Part of a series of articles titled Park Paleontology News - Vol. 12, No. 2, Fall 2020.

Article

Paleontology of Channel Islands National Park

Justin Tweet, NPS Partner—Paleontologist

American Geosciences Institute

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

Channel Islands National Park has one of the best fossil records in the National Park Service. In fact, it is one of 18 National Park Service units that have paleontology mentioned in the legislation establishing them. All five of the park’s islands have yielded significant finds, and fossil species have been named from all five. Rocks and deposits ranging in age from the Late Cretaceous to the Holocene have preserved a great variety of fossils, from tiny single-celled plankton to pygmy mammoths. Study of these fossils goes back to the 19th century, with the first published mention in 1865.

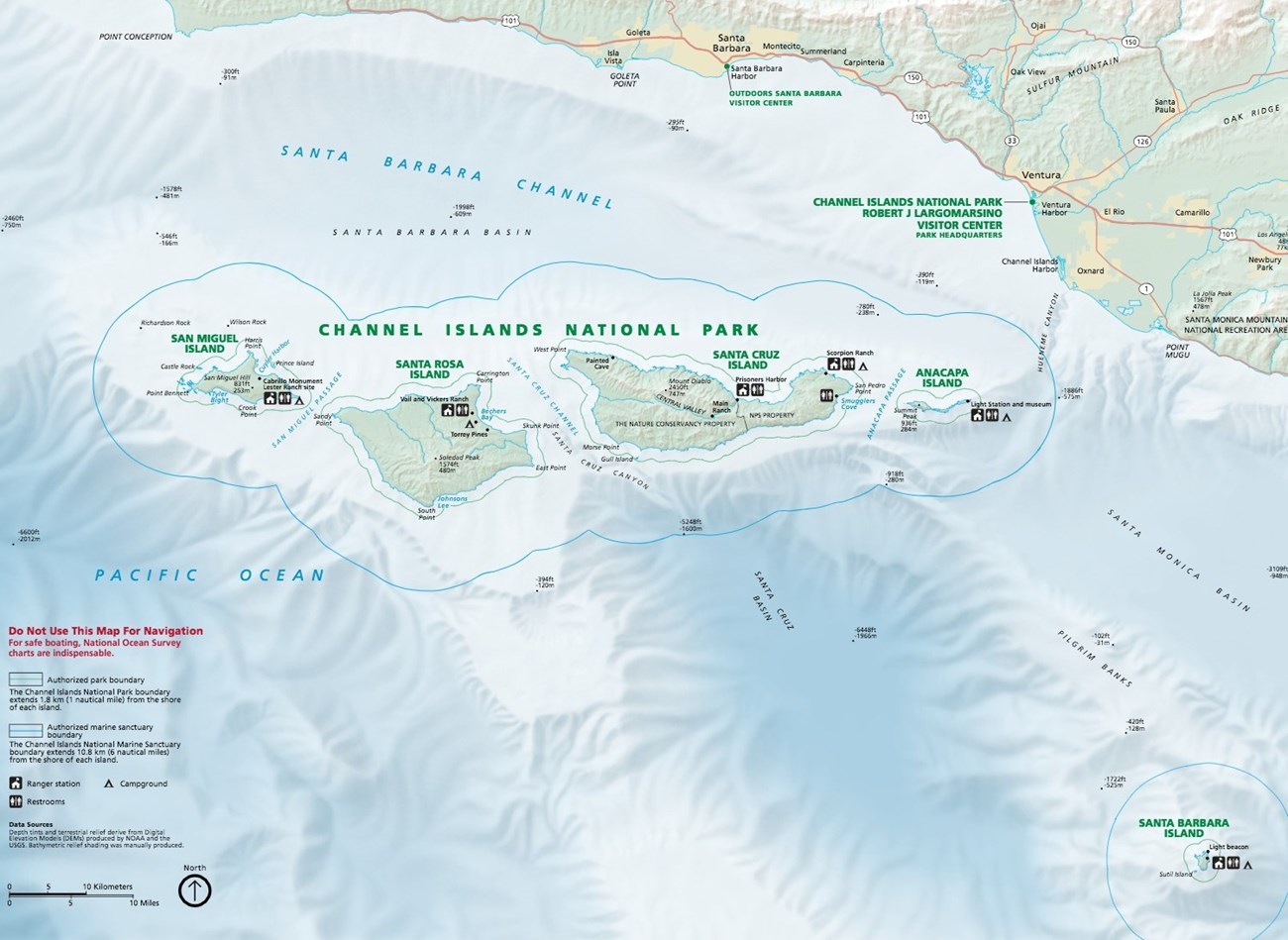

Channel Islands NP consists of five islands located off the coast of southern California. Four of them make an east-west line approximately 100 km (60 miles) long. From west to east, they are San Miguel Island, Santa Rosa Island, Santa Cruz Island, and Anacapa Island. The fifth island of the park is Santa Barbara Island, about 65 km (40 miles) southeast of Anacapa Island. Channel Islands NP was proclaimed as a national monument in 1938, and originally included only Anacapa Island and Santa Barbara Island. The other three islands were added in 1980, when the monument became a National Park. In 2019–2020, the paleontology program of the NPS’s Geologic Resources Division made the first paleontological inventory of the park. A public version of this report can be found at https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2278664.

NPS image.

The four northern islands of the park have an unusual geological history. Until about 20 million years ago, they were part of a north-south ocean shelf attached to California near San Diego. Plate tectonics along western North America caused the block of land including the northern Channel Islands and what are now the Transverse Ranges of southern California to be wrenched out of place and transported north. The block caught on the continent and rotated clockwise about 90 degrees, as it is today. The northern Channel Islands can be considered a continuation of the Santa Monica Mountains. The tectonic activity also led to large volumes of lava erupting; lava beds are found on all four northern islands, but the islands themselves are not volcanic. Santa Barbara Island has a different history, but is also mostly made of volcanic rock.

Because the Channel Islands were beneath sea level for most of the geologic history recorded in the rocks we see there, most of the fossils are marine. Paleontologists in the 1960s tested many of the rock units for microfossils, which they could use to provide relative dates for the rocks and to get an idea of the general environmental conditions (water depth, cool or warm water, etc.). The scientists documented hundreds of species of tiny marine organisms based on mineralized shell-like structures. No other park has had such detailed investigation of microfossils. Other marine fossils are common throughout. They include specimens of diverse snails and bivalves, sea urchins, corals, barnacles, crabs, and many others.

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

Among the more unusual marine fossils are bones of desmostylians and sirenians (sea cows). Desmostylians were strange marine mammals that looked something like a sea cow with four stout hippo-like limbs and no tail fin. Desmostylian bones were found on Santa Cruz Island in the 1960s but have not been described. Bones of two Early Miocene sirenians were found on Santa Rosa Island in the 2010s and are under study at this time.

During the Quaternary, which began 2.58 million years ago, the islands of Channel Islands NP became exposed above water due to uplift and changes in sea level. At some times, less of the islands was exposed than at present, while at times of low sea level, such as during ice ages, the four northern islands were connected as one large island. This large island is called Santarosae or Santa Rosae. Although in the past some scientists thought that there was also a connection to the mainland, study of the seafloor topography shows that this did not happen. We can see evidence for this in the fossil record of the park: there are no plants or animals that would have had to spread by land. All of the organisms that populated the islands in the Quaternary could have safely arrived by water or wind. Mammoths, which were strong swimmers, could swim to Santarosae, but other large mammals could not.

Channel Islands NP has an especially good record of fossil birds, the best in the National Park Service. Bird fossils are found in caves, where they were concentrated by roosting birds of prey, and in the sediment, where there are nesting burrows of small seabirds. Several species of seabirds used the islands for nesting colonies, including the extinct flightless sea duck Chendytes. Other animals were not as diverse. There were only a few species of mammals, mostly rodents, including extinct “giant” deer mice; the islands were also home to the extinct vampire bat Desmodus stocki. A hand bone from a short-faced bear has been found on San Miguel Island, but it was most likely transported there by a large bird of prey that scavenged it from the mainland. Reptiles and amphibians are also only known from a few species. Land snails were very abundant, but again, represented by only a few species. These animals lived in a much more forested environment than today; plant fossils from Santa Cruz Island show that there were stands of Douglas-fir, with plant life more like that of the area around Fort Bragg, 685 km (425 miles) to the north-northwest. At the time, the setting was cooler and moister. Calichifed “fossil forests” representing the roots of lemonade sumac shrubs and trees are a well-known feature of San Miguel Island.

NPS photo.

By far the most famous fossils of Channel Islands NP are pygmy mammoth bones. Pygmy mammoths descended from full-sized mainland Columbian mammoths that swam what was then a few miles to Santarosae, probably smelling the fresh vegetation on the island. As happened on other islands, the body size of the mammoths became smaller over time to adapt to the smaller landmass. Pygmy mammoths averaged 750 kg (1,750 lb) and 1.7 m (5.6 ft) tall at the shoulder when fully grown. Mammoth bones have been reported from the islands since at least the 1870s, but it wasn’t until 1994 that a nearly complete specimen was found. This find greatly increased interest in the paleontology of the islands, and researchers have since spent many years surveying for new finds. Weathering and erosion can proceed very quickly on the islands, so it is important to document new finds and respond quickly if they warrant collecting. A large skull of a not-quite pygmy, not-quite mainland mammoth was excavated in 2016 and is being studied to see how pygmy mammoth evolution took place.

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

You might not think of people as potential fossils, but the most ancient human bones in the National Park Service were found on Santa Rosa Island. Also known as “Arlington Man,” this person lived between approximately 13,494 and 13,291 years ago. The most recent pygmy mammoth fossils date to about this time frame as well, so it is possible that humans and mammoths briefly coexisted here. Channel Islands NP has a long archeological record that is intertwined with the park’s Quaternary fossils. In fact, it has been suggested that the island foxes and skunks did not arrive there by themselves, but were brought there by people early in their time on the islands.

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

The fossils of Channel Islands NP are an important part of the islands and their natural history, as well as our national paleontological heritage. If you should see a fossil while visiting the park, feel free to take photos, but remember to not remove or disturb it; share your find with a Park Ranger instead.

Related Links

- Channel Islands National Park, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- NPS—Fossils and Paleontology

- NPS—Geology

Last updated: October 8, 2020