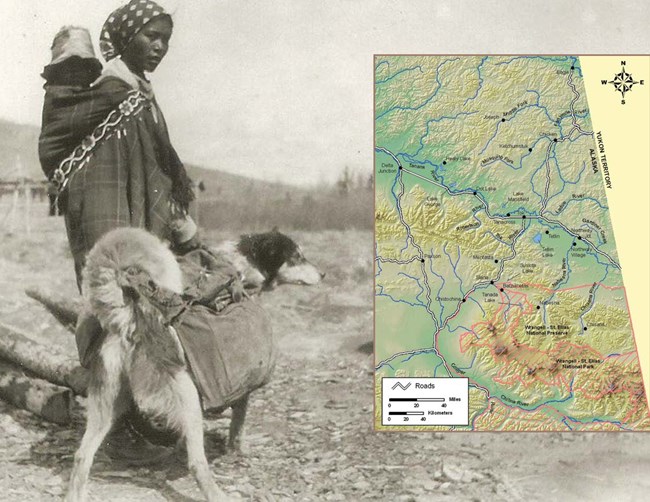

People of the Upper Tanana

William E. Simeone

By Barbara Cellarius, Terry Haynes, and William Simeone, 2007

Visitors to the northern part of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve may come away with memories of a spectacular mountain wilderness with glacial rivers, snow covered peaks, elusive wildlife and brightly colored wildflowers. Underlying these spectacular vistas, however, is a landscape of indigenous human habitation. To the Native peoples of the upper Tanana region, this area is not wilderness but rather their historic home, an area crisscrossed by trails and travel routes where they and their ancestors lived, traveled, hunted, fished, trapped, and gathered.

In 2002, the upper Tanana communities of Healy Lake, Dot Lake, Tanacross, Tetlin, and Northway were added to the list of rural communities that have special access rights to hunt, fish and gather within park boundaries, in recognition of their customary and traditional subsistence use of resources in the park. (This special access does not include the preserve.) Wrangell-St. Elias recently commissioned an ethnographic overview and assessment for the upper Tanana area (Haynes and Simeone 2007), focusing on these predominantly Alaska Native communities, in an effort to better understand their history and culture and their ties to the park. This report is based largely on existing ethnographic and historical literature along with archival materials, but the authors also drew on their personal fieldwork in the region. This article draws on that larger report and focuses specifically on these ties between Wrangell-St. Elias and Alaska Natives living in the upper Tanana region.

For purposes of this article and the larger report, the upper Tanana region extends from the Wrangell Mountains north to Joseph Creek and from the Canadian border west to the confluence of the Goodpaster and Tanana rivers. The region includes mountains, rolling hills and river valleys, numerous lakes and wetlands. With its subarctic climate, the region has long, cold winters and relatively warm summers with many hours of daylight and low pre-cipitation. Two main northern Athabascan languages – Upper Tanana and Tanacross – are spoken by Native residents of the region, although the number of Native language speakers is declining.

Settlement Patterns and Resource Use

The resource use and settlement patterns of Native people living in the upper Tanana region prior to sustained western contact were tailored to these sometimes difficult environmental conditions and the natural unpredictability of resource abundance. Aboriginal Upper Tanana Indians were semi-nomadic hunter gatherers who moved seasonally throughout the year within a defined territory to harvest fish, wildlife, and other resources. The key subsistence resources included whitefish, caribou, moose, waterfowl and muskrats.

The basic unit of social organization was a small extended family-based group of between 10 and 30 people, referred to as a local band. These kinship-based bands would split up or join with another group in response to shifting resource availability. Each band was associated with a particular geographic area or territory and had a number of camps and semi-permanent villages. These camps and villages were often sited in proximity to important subsistence resources. Seven regional bands have been identified in the upper Tanana area. The Upper Chisana/Upper Nabesna band territory fell largely within the northern portion of what is now Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve. In addition, the southern borders of several other bands overlapped with the territory included in the park. Until the early twentieth century, lead-ership in Upper Tanana society rested with “‘rich men,’ who were charismatic, enterprising individuals who combined an interest in others” with a degree of personal self interest (Haynes and Simeone 2007).

Sustained western contact in the upper Tanana region began in the early twentieth century. Residents initially acquired western goods through trade networks linked to the south starting in the mid 1800s, and then by traveling to trading posts outside the region. By the early twentieth century non-Native traders, trading posts and Episcopal missionaries had established a more lasting presence in the region. With the World War II came the construction of air fields and the Alaska Highway. Settlements began to develop at missions, trading posts, and along transportation links, and by the 1930s a much more sedentary lifestyle and residence in villages developed, in part as a response to federal government demands for mandatory school attendance. The adoption of firearms hastened a decline in cooperative hunting efforts such as the use and maintenance of extensive caribou fences. Other agents of change affecting Upper Tanana people in the twentieth century included formal western education, diseases, market hunting associated with mining activities, opportunities for wage employment, and government regulation of hunting and fishing.

Today’s Upper Tanana Native residents live in villages on or near the Alaska Highway or in the regional center of Tok. (Others have left the region and live in Fairbanks, Anchorage, or beyond.) Formal leadership in present day villages takes the form of elected village or tribal councils, although elders continue to be respected for their traditional knowledge and wisdom. The councils are recognized by the federal government as tribal governments. Although many adults are employed and patterns of resource use have changed, subsistence hunting and fishing continue to contribute substantial amounts to their diet and to sustain profound cultural values of sharing, the appropriate treatment of animals, and respect and appreciation of elders.

Upper Tanana Ties to Wrangell-St. Elias

Residents of the upper Tanana villages continue to harvest resources in the northern part of Wrangell-St. Elias – for example, hunting moose along the Nabesna Road or sheep in the Mentasta and Wrangell mountains. In many cases this is done under the provisions of federal subsistence hunting regulations and a permit obtained from the park. Many of the descendents of the Upper Chisana/Upper Nabesna band now live in Northway, Chistochina, and Mentasta and continue to hunt in the areas used by their ancestors.

In addition to the location of the band territories and continued use of those territories for subsistence activities, another factor in these interregional ties is the close relationships between the Native residents of the upper Tanana and the neighboring Ahtna region, in the form of intermarriage, trade, potlatches, and other kinds of inter-regional cooperation. Potlatches, which are gatherings involving the ritual distribution of gifts to memorialize life transitions and mediate conflicts, play a key role in bind-ing people from the two regions together. Additionally, people from Upper Tanana bands, with kinship ties to the Upper Ahtna, harvest resources in the Ahtna region, which also overlaps with the park. For example, salmon are not available in the upper Tanana River drainage, but through kinship ties to the Ahtna, residents of the upper Tanana villages harvest Copper River salmon. Ahtna people, in turn, sometimes hunted caribou near Kechumstuk. Further evidence of these ties can be seen in the extensive network of trails and travel routes that run between the two regions, with many of the trails crisscrossing what are now park lands.

Summary

This article is based on information presented in an ethnographic overview and assessment for the upper Tanana area that was prepared for the National Park Service (Haynes and Simeone 2007). The overview and assessment covers Athabascan culture in the upper Tanana region prior to sustained western contact at the beginning of the twentieth century and examines the traditional economy, sociopolitical organization, territory, language, ritual and religion, material culture, and trails. Additionally, it reviews changes that occurred during the twentieth century. An annotated bibliography for information on the history and culture in the upper Tanana region is also included. This larger report should be consulted for additional information about the topics discussed: Upper Tanana Ethnographic Study. Listen to oral histories of the Native people of the Upper Tanana River through Project Jukebox.

REFERENCES

Haynes, Terry L, and William E. Simeone. 2007.

Upper Tanana Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Wrangell St. Elias National Park and Preserve. Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Subsistence Technical Paper No. 325. Juneau, Alaska.