Last updated: March 17, 2021

Article

Patch-Burn Grazing

NPS

Introduction

North American prairies developed under the influence of fire -- both of natural and human origin -- and grazing. This history of fire and grazing provided disturbances that enabled grasses and herbaceous forbs to dominate the landscape. Native wildlife have adapted to these forces of nature, with some species preferring recently burned areas while others relying on relatively undisturbed habitat with dense vegetation and litter. Others have adapted to require both types of habitat to complete different activities within their lifecycles.Fire and grazing are key elements of natural resource management throughout much of the Kansas Flint Hills region and at Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve. A key management goal at the preserve is to create more natural patterns of burning and grazing, reflected in a shifting mosaic of burned and unburned, grazed and ungrazed areas. The result is an ecosystem that is healthier and more diverse in terms of plant composition and structure.

Heterogeneity in Grasslands

“Heterogeneity” is defined in the context of grasslands as variability in vegetation structure, composition, density, and biomass. It directly influences wildlife species diversity and ecosystem functions. Heterogeneity has been referred to as the root of biological diversity and should serve as the foundation for conservation and ecosystem management.

NPS

Interaction of Fire and Grazing

One grassland management practice that is gaining favor among biologists, ecologists, and range managers is patch-burn grazing (PBG). This fire-induced regime approximates the natural interaction between fire and native grazers. Typically, one-third of each PBG pasture is burned every year on a three-year rotational basis.Fire affects grazing patterns, and grazing patterns affect the extent and intensity of fire. Grazing animals preferentially feed in recently burned areas for foraging because the post-fire new plant growth is more palatable.

When only a portion of a large pasture is burned, grazers prefer foraging in burned patches and avoid grazing in the unburned patches. This results in accumulation of vegetation in unburned areas, creating fuels for fires in subsequent years. The interaction of these disturbances produces a shifting mosaic of plant communities within grazed grasslands. Experts believe that similar fire-grazing interactions helped shape the pre-settlement ecology of the Great Plains and other grasslands that had large grazers and a long history of fire.

This burn regime also provides larger fuel loads, resulting in more intense burns that may help to control trees and shrubs from encroaching on the prairie. This technique may also prove effective in invasive plant control.

David Besenger, MO Dept. of Conservation

Effects on Wildlife

The diverse grassland structural stages that result from PBG provide habitat for a broad range of wildlife species, including greater prairie chicken and Henslow’s sparrow.Plants and animals respond differently to fire and grazing. For example, some bird species prefer to nest in areas recently burned with little or no cover, while others prefer to nest in unburned areas that feature considerable plant height and old vegetation build-up (litter).

Many species of animals use all areas under PBG treatment, but in different segments in their life cycles. The greater prairie chicken may choose to boom (male mating display), nest, rear young, forage, and seek cover in all of the various vegetation structures provided by patch-burn grazing.

NPS

Implementation

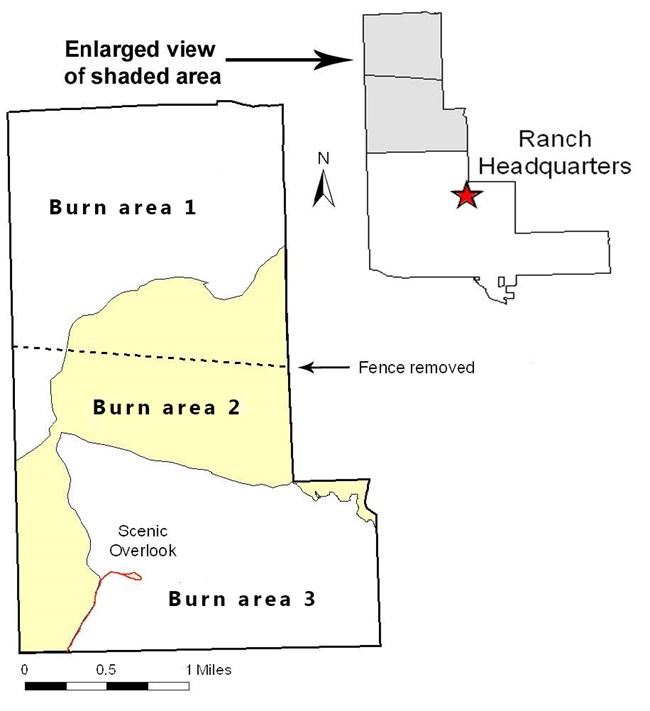

At Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve, working in close cooperation with its cattle grazing lessee, The Nature Conservancy is partnering with the National Park Service to implement patch-burn grazing in suitable areas of the park. In order to more effectively implement this practice, managers removed 1.7 miles of cross fence between two existing pastures, creating a single large grazing unit. Creating fire breaks and working with the natural topography enables specific areas to be burned, leaving taller “old growth” prairie plants in place, thereby creating a more randomized, and more naturally-occurring, landscape.

NPS

Long-term Monitoring

The staff of the National Park Service and The Nature Conservancy consider sound management of natural resources at the preserve a top priority. Long-term monitoring will help managers determine if management practices are having the desired results.The National Park Service’s Heartland Network Inventory and Monitoring Program and others have gathered baseline data on plant and animal communities on the preserve. The network will continue to monitor indicators of ecosystem health to detect ecological trends over time. Trend analysis will inform managers about how patch-burn grazing has changed structural and biological diversity. These analyses will warn of any unanticipated impacts, allowing managers to fine-tune their practices to adjust to an ever-changing ecosystem.