Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

Over Here, Over There: America and World War I

Text of an exhibition - commemorating the centennial of American involvement in the First World War - on display, in the visitors’ center at St. Paul’s Church N.H.S., from February 2017 through January 2019.

Introduction:

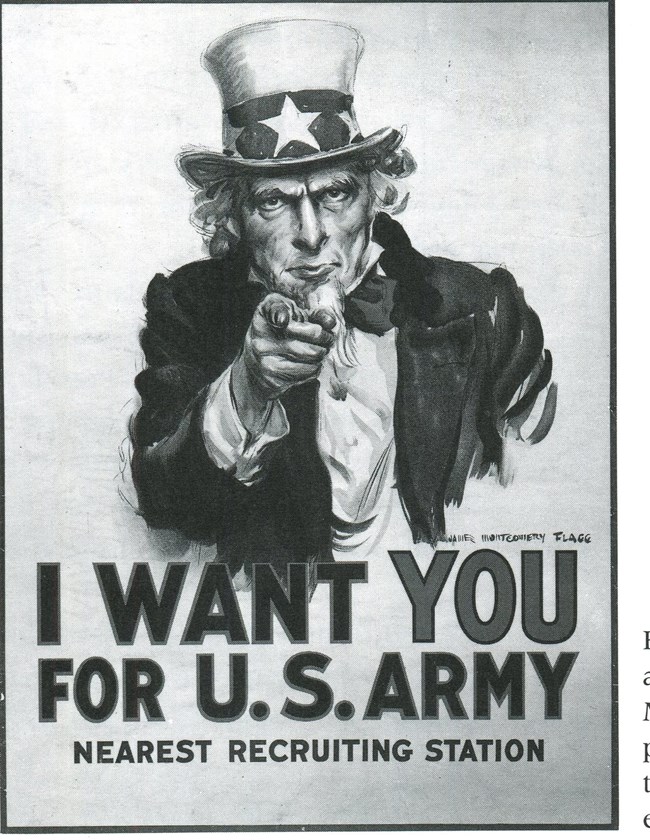

Trenches, soldiers called Doughboys, George M. Cohan’s patriotic song Over There and posters with a white bearded Uncle Sam telling potential recruits “I Want You” characterize the popular memory of World War I. The death in 2012 of the last surviving United States soldier from the Great War ended the living connection with the conflict of 1914-1918. But what was America’s role in the War to end all Wars? How long were we involved, and what impact did the conflict have on the country? This centennial of American entry into the war presents an occasion to explore a fascinating chapter in our nation’s history.

America’s active participation was relatively brief. We declared war on April 6, 1917, and the Armistice ended the conflict 19 months later, on November 11, 1918. The period of heavy combat was even shorter, with soldiers fighting on the battlefields of France in large numbers only from May through November 1918. But for such a short duration of intense conflict, the war was costly; about 110,000 Americans died in the line of duty, including five soldiers buried at St. Paul’s.

President Woodrow Wilson characterized American involvement as a crusade to “make the world safe for democracy.” For several years, the Democrat from New Jersey tried to prevent American involvement by attempting to serve as a peace maker and arbiter between the warring European powers. From 1914 to 1917, an intense national public debate considered which side to favor, and whether the United States should be drawn into the conflict across the ocean.

Innovative approaches to financing the enormous cost of the war and guaranteeing public support for the effort were developed. Restrictive laws and citizen vigilantism controlled antiwar activities -- not all Americans supported involvement in what seemed to many a bloody, senseless stalemate. A war against Germany -- the birthplace or ancestral home of millions of Americans -- created difficult and sometimes dangerous living conditions for citizens of German descent. Despite initial problems with coordination, America’s enormous industrial capacity was eventually directed toward delivering the materials of war. On the home front, public support for the war was expressed through a variety of war bond campaigns and patriotic programs. Portions of the population, especially women and African Americans, who had not achieved full rights of citizenship, demanded that a war for democracy include greater inclusion at home.

Marking the centennial of American entry, we invite you to explore this interval in our history through prints, documents, photographs, art work, sound, artifacts and text. This exhibit was made possible by:

National Park Service/Department of the Interior

The New York Council for the Humanities

Society of the National Shrine of the Bill of Rights

BMC Mt. Vernon

Panel 1: Preparedness From 1914 to 1917, the Great War raged in Europe. The Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire battled the Entente alliance of Great Britain, France and Russia. The United States waited impatiently on the sidelines, hoping the conflict would end without a need for American participation. But the overwhelming majority of Americans in 1914 traced their ancestry to one of the European nations, creating an immediate interest in the war across the ocean. Individuals and organizations, notably the American Red Cross, supplied medical relief and humanitarian assistance to both sides, establishing precedents for overseas benevolent efforts by Americans. At the beginning of the conflict, President Woodrow Wilson urged neutrality, but issues of commerce, publicity and heritage produced strong support for the Entente cause. American industrialists supplied munitions and other war materials to those European powers, and the nation’s agricultural products increasingly fed British and French soldiers, generating an economic surge.

A national debate waged over whether the Americans should continue offering financial and material aid to the Entente Powers; some argued against any economic involvement. A far more strident argument emerged over the question of Preparedness, the term used by those who wanted to build the nation’s armed forces in case the country was pulled in to the war. Among the leaders of the Preparedness movement were former President Theodore Roosevelt and General Leonard Wood. They called for a military buildup and increased weapons production. President Wilson initially opposed this strategy, philosophically opposed to war and fearing that involvement in a foreign expedition would undercut his domestic reformed agenda. By the fall of 1915 the president, fearing political charges of negligence of duty, moved to a position of moderate preparedness.

Reports in American newspapers of the carnage and frightening casualty rates suffered by combatants in the European trenches generated strong opposition to Preparedness. Anti-preparedness (a contemporary term) forces included peace advocates like settlement house leader Jane Addams, pacifists, progressives, Socialists (a strong political movement of the day) and some of the more radical labor union chapters. Parades staged by preparedness and anti-preparedness groups filled the streets of the nation’s larger cities. Perhaps the largest drew 135,000 people, including President Wilson, to a Preparedness march along Fifth Avenue in New York City in May 1916.

Important wartime events influenced the American preference for the Entente cause. German attacks on civilians in Belgium at the onset of the war, skillfully exaggerated by Entente propagandists and widely reported in American newspapers, created a perhaps unfair public perception of the Germans as barbaric, the Huns. Outgunned on the high seas by the powerful British navy, the Germans resorted to sporadic submarine warfare and attacked Entente and American passenger and merchant ships carrying goods from neutral nations into the war zone around Britain. These attacks led to several human tragedies, notably the Lusitania in 1915, when 128 Americans were among the 1,198 people killed when a German U boat sank the English ocean liner. In response, President Wilson demanded that Germany cease attacks on merchants and passenger ships, and for a time, after two more controversial sinkings, Germany agreed it order to prevent the United States from entering the war.

The German decision in early 1917 to resume un-restricted submarine warfare to deprive their enemies of munitions and food moved President Wilson to break diplomatic relations with Germany. American sentiment against Germany was further hardened by the discovery of the Zimmerman telegram, a secret initiative by the Germans to encourage Mexico to declare war on the U.S. and fight to reclaim territory surrendered during the Mexican War of the 1840s. All of these developments, along with Wilson’s desire to play a role in spreading democracy and crafting the peace settlement, spurred the president to ask Congress to declare war on Germany. Congress complied on April 6, 1917.

Panel 2: Financing the War

Wars are expensive propositions, and World War I was no exception for the United States. Financing the war was especially challenging since the Federal Government was much smaller than today, with an annual budget of less than $1 billion. (The war ultimately cost about $33 billion.) In addition, the urgency of World War I required coordinating human and material resources on an unprecedented scale.

Following the declaration of war, a Congressional debate explored questions about financial responsibility for the war costs. Wisconsin Senator Robert La Follette, who had voted against the declaration of war, led an unsuccessful campaign for steep increases in personal income and business taxes to require wealthier Americans to contribute proportionally to the fiscal burden of the conflict. The most innovative response to the challenge was the Liberty Bond campaigns, conceived and managed by the Secretary of the Treasury William McAdoo, who was the son in law of President Wilson. Through four separate war bond drives, the Federal Government gained about $22 billion, dispensing low interest treasury notes payable in 30 years, and covering about two-thirds of the total war cost.

Campaigns to sell these bonds involved the entire country, emerging as the clearest venue for ordinary citizens to express patriotism and support of the fighting men. They also created some of the war’s enduring images. These included movie stars Charlie Chaplin, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. encouraging people to support the troops through bond sales at massive rallies on the steps of the Sub-Treasury Building (today’s Federal Hall) in lower Manhattan. Colorful, evocative Liberty Bond posters expressed American war themes, from bright and positive expressions of democracy, to gruesome suggestions of German barbarities. Even the historic St. Paul’s church bell, dating to 1758, was employed as a symbol of America’s historic treasures at some of the rallies.

The bond drives tried to connect the public to the war effort, and about 30-percent of the notes were purchased by people earning less than $2,000 (about $31,000 in today’s equivalent). The remainder of the bonds were sold through banks and financial institutions. These results were actually disappointing to Treasury officials, who had expected a higher level of participation by the general citizenry. Most of the aggressive public relations strategies were employed in the third and fourth drives seeking to stimulate direct investment by consumers of modest means. That’s when the Boys Scouts and Girl Scouts got involved. A particularly dramatic strategy was linking the purchase of bonds to spectacular, daring air shows to capitalize on the novelty of aviation. Elite pilots of the Army Air Corps performed entertaining and dangerous stunts at scheduled air shows in open field and meadows. Upon completion, these airmen announced sales pitches for Liberty Bonds, producing some of the most impressive success rates of the enterprise.

Panel 3: Promoting the war effort

A variety of campaigns were developed to help establish a consensus of public support behind the war effort after April 1917. The outreach activities designed to solidify support for the war utilized emerging concepts of public relations and advertising, two of the growing service industries of early 20th century America.

Responsibility for the persuasive public awareness campaigns was assigned to the Committee of Public Information (C.P.I.), directed by George Creel, a Western crusading journalist and one-time police commissioner. Headquartered in Washington, Creel’s agency coordinated an effective propaganda campaign utilizing community volunteers, highlighted by the concept of the Four Minute Men. The initiative was named for the time between reel changes at the silent movie houses during an era when about ten million people attended the motion picture features each day.

Four Minute men delivered rapid fire speeches, announcing common themes of American democracy and explaining the war’s goals “to make the world safe for democracy,” according to President Wilson. These monologues drew a clear distinction between American democracy and German autocracy. Some of the deliveries utilized emotional appeals about alleged German atrocities.

Supervised through a central administration in Washington, the Four Minute men program was actually organized through a decentralized system of state level and local chapters. The volunteers were often men accustomed to public speaking -- lawyers, journalists, and teachers. The program moved beyond the movie houses, and Four Minute speeches were delivered in churches, lodge meetings, union halls, service clubs and schools. Despite the label, women delivered these speeches particularly to address women’s groups. The CPI also recruited African American clergymen, teachers and community leaders to address black audiences, and created a special division for Work Among the Foreign Born to cultivate patriotism among immigrants. By the end of the war, approximately 75,000 men and women had delivered the brief talks to an estimated 314 million listeners, in a nation with a population of about 100 million people.

Panel 4: Supporting the war effort:

World War I provided opportunities for people who had not obtained full rights of citizenship to demonstrate their value and role in the nation’s social and political landscape. Some women and African Americans who supported the war effort anticipated advances in their conditions and rights.

The woman suffrage movement (the effort to achieve the vote) was among the leading social and political issue of the day, and a major beneficiary of the war. Most activists seized upon the opportunity to demonstrate the patriotic, indispensable role of women at a time of national emergency. Chapters of the Women’s Land Army, often associated with colleges, worked as farm laborers, filling the gap of male agricultural workers who had joined the army. Women joined auxiliary units of the armed services, and worked as telephone operators and clerks. Women gained employment in war related industries; they helped to support the Liberty Bond campaigns. Perhaps most dramatically, they sowed bandages, assembled care packages and provided medical services on an unprecedented scale under the auspices of the Red Cross, which experienced record growth during the war. These activities accelerated a pattern of recognizing the basic citizenship of women and led to growing and ultimately successful support for women’s suffrage, codified in the 19th amendment to the Constitution, passed in 1920.

African American also hoped to achieve a more inclusive level of citizenship through support of the war. The 1910s were a period of increased, organized black protest over segregation and disenfranchisement. Many African American leaders, notably W.E.B. Du Bois and the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), encouraged support for the war as a means of demonstrating a credible role in the nation, hopefully leading to post war improvements in their lives. Often facing extreme prejudicial obstacles, black citizens volunteered to support the cause on the home front.

The war years witnessed a historic migration of African Americans from the rural South to the urban centers of the North and Midwest, known as the Great Migration. Mt. Vernon’s black population, for instance, increased during these years. Drawn by employment opportunities in war related industries, these migrant enlarged black communities in cities like Cleveland, Chicago and Detroit. Virulent prejudice and racial discrimination resulted in some of the nation’s worst race riots occurring northern cities experiencing this influx, especially in East St. Louis and Chicago. Black men were over-drafted in numbers relative to their population, and served in segregated units mostly as non-combatants. Two combat divisions fought with honor in France, but few white Americans were ready to recognize their patriotism. Their contributions to the war failed to yield post war social and economic gains, frustrating African Americans’ aspirations.

Panel 5: Protecting the war effort:

The Congressional vote for war in April 1917 was overwhelming, but not unanimous. Fifty-four members of Congress voted against the war declaration compared to one negative vote in December 1941 for the World War II declaration. Even after the declaration of war some Americans refused to drop their objections to fighting. Expressing those opinions, however, became much more dangerous and in some cases illegal in a series of developments that reflected the tensions of upholding civil liberties or the concept of loyal dissent during a national crisis.

President Wilson sought unanimity of vision and expression, and at his urging Congress passed two restrictive laws designed to silence critics of the war. The Espionage Act of 1917and the Sedition Act of 1918 made it illegal -- punishable by fines and imprisonment -- to actively encourage resistance to the war effort. Hundreds of people were arrested for delivering antiwar speeches and many, including Socialist party leader Eugene Debs, served prison time. Enforcement of those two laws was often under the jurisdiction of local district attorneys, and prosecutions could vary widely. Socialist Kate Richard O’Hare delivered the same speech in several states, but was convicted and sentenced to a prison term of five years for her remarks in North Dakota. In context of heightened tensions, even casual remarks casting doubt on the draft or the war effort could lead to legal difficulties. A Mt. Vernon man, for instance, whose son faced the draft, was overheard hoping America might lose the war and hauled before the magistrates. (The Supreme Court upheld the Espionage Act as constitutional, arguing that words intended to “create a clear and present danger” were not protected by the First Amendment.)

Resistance to conscription was minimal, but did exist. The War Department allowed members of a limited number of pacifist denominations (Quakers, Mennonites) to serve as conscientious objectors eligible for non-combat roles. Other draft resisters were castigated as “slackers” and they were often badgered or insulted into service. The American Protective League, a quasi-official organization, organized a series of highly publicized “slacker raids” in the fall of 1918, rounding up and arresting scores of men who looked like they should be in the army, with approval of local law enforcement.

World War I revealed the internal conflict created during war against a foreign power in our multi-ethnic, immigrant based nation. German immigrants or people of German ancestry represented one of the largest ethnic groups in America. Suddenly in 1917 Germany was the enemy. How would the declaration of war affect millions of these Americans who overwhelmingly considered themselves loyal citizens of the republic?

President Wilson’s public warnings about German or German-American security threats inspired a broad assault against all things German in American society. Sauerkraut was called Liberty cabbage; hamburgers were renamed Liberty sandwiches, German measles was re-diagnosed as Liberty measles. Families of German descent adopted variations on their last names that sounded less German. Berlin, Michigan was renamed Marne, Michigan (honoring those who fought in the Battle of Marne). The town of Berlin, Shelby County Ohio re-constituted its original name of Fort Laramie, Ohio. Brooklyn’s Hamburg Avenue was changed to Wilson Avenue.

German immigrants had to register as “enemy aliens,” even as their American born children were drafted into the army. They faced restrictions, for instance, on employment in war related industries. Many were arrested and jailed. Communities, school boards and universities banned teaching the German language and culture, suddenly interpreted as cultivating autocracy, militarism and barbarism. Other localities restricted and discouraged studying German, including Mt. Vernon in the fall semester of 1918. Reflecting a common theme across the nation’s press, the local Mt. Vernon Argus supported the school board, charging: “No American who is conscious of the inhuman characteristics of Germany wants to learn the language of the barbarians.”

Panel 6: Mobilizing for war:

The American army had fought its last significant war in 1898. Since then, advances in military technology had introduced a range of weapons -- machine guns, tanks, airplanes, heavy artillery, poison gas -- that were utilized by armies along the Western Front. American military leaders had little experience with these lethal tools of war. How could the nation mobilize, organize, equip, transport and train a force of millions to fight with these advanced weapons on another continent? These were the challenges confronting President Wilson and Secretary of War Newton E. Baker in April 1917. By November 1918, nineteen months later, they had succeeded beyond reasonable expectations.

The American army of early 1917 was a small peacetime force of about 125,000, augmented by approximately 160,000 National Guard troops. Millions would be needed for the European conflict, and the process of creating these large forces highlighted a perennial controversy over the relative advantages of a volunteer force as opposed to a conscripted army. The majority of the army was raised through the implementation of the Selective Service Act. Passed by Congress in May 1917, the act required all men between ages 21 and 30 – later extended to ages 18 through 45 -- to register for a draft. The draft ultimately raised about 2.8 million, or more than half of the 4.8 million armed forces for the war. A student of history, Wilson avoided the calamities of the Civil War draft which, among other inequities, permitted men of wealth to purchase substitutes if they were selected. For the war of 1917-18, troops were selected through a series of de-centralized draft boards administered by local, accountable officials and community leaders, decreasing the impression that men were being enrolled by anonymous bureaucrats. All eligible men had to register, although exemptions were granted to men with dependents or those engaged in war work.

Because of America’s traditional respect for private enterprise and the tremendous power of large corporations, the Federal Government was reluctant to nationalize manufacturing and transportation industries. The result was an initial inability to effectively marshal and utilize America’s vast industrial capabilities and wealth in support of the war effort. A crash course in national mobilization occurred throughout the spring of 1917, with much trial and error and innovation. By the spring of 1918, through the coordinating efforts of the War Industries Board under financier Bernard Baruch -- including partial nationalization of railroad transportation -- the nation had improved the practice of funneling materials and men to Europe.

American soldiers, nicknamed “doughboys,” had to prepare for the rigors and dangers of war. The responsibility to train these large armies fell to overworked, quickly trained officers. Hastily assembled and overcrowded military camps created hazardous conditions, in which disease flourished. The troops were especially vulnerable to the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-19, among the most deadly contagions in history. Four soldiers buried at St .Paul’s -- Ensign John Walter Hodge, Private William Maier, Private Stuart Robinson and Private John Richard Griffith -- succumbed to the disease. Because of a shortage or often lack of weapons, recruits sometimes marched carrying wooden rifles or spent little time on the shooting range. Stateside training consisted of drilling in the rigors of military discipline, physical fitness and marksmanship. Overseas, the doughboys learned the obstacles of trench warfare and how to mount and sustain attacks. Despite all of these obstacles, America ultimately created a sizable, credible military force that dispatched two million soldiers to France under the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.).

These were not the Civil War era soldiers who were accustomed to rifles, and many urban recruits had never deployed a firearm. The typical soldier stood 5’ 7” and weighed 142 pounds. With compulsory education laws just coming into widespread existence, about 30-percent of the men were classified as illiterate. One fifth of the force was foreign born, and Army officials charged with censoring soldiers’ letters in Europe had to contend with 49 languages. With just 4,000 slots reserved for black volunteers, over 96% of the 367,710 African Americans who served during the war were conscripted. The 200,000 black soldiers who went to France experienced a welcome from civilians and soldiers unlike anything they had ever encountered at home.

Panel 7: Fighting the War:

America’s active participation along the Western Front was relatively short. The large scale presence commenced in the spring of 1918, and increased steadily until the war ended on Armistice Day, November 11, a period of only about six months. The commanding officer of the A.E.F. was General John J. Pershing, a West Point graduate from Missouri who had risen through the ranks as a cavalry commander. His greatest accomplishment was creating an independent American army that occupied its own sector, providing valuable manpower to a combined Allied offensive that began in September and ended with victory. The sheer number of fresh troops introduced into the theater -- at one point in 1918 about 33,000 Americans were reaching the combat areas of France on a daily basis -- and the expectation of more to come played a decisive role in Germany’s decision to seek an armistice. The highly visible contribution to the Allied victory also secured President Wilson a prominent role in peace negotiations.

On the battlefield, the A.E.F. made several strategic and decisive attacks that contributed to the victory on the Western front. In late May, the American Second Division played a major role in halting German advance units at the Battle of Chateau-Thierry, preventing the Germans from reaching Paris. Perhaps more importantly, in mid-July large numbers of American soldiers played a key role in stalling the Aisne-Marne offensive, the final German assault; after that, Germany was on the defensive. The Meuse-Argonne operation of late September through the armistice was the largest land battle the American army has ever fought. Attacks by nearly a million American troops forced hundreds of thousands of German soldiers to defend vital installations, permitting the British and French troops to score sweeping victories to the north and east.

American soldiers performed notable acts of courage and bravery during the Meuse Argonne offensive. The war’s most famous hero was Private First Class Alvin York of the 82nd Division, who had failed to receive conscientious objector status. He was credited with single-handedly silencing an entire German machine gun battalion, killing at least 20 enemy soldiers and capturing 132 men, leading his column out of an enemy entrapment. The Lost Battalion of the 77th Division -- men from the New York City area -- captured the public’s imagination when, surrounded and running out of ammunition, they held out for five days, rejected demands for surrender, despite heavy losses, and were finally relieved by advancing units.

The discriminatory practices of the day didn’t prevent the all-black, 369th Infantry Regiment, the Harlem Hellfighters, from compiling an impressive record on the battlefield. While most African American troops were assigned duty as labor and support personnel, the 369th was one of four black infantry regiments that General Pershing transferred to the French Army. Respected by the French for their fighting abilities, the 369th served more days at the front lines than any other American unit. Fifteen soldiers of the Harlem Hellfighters earned the French military honor Croix de Guerre, including Corporal Morris Link of Mt. Vernon, who was killed in the German advance at the Marne River on July 15, 1918, and later interred at St. Paul’s.

For all the individual feats of bravery and competence, the Great War was a brutally impersonal, deadly series of engagements. The mechanized efficiency of the machine gun and the arbitrary nature of aerial artillery attacks caused death and destruction in ways that threatened confidence and zeal. While American casualties pale in comparison with the European belligerents, the A.E.F. paid a heavy price for its months of active combat. An average of 300 Americans were killed in action daily from late May 1918 through the Armistice. Total American deaths were about 116,000, with about 52,000 of those falling in combat, and most of the rest succumbing to disease, particularly influenza, or the Spanish flu, which infected the ranks of all the armies in the fall of 1918. Towns and cities throughout the nation diligently recorded the names of the fallen on monuments and plaques, including Mt. Vernon, where trees were planted in honor of each of the 85 men from the city who died in the war.