Last updated: September 1, 2021

Article

Orlando Nace Oral History Interview

NPS

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH ORLANDO NACE

NOVEMBER 20, 1985INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI

INTERVIEWED BY PAM SMOOT

ORAL HISTORY #1985-6

This transcript corresponds to audiotapes DAV-AR #3080-3082

HARRY S TRUMAN NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

EDITORIAL NOTICE

This is a transcript of a tape-recorded interview conducted for Harry S TrumanNational Historic Site. After a draft of this transcript was made, the park provided a copy

to the interviewee and requested that he or she return the transcript with any corrections

or modifications that he or she wished to be included in the final transcript. The

interviewer, or in some cases another qualified staff member, also reviewed the draft and

compared it to the tape recordings. The corrections and other changes suggested by the

interviewee and interviewer have been incorporated into this final transcript. The

transcript follows as closely as possible the recorded interview, including the usual starts,

stops, and other rough spots in typical conversation. The reader should remember that

this is essentially a transcript of the spoken, rather than the written, word. Stylistic

matters, such as punctuation and capitalization, follow the Chicago Manual of Style, 14th

edition. The transcript includes bracketed notices at the end of one tape and the

beginning of the next so that, if desired, the reader can find a section of tape more easily

by using this transcript.

Jim Williams reviewed the draft of this transcript. His corrections were

incorporated into this final transcript by Perky Beisel in summer 2000. A grant from

Eastern National Park and Monument Association funded the transcription and final

editing of this interview.

RESTRICTION

Researchers may read, quote from, cite, and photocopy this transcript withoutpermission for purposes of research only. Publication is prohibited, however, without

permission from the Superintendent, Harry S Truman National Historic Site.

ABSTRACT

Orlando Nace (May 25, 1887—January 18, 1987), was a piano tuner and violin makerfrom Independence, Missouri. He and his son tuned the Truman’s piano at 219 N.

Delaware Street over a period of approximately fifty years. Nace explains the tuning

process and maintenance of the piano in the Truman’s music room and what occurred

when he visited the Truman home to tune the piano. He also discusses his piano tuning

business and many customers.

Persons mentioned: Harry S Truman, Bess W. Truman, Madeline Boston, Bernard Zick,

Rufus Burrus, Margaret Truman Daniel, Theodore Steinway, Milford Nace, Cammy

Johnson, Madge Gates Wallace, George Porterfield Wallace, St. Mary’s Academy (Sister

Mary Frances, Sister Marie, Sister Mary Lee), May Wallace, Vietta Garr, Tony Caldwell,

and Nell Kelly.

ORAL HISTORY INTERVIEW WITH ORLANDO NACE

HSTR INTERVIEW #1985-6STEVE HARRISON: This interview is with Orlando Nace. It’s being conducted at

Rest Haven Nursing Home on Truman Road in Independence,

Missouri, on November 20, 1985. Conducting the interview is

Pam Smoot, historian with the National Park Service in Omaha.

ORLANDO NACE: I see this table, which reminds me where our president is now over

there. See those men sitting around. Think of the responsibility of

those few men for the world. That’s why they think I’m an old

man. Why should I keep up with all those things? I like to keep up

with them.

HARRISON: I’m just going to mention that I’m going to be operating the recording

equipment, so you can just ignore me. Except I’ll give Pam a signal when

the tape’s about to run out and ask you to just pause for a few minutes

while I change and put on the new tape. Otherwise, I’ll try to be just as

quiet as a mouse.

NACE: Don’t make no record now.

HARRISON: I’ve got it on. It’s all right.

NACE: I better keep my mouth shut for a while. [chuckling]

PAM SMOOT: Don’t do that. Can I call you Orlando?

NACE: That’s right.

SMOOT: Would you tell us what your full name is, please?

2

NACE: It’s Orlando Nace. The full name, Orlando Pearl Nace. P in the middle of

it.

SMOOT: When were you born?

NACE: In Knob Noster, Missouri.

SMOOT: What year? When’s your birthday?

NACE: May 25, 1887.

SMOOT: How long have you lived in Independence?

NACE: Since I was eighteen. Now, you have to figure that out. [chuckling]

SMOOT: Did you know the Truman family?

NACE: I’ve known them for a good many years, over fifty years.

SMOOT: When did you first meet them?

NACE: I couldn’t tell you the exact date. It was before he ever started to get into

politics to be the judge of Jackson County. It was before that.

SMOOT: So what did you think of Harry?

NACE: Well, I think he was just like a brother to everybody. That’s what I think.

He’s a man that never did feel above you. A very fine man.

SMOOT: What did you think of Mrs. Truman?

NACE: I think the same thing of her. And her brother, too, because I worked

with him one time. [chuckling]

SMOOT: What were you guys doing?

NACE: Working in the planing mill, and I was in cabinet work.

3

SMOOT: What printing mill?

NACE: The west end . . . oh, what do they call it? They called it a mill, but it

was for making everything, see?

SMOOT: Do you remember where it was?

NACE: Down on the end of Elm Street, down in there, the west end.

SMOOT: So what is your occupation, or what was your occupation?

NACE: Well, I’ve had three. I came to Independence when I was eighteen years

old, and I worked one winter for a company that had feed and coal and

stuff just driving a team, at $9 a week. [chuckling] Good wages then. And

I boarded for four and a half a week, so I got about half. Well, I worked

there for one winter, and I worked the next summer in an ice plant

company with a man that delivered ice all over Independence. That’s

where I learned the names of lots of people at that time.

And I had friends in the Kansas City Bolt and Nut Works—they

call it another name now—in Sheffield, and they got me in there. And the

boys that was over the rolling mills, Sturges boys, was friends of these men

that worked in the machine shop. I got in there at fifteen cents an hour

[chuckling], worked a while, and then I got onto the rolling mill, on the

mill part itself where they make all the rods and everything. Well, I

worked on that. I had a guarantee of six dollars and something a day. That

was big wages to me. I worked on that for, oh, pretty near two years. I got

4

hurt awful bad and it paralyzed me for three months. Well, I changed from

that, come back up to Independence, lived here, and I took up the cabinet

work at that time. Went back to the planing mill. That was the name of it.

I worked there for quite a while, and while I was there I studied piano

tuning, and that’s how I got into it.

I wanted music. I took violin for five years, learned to play good,

but I didn’t want to take playing for a profession. So that’s when I got into

piano tuning is right there. I took school from the Niles Bright School in

Michigan. I finished there, why, I started tuning for friends first, just one

here and there and there, and I bought old pianos and made them over to

get experience. During that time, I think I tuned different ones right in the

neighborhood of where Truman was. Madeline Boston graduated from the

school, she was a teacher, several other teachers in there, and Bernard Zick,

he was the head of one of our banks here, and I tuned for them. That’s how

I guess I got in. And Rufus Burrus and Mr. Truman was great friends. He

was a lawyer. I tuned for them. They was very fine people and fine

pianos. Music got behind me and teachers behind me, and the chamber of

commerce, all of them backed me in my music work. I worked with

orchestras and I had a big band four years the chamber of commerce

sponsored. And I just gradually got . . . [chuckling] well, I had too many

more than I could deal with.

5

My boy got out of high school, and he wanted to go into public

accounting. He grew up with piano tuning, so I got him in it, too.

[chuckling] And then we worked together for over sixty years. We rebuilt

pianos, done everything to them that could be done.

And the Trumans took me on early. Margaret was only about ten

years old about that time. She was planning to . . . Well, she had a good

voice. She was aiming to sing. And I just kept on tuning, and I never quit.

Well, when he became judge, you know, from that and he went on into

politics, got to be president, and they moved the piano from the home to the

White House during that time. Well, Theodore Steinway sent another

studio piano to Truman and wrote his name in it. Well, every time

Margaret would come home, Mrs. Truman would ask me to come and see

if the piano was in good tune. And every time that she’d come home, I’d

tune that piano.

Well, [chuckling] I was going to tell you something that happened,

but I didn’t. Well, anyhow, I was always welcome. I had a habit of

parking across the street from the house, and I pushed a button at the gate,

and they’d open the gate from inside, you see, and I’d come on in. Well,

Mrs. Truman said, “Mr. Nace, you don’t need to do that. Come on around

here and come in here and come in this way with me here.” Well, here’s

what happened. [chuckling] I went around there and stopped with my car,

6

and got out and took my tools out of the back end of the car. And the man

who was a guard there come out of his little house looking at me and

looked like he was scared. [chuckling] He thought I had a bomb, I guess,

or something. Mrs. Truman saw him, and she come out on the back porch.

“That’s all right, that’s my tuner.” [chuckling] We visited a little bit and

went on in. That was one incident that was kind of . . . oh, it made me kind

of . . . I thought it was funny. Anyhow, those things happen.

Well, this other thing that happened after that while Harry was

still in the White House and I come in there . . . Every time Margaret

would come home, I was there to tune the piano. And she wanted . . .

one of her brothers, they lived two houses just east of them. And there’s

another thing I can remember, too, since I’d been in there tuning. They

wanted the piano tuned, one of them did, and Mrs. Truman told me there

was nobody home and the key was at a certain part in the back porch, to

get a key to get in. Well, I went in the wrong house. The key was

where she said it was, and I went in the wrong house, and no piano in

there. I was afraid that man would see me and think I was a robber and

not know what I got into. [chuckling] Well, I came back, put the key

up, and I went to the other house, and the key was in the same place in

the back porch. I went in, the piano was there, I went ahead and tuned

it. But those things happened while I was . . . [chuckling] just in my life,

7

you know.

All those years, they went by, but I was always treated like a man

that was respectable. And both of them, Mrs. Truman was . . . She wasn’t

a woman of high society and all that stuff, you know. She was just a good

woman. But I loved the family, and I still love them. And the last time I

tuned, I talked to Harry was he was home after he was president. He came

down and sat over there on the north side of the room and talked to me

quite a little while before I left. That’s the last time I ever saw Harry.

And then the three years that . . . It was three years went then

before I come back again. Mrs. Truman had been sick so much, you know,

quite a bit, and so she called and had me come back again—that was after I

broke my hip—and I went down and tuned the piano. And I thought there

were signs of moths in it. And I wasn’t able to take the action out, lifting

the thing whether or not it was broke up here. And I told the lady to take

the strip off along the front and spray something in there to kill moths, you

know. I guess she did it, because it went again a while. And last week, or

the week before, my son went down to tune it for her. She called again.

Another thing was . . . now, the way the family is now. She was

upstairs—

SMOOT: Who was upstairs?

NACE: Mrs. Truman was when I went down to tune, and they brought her down so

8

she could talk to me little bit and things while I was there. You see, that

was nice. And I never saw her anymore after that. But they was just

always nice to me.

And I respected him. When he ran for judge, I voted for him then.

He had these ideas for trestles over those tracks on Sheffield. You know,

that’s a big . . . it always held up traffic and everything, and he wanted to

see things built over them. He put big things at each side for a foundation

to start with, and then there wasn’t enough money to keep it going. I

thought about his ideas, ahead that much, you see, because it had to be

done. We know they are now, you see?

And I followed him all the way through the presidency, while he

was the president, too. And during that war, it was a terrible strain. I don’t

know, when he was on the campaign, I kept track of his campaign even

while he was in some town on the back end of a train talking. [chuckling]

And I looked at the picture on the television and watched him. But I was

interested in the man. That’s the reason I paid attention to the man, to see

what his decisions would be. When it come to that one to put that bomb

down, I thought, my, that’s a terrible responsibility on the man. He

realized it too, what it would do, but it had to be done, that’s all, in the

conditions. And it proved out that way. You can see it did afterwards. It’s

bad that men have to do it, but Harry made a decision and he stuck to it.

9

That’s the way he was in his campaign. [chuckling] I watched the things

they put in the paper about it and all that stuff.

Well, as far as Harry Truman and them, I still respect that family. I

worked with her brother down there in that planing mill. He was there. He

was one of the boys. And I won’t forget the family.

SMOOT: You just mentioned that you spent some time in the Truman home with Mr.

Truman after he had come back from the White House.

NACE: Yeah.

SMOOT: And he sat down and talked to you for a while. What did you guys talk

about?

NACE: Oh, we talked about some of the things that was going on in the world, of

course, naturally. I don’t know, just mostly people around that we knew

and things like that, you know, and how things was going in Independence.

He was always interested in Kansas City and Independence just as well as

the United States. But just things that come up before us, just good friendly

talk, and some of the experiences he had. He had some tough times. There

was opposition to him, just like there is today, but when Harry made up his

mind to do something, he went ahead and did it. He meant to do it, too.

[chuckling]

SMOOT: Mr. Nace, do you remember when you first tuned their piano?

NACE: When I first tuned it? No, I couldn’t tell you the date. It’s all in books I

10

have. But the books, I don’t know where they are now. We kept books on

all those jobs, the date that the order come in and when it was done and

how much I charged and the dates and everything. It was always on the

books. That’s the second wife. She kept those things good.

SMOOT: While you were tuning the piano, did you ever have coffee or tea with

either Bess or Harry Truman after you tuned the piano?

NACE: Ever have what?

SMOOT: Did you ever have a cup of coffee or a cup of tea?

NACE: No, we didn’t. We never did that. The English people did some, but I had

a lot of others offer me beer and wines and stuff. [chuckling] Truman

never did. No, we never did that.

SMOOT: When you tuned the piano, approximately how long did it take?

NACE: Well, the average tuning would take you about . . . take at least two hours. I

always doubled my tuning as I went. You see, each octave tuned perfect. I

test this octave before I’d tune this one again. And I’d make sure the high

end, if it happened to be a little low, I’d tune it again. Then the tuning

would stay good. You change the piano pitch a half a tone, you have to put

three times more pull on it, and that’s why I say, it’ll give some to it. Them

iron plates hold the strain. The Steinway is a very fine piano to tune. We

have about four or five pianos that’s the best makes, and Steinway I, the

style A is one of the best scales of Steinways. I’ve tuned the big Bs and

11

others too at the music club in Kansas City and places.

SMOOT: Did any of the Trumans ever watch you while you tuned the piano?

NACE: Well, I don’t know that they did. Miss [Vietta] Garr was in and out once in

a while, just doing things around, you know, but always was quiet when I

was tuning. Oh, sometimes people talk to me when I’m tuning, but it

bothers you because you have to hear the sound waves while you’re tuning.

No, they never bothered me that way, but they was always friendly.

SMOOT: Usually when you were in the Truman home tuning the piano, what was

Mr. Truman or Mrs. Truman doing while you were tuning the piano?

Were they sitting somewhere else in the home?

NACE: Oh, they would be somewhere around in the home. They’d be upstairs or

somewhere around. Harry didn’t stay at home very much. You see, he

was in politics, and he was in the office in the city most of the time

somewhere.

SMOOT: Did the Trumans ever have any visitors around sometimes when you were

tuning the piano?

NACE: Have what around?

SMOOT: Any visitors? Any company?

NACE: Oh, yeah, they’d come in, but they never bothered me at all.

SMOOT: Did you know any of the people?

NACE: Oh, like I say, like the Burruses and . . . well, the man who was in the

12

banking business, the families like that, they would come in and talk. But

they’d go in another place to talk, and I don’t know . . . to visit.

SMOOT: Do you have any idea about how much money the piano that the Trumans

had, do you know how much it may have cost or how much it was worth?

NACE: You mean at her place?

SMOOT: The piano in the Truman home.

NACE: Well, when I saw it in there first we was always getting two and a half a

tuning, and we gradually raised to three, then three and a half, and four, and

then up to four and a half and five, kept coming up, you know, until later

on when they raised the price still more and we went to fifteen dollars. My

son and I held at fifteen for a long time, and the other tuners went up to

twenty. Now they’ve gone clear beyond reason. [chuckling] They go too

far now, I think. Thirty-five dollars is more than they should have.

[chuckling]

SMOOT: So how much do you think the piano was worth? How much did the piano

itself cost?

NACE: Well, that model they have would have cost when they bought it around

$1,500. And I sold some . . . I worked for Jenkins five years as a special

salesman and did extra tuning for them once in a while when they got

behind, and I sold some of them for $1,900 and $1,800, in the A style. See,

that was more on the M style. That’s middle between the smaller one and

13

the A. There’s another medium in there that’s a good size. That would

cost at least $1,500, theirs would have. Now you couldn’t get it for $3,000.

[chuckling]

SMOOT: Could you tell by looking at a piano whether it’s new or used?

NACE: Yeah. There’s several ways you can tell that.

SMOOT: How can you tell?

NACE: And how it’s used, the kind of use it’s had, by the wear in the action. You

can tell that more than anywhere else, the wear in the action. And tuners,

in turning the pins, get the pins loose quicker than other tuners, the way

they handle the tuning hammers. There’s a secret there, what we call

equalizing the string tension. The way they use the hammer on that pin,

you can loosen it in the block. Now my son and I both, I don’t know how

many Steinways and Hammonds and Chicories and others we’ve put new

pin blocks in them. When the pinning gets loose, other tuners will drive

that pin in a little bit and they don’t put anything underneath. Well, that’s

made of layers. And it will push a layer off on the bottom, or they can

crack the pin block. We have to take that plate out of there with the block

on it and fit a new block to the plate and put it back in and string it again.

Milford was just offered a job last week to do that old Chicory grand now.

He don’t want to do it anymore. We’ve done a lot of the pianos like that.

Some pianos was old pianos. There’s a Beckstein piano made in Germany

14

that’s a very fine piano, and the girl that . . . a very fine pianist, her block

split. It was thicker than the ones you can buy from the houses where we

buy those blocks already put together, but we have to saw them and fit

them to the plates after we get them, you see. Well, I had to build that up

and make it thicker. There’s where cabinetwork come in handy with me

with piano tuning. I could take the piano case off of a piano that was in a

fire and remodel it, put new veneer on them and everything. And the

Steinway piano in the high school in Independence, I had to put two layers

of veneer clear around that piano—a fire burned it all—and put a new top

on it. Things like that. That’s why our tuning people thought more of us

than tuners: we could do anything to a piano. And that’s where I got all

these years of experience. But it’s too bad I can’t keep at it now.

[chuckling] I still could do it. No strength.

SMOOT: Could you tell by looking at the Truman piano whether it was new or used?

NACE: Well, it shows good use. Even though it’s used, the varnish don’t show

much. The right kind of finish. A lot of your pianos finished with a

different kind of varnish years ago, they check awful bad. Well, that tells

something.

But every piano I tune has got a number on the pin block, and I can

tell the age of the piano by . . . I have a book that’s got those pianos when

the Steinways even started way back, and who made them and what year,

15

the date and the number. And that number . . . Jenkins has a book on it, I

had a book when I was in business, too. I could tell . . . look at your piano

and I’d look at that number, and I’d look it up and see when it was made,

what year, by that number. Everybody don’t know that, but we do. If I’m

a piano trader, I look in the piano, and I buy four or five at the time at the

auctions. I go in ahead of stock, ahead of the sale and pick out the pianos I

want to buy, you see.

Well, the experience you have with these pianos, you know what

kind of care they got. These jazz players that play them hard, they wear a

hammer through. Miss Cammy Johnson is one of my favorite customers, a

teacher, she wore hers through just teaching till they get to the wood. I put

a new set of everything in that piano new about two years before she died.

Jenkins bought it for $1,000 after she died. And Mrs. Theisman over

looking around for . . . maybe she’d make a change, and they wanted

$5,000 for the piano, Jenkins did. [chuckling] They refinished the case.

That piano was perfect. I put brand-new hammers, back checks, felts here,

and new tops on the keys and everything before she died. Miss Cammy

was a good friend of mine. She wouldn’t let a pupil buy a used piano until

I looked at it.

SMOOT: Do you know what year the Trumans’ piano was made?

NACE: No, I couldn’t remember that. I wouldn’t know unless I took that number

16

and looked it up. That’s the only way you could. I know they had it when

I first began tuning, and that’s all. It never was wore out [chuckling].

One time at our tuners meeting in Lawrence, all of us was out there,

and the newscaster come in to make a note of our meeting, you know, and

the boys all bragged, “Why,” they said, “we even have the tuner in our

organization that tunes for the president of the United States.” They

thought it was big, you know. [chuckling] I’ll never forget that.

SMOOT: What was the name of your organization?

NACE: The Kansas City Guild, they called it, of Piano Tuners. It was the National

Association of Piano Tuners. That’s what they called it then. And then in

Kansas City we had it first, the Kansas City Tuners Association, and then

they changed it to the guild or something like that.

SMOOT: Did you know Madge Wallace?

NACE: Who?

SMOOT: Madge Wallace?

NACE: No, I never met the Wallace girls. I just met George is the only one I ever

met.

SMOOT: George? You didn’t meet anyone else?

NACE: No, not the rest of the family, I didn’t. Only Mrs. Truman.

SMOOT: Can you tell me anything about George that you remember?

NACE: Oh, George was just like the rest of us young fellows. That’s all I know.

17

[chuckling] He was a good friendly boy, though. He worked in the mill at

the same time I did. Yeah, I knew George then. But we never associated

like the Burruses. The Burruses, I could call them anytime. I could tune

again for them. She didn’t like anybody else. Sisters of Saint Mary’s

Academy, they sure hated to give me up, too. I tuned sixty years for them.

SMOOT: When the Trumans shipped Margaret’s piano to Washington, D.C., did you

help with the preparation to send it to Washington?

NACE: No, I don’t know whether they shipped it or drayed it. I don’t know which

way they took it.

SMOOT: Did you ever go to Washington, D.C., to tune the piano?

NACE: No, I never was there.

SMOOT: You said something earlier about a lady who came down and pulled the

strip off of the piano because you couldn’t do it.

NACE: That was Miss Cammy Johnson.

SMOOT: Miss Cammy Johnson? Who was that? Who was she?

NACE: She was a music teacher, and she was the organist at the Christian church

for years till she got her ankle, her foot hurt some way, and she had to give

it up. No, I always took the books off of the piano and all the stuff piled

and laid it on the floor. When I got through, I put it back for her. She

wasn’t able to do it. She finally went down to a place at Lee’s Summit, and

that’s where she died. All that property goes into the city for the antique . . .

18

It goes in with that bunch. The Truman home goes in it, too.

SMOOT: Were you ever invited to the Truman home for any special occasions?

NACE: No, never was.

SMOOT: Did you ever work on any of Harry’s campaigns?

NACE: No, only I talked to my friends for it. [chuckling] That’s the way I

worked. I just told my friends what I thought. You know I was for him,

naturally. I voted for him every time he run for it, too.

SMOOT: So, Orlando, when did you tune the piano? Did you just tune the piano

when Mrs. Truman would call you?

NACE: Yeah.

SMOOT: Or did you tune it on a regular basis?

NACE: No, it was when they called me. But that was often enough, because every

time Margaret would come home . . . Well, it didn’t take me much time to

tune them if I kept them in tune. I can straight tune a piano in one hour,

right straight through. But your unisons will never stay as good if I do it

that way because it’s the way I leave the pin turned the last time. And it

takes more time to do it that way.

SMOOT: How many times do you think you tuned that piano?

NACE: [chuckling] The dates that’s in it. That’s the only way I could tell. If I

went back and got my books that we kept I’d know. But I don’t do that.

SMOOT: Do you know how many times Milford has tuned the piano?

19

NACE: Well, I know he tuned it the last time it was tuned, this last time. That’s all

I ever know that he ever tuned it, because I was the one that did it all the

time. That’s the way most of the time for Burruses, too. He has tuned

there, too.

SMOOT: Do you remember what year you worked at Jenkins Music Store?

NACE: Well, let’s see, that must have been in the ‘20s, because I come here in

1916 and I was already married and everything. I was twenty-one and past,

and I had already learned piano tuning after that, see. It was 1912 or 1914,

along in there, is when I was tuning for the public, because I did other work

in those other years. No, Jenkins, they liked having me stay there, but I

never . . . I did tune a whole year for the Star Piano Company, their

wholesale stock in Kansas City, and I had the vice president stand by me

and talk to me while I was tuning one there one time. But then when

Baldwin traded their store off to Smith, he was a doorman at Jenkins, I

tuned that for a year, and I tuned for the radio until I gave that up. You

know, you had to stop your job if something went wrong on the radio,

television, or anything. You had to go and fix it right now. And I gave that

up. And the recording stations, I tuned there as long as they had them.

SMOOT: In most cases, were pianos tuned before a person . . . you know, before the

piano was delivered to someone who had bought it?

NACE: Well, most of the time Jenkins did. They always tuned them. Other

20

dealers that I know of, they’d wait till it was moved, because moving it, it

depends on how they sit it on the trucks, you know. The piano, they say

that twelve tons on the small piano and twenty tons on the big ones, grands.

Well, the pressure of the piano sitting on that . . .

[End #3080; Begin #3081]

SMOOT: Orlando, did you have a lot of contact with Margaret Truman? Was she

ever around while you were tuning the piano?

NACE: Not very often. Just once in a while when she was young, around ten years

or twelve. She’d always come in the room and never say much. I knew,

though, she was around. I never had much talking with her. I wish I’d had

more, but I didn’t get to.

SMOOT: Did she ever personally thank you for tuning her piano?

NACE: No, she never talked to me much.

SMOOT: She just used to sort of stand around and watch you, or what?

NACE: Well, she’d come in the room a little while, and then she’d go out again,

just like most children do. [chuckling]

SMOOT: Had you ever listened to her play the piano before?

NACE: No. I listened to Harry. I know one time . . . That’s when we was out at

Lawrence. They had him on television, and he sat down and played the

“Missouri Waltz.” [chuckling] “Well,” he said, “if I’d known they were

going to do this I’d have had the piano tuned,” when he sat down to play on

21

television. Yeah, I remember that. He was just that kind of a man. He was

just plain, and that’s the way he talked. No, Margaret, I never got to talk to

Margaret very much. I wish I had of been, but I didn’t. When she got

older and then she married that man in New York, she was away all the

time.

SMOOT: Did you ever play the piano for Mr. Truman?

NACE: Well, I did some of them. I had two or three pieces. There was one waltz

that if people asked me to play something, I always played that. It was a

very pretty piece. He didn’t go in for that at all. He just . . . oh, he always

just wanted to talk to me a little bit or visit with me while I was there. He

hardly was ever there, only just a few occasions. And him and Mr. Burrus

were very good friends. Burruses were good friends of mine, too.

The military academy in Lexington, is that where he is, back in

Lexington? The military academy, well, I go down there and tune. Each

year they have a big ball there. They have two big pianos. They tune one

lower and the other one up like this, and the orchestra . . . and I went there

and tuned those two or three different years, tuned those pianos for them.

The man that had charge of it is a good friend of mine, had charge of the

music. And then the officers, I go to their homes and tune for them.

SMOOT: What was the name of the waltz that you used to play for Mr. Truman?

NACE: It was a combination. Oh, it slipped my mind. I’m getting old! I had the

22

name. It was three different keys, I know that much: E flat, A flat, and D

flat. The D flat was the one . . . a very pretty part of it. I can’t remember

the name, though.

SMOOT: You stated earlier that you were interested in Mr. Truman. What was it

that made you interested in him?

NACE: Well, the ideas he had about the government and running things and for the

common people. That made me more interested. The common people he

thought about quite a bit, the common people, the laboring man and the

man that don’t have much. He was always interested in the common

people. That’s why we think of Truman. Well, Roosevelt was quite a bit

that way, too.

SMOOT: You said that you had a band that was sponsored by the chamber of

commerce?

NACE: Yeah.

SMOOT: What was the name of your band?

NACE: Independence Cooperative Band, with somewhere around seventy, eighty

members. That was an interesting organization. I had it four years. When

I quit that I went into the auditorium orchestra movement. I turned it over

to another man, and in less than a month it was gone. They wouldn’t

support the man that I turned it over to. We went to state fairs, stock

shows, parades, Labor Day parades and all those things with that band. A

23

busy band. [chuckling]

SMOOT: Orlando, where was the piano located in the Truman home?

NACE: Well, just, you know, go in the front door, then to the left into the room. It

sat there right close in there, right just inside the room close to the door.

Then the stairway was right back of me and went upstairs. That’s where it

was. I think it was there the last time maybe, too. That’s where they kept

it.

SMOOT: And when you got paid after you tuned the piano, who paid you?

NACE: Well, they generally just gave me a check. Mrs. Truman or somebody just

gave me a check for it. I never had to wait on money. [chuckling] It was a

check.

HARRISON: Pam asked about whether a piano would be tuned before it was delivered or

after, and we know the Trumans apparently bought theirs from the Jenkins

Music Company. What was their routine or policy, I guess, of tuning?

NACE: Of Jenkins?

HARRISON: Yes.

NACE: They most generally tuned them before it left the store. That’s the way

they did, right there. But if the customer required checking it, they’d send

a man out to it all right. That’s what I did several times because they’d get

behind with their tuning if they had enough tuners to do all of it. I’d go out

and tune a day or two for them at a time. They tried to get me more time to

24

sales. That’s what they wanted me to do. They paid me a straight salary.

That piano stayed in tune good, though. I never had to change the pitch

much. If a piano is tuned once a year, you don’t have to raise the pitch

much, unless it’s in a dry room. A dry room will affect a piano in a week’s

time. Yeah, in three days you could tell it.

SMOOT: What do you mean when you say “dry room”?

NACE: The furnace heat. That ruins more pianos than anything I know of. They

get them too dry. The sounding boards crack, the ribs come loose, and the

acoustic rim on the outside, sometimes the board will come loose from that

around the edge. And it flattens a board more, and it leaves the crown

where the pressure of the strings is on the bridges. That bridge is supposed

to be this high, a certain height to get you the best tone, between the plate

and the sounding board, and that’s very particular.

This piano I rebuilt down there at Heritage House where I am right

now, I rebuilt that piano. And when we put the plate back in, at the high

end here where the treble is, we left the pressure on the bridge about the

thickness of a dime. That’s about the way it is in the factory. And we took

the bass and put it about the thickness of a quarter, the bass strings. Well,

that will give you the tone quality again in the right amount of pressure.

You get too much, it’s not good; if you don’t have enough, it changes the

quality, especially where the break of the scale is in there. Those things a

25

lot of tuners don’t pay any attention to it. They don’t care enough to put it

back and tighten the screws and let it go. You can tighten the plate down

and make it a little bit more, but you run the risk of cracking your plate,

too, so you’ve got to watch out what you’re doing there.

I had one, the pin block was built into the case on both ends and

clear around the front. We had to saw that block out clear around. And

putting the block back in again in the piano to make the strength there,

what I did, I put blocks into the case on the bottom, strong blocks, and I put

the bolt down through the plate into that block so that it tied it just the same

way again. I didn’t take a chance on the plate breaking the other way. I

had one broken plate, and it’s awful hard to . . . You’ve got to have an old

forge to weld those. You can’t weld them just like you do other weldings.

You’ve got to heat it different.

SMOOT: As a piano tuner, did you ever leave evidence on the piano to indicate when

you had tuned the piano?

NACE: No, I just left my date. And what I did, I’d say, “March here, raised pitch

one half-tone.” You see, we always tuned our pianos. We couldn’t, my

son and I both . . . At the Christian church once he broke forty-some-odd

strings before he quit trying to get it up. They break because they’re too

old, you know. And he told me it just couldn’t be brought up. He’d have

to restring it. But that’s the most we ever did try to bring one up and break

26

it. And he said it just wore him out. But if a piano strings don’t stand it, no

use to wearing your strength out tuning them at all.

SMOOT: So would you put anything else on the piano besides half a pitch? Did you

write anything else on there after you tuned it?

NACE: No, just my name like I did, like that. “Pitch raised half a tone,” and give

the date. I suggested they tune it again within six months. That’s the way I

always do. And that way if they go down a little bit, why, you tune them

next time, then they stay good. Once a year you can keep the pitch pretty

good, but most . . . Just like I say, your piano changes pitch.

Here’s something people don’t think about. When the rains come

in the spring, quite a bit of rain, when the heat comes on the piano goes up

in pitch. The sounding board is a convex shape. It’ll raise up a little bit.

Well, that’ll change the pitch of your piano. Well, now, in August and

July, them hot winds, they’ll lower again. And that’s why the time of year

you tune the piano makes quite a difference. Now, if you tune them when

they’re up, it’s easy for them to go down. But if you tune them when

they’re dry, it’s harder to come up because it takes more pressure to make it

swell and come up. And I always tell them in the wintertime don’t tune it

till after they’ve had their heat on a month or two, you see. It makes the

changes. I watch that pretty close. But people don’t pay much attention to

you. They think it ought to stay in tune for four or five years. That’s the

27

way they think about it, most of them.

HARRISON: You talked earlier about a Steinway, a piano that the Steinways sent the

Trumans or that was signed or something like that, right at the beginning?

It’s our understanding that the piano that’s in the Truman home now,

Margaret’s piano, was sent to the White House when Truman was

president.

NACE: Yeah.

HARRISON: Was there another piano then at the home here in Independence?

NACE: Yeah. Theodore Steinway, I think, gave it to them. They sent it right to

them. I don’t think they paid for it, because they wanted to advertise he has

that piano, you see, a Steinway. That’s the way Baldwin did over to the

library there. They beat Steinway in there. They got a Baldwin in before

Steinway did, and that’s what they advertise, you see. Well, that’s what

they tried to do. Theodore sent one, wrote his name on the top of it:

Theodore Steinway. And I’ve got my name in there too now. [chuckling]

Well, that’s the game, and these men that donate pianos to places is to get

the . . . for advertising is what it is.

HARRISON: So you then tuned . . . During the years that Truman was president, then

you tuned the Theodore Steinway piano in the Truman home.

NACE: Yeah. That’s why every time Margaret would come home I had to go over

there to see if it was in tune. That’s where I come in that time and they

28

thought I was a fellow with a bomb. [chuckling]

SMOOT: And so you said Mrs. Truman would tell you to come around?

NACE: Yeah.

SMOOT: Which gate did you go to?

NACE: Well, the driveway come right in, you know, around where they all came in

and would park all the time. She said no need of me parking across the

street but to come in there and then come right on in the house from there.

But she was watching all right, and that fellow when he came out, he

looked like he was scared. I don’t think he was, but he acted like it.

SMOOT: Orlando, on September 30, 1985, Milford Nace—is he your son?

NACE: Yeah, that’s the last time it was tuned. It was a week or two ago, wasn’t it?

Well, he’s just as good as I am when it comes to tuning. He does a good

job.

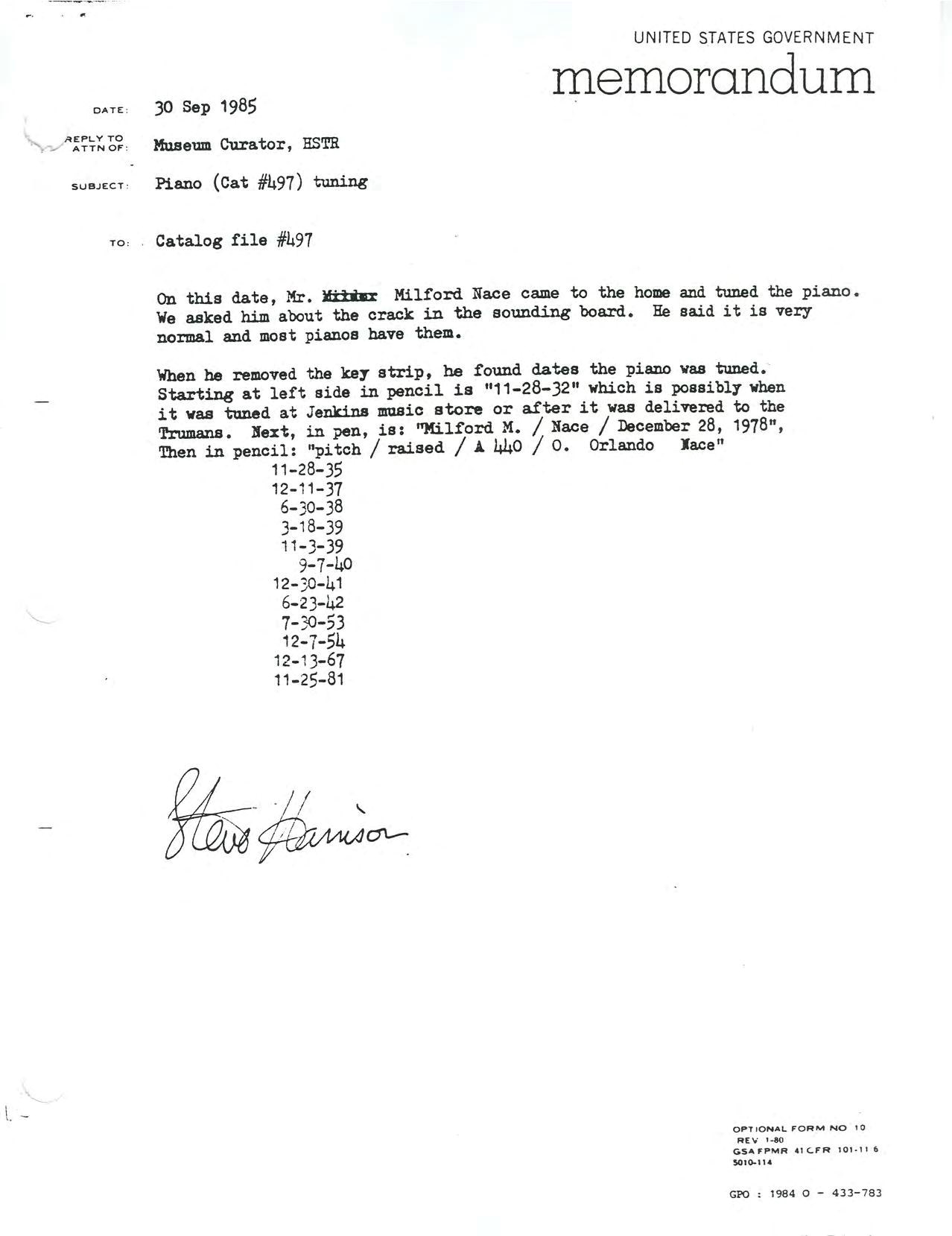

SMOOT: Anyway, when he removed the strip from the piano, there were a list of

dates.

NACE: Well, that was after I tuned it, after they went three years, you see. That

just lifts off on the Steinway. Most of them have got screws underneath.

You just lift that right off and you can spray under there. That’s where

moths start. That’s the reason I said to do that underneath the piano,

safeguard it.

SMOOT: Anyway, the piano was tuned on December 7, 1954, and then it wasn’t

29

tuned again until December 13, 1967—or tuned by you anyway. Do you

remember any of those periods in between there?

NACE: Yeah. Yeah, that’s when I say it went three years without tuning,

something like that. Wasn’t it three years? How long was it?

SMOOT: It was about thirteen.

NACE: Huh?

SMOOT: Nineteen fifty-four, it wasn’t tuned again until 1967.

NACE: It was quite a long time it stood without tuning. Well, that’s when I tuned

it then again, and that’s the time I told them to watch out for moths.

Because I thought moths, it looked like signs of them. They leave a little

fine stuff at first, and then when they eat enough on the hammer you can

see the holes in them, you know. Every piano we tune, every three years

we take the keys all out and everything and clean them again. Tobacco is a

good thing to leave in, just common leaves of tobacco, to keep them out.

We use borax most of the time, borax sprinkled in around the keys on the

pegs. I think of a car: if you let the carburetor go too long, it’s more

trouble to fix than it is to keep it up. That’s the way I think about piano

action.

HARRISON: Did you feel like the Trumans kept their piano up pretty well or . . . ?

NACE: Yeah, they was very good about it, yeah. That was after Harry died.

Margaret didn’t come out to visit as much as she did when Harry was

30

living. She didn’t come out to her mother’s as often, but she always come

quite often for him. She thought a lot of her father. Well, my experience

with them was pleasant I’ve had all those years. I never could say anything

against it at all.

SMOOT: Orlando, on December 28, 1978, Milford tuned the piano. Was there any

particular reason why you didn’t tune it then?

NACE: Well, it might have been that something was wrong with me. See, I lost

my . . . I don’t know what the date was. I was paralyzed for three months

from here down from a fall I got and hurt my back. He had to do tunings

that I couldn’t do. And now, twenty years later I was that way for three

days again. In cases like that, if they wanted them tuned, he’d go and do it

anyhow. The boy who was secretary of the city, when it came to

restringing their piano, he restrung it with brand-new strings and

everything. I couldn’t get to it. Oh, Milford is a very fine tuner. He would

never do finishing work, though.

I did lots of finishing cases. I used my Electrolux for a spray gun. I

bought a spray gun from Montgomery Wards, but I wasted as much shellac

spraying with it as I used. You can’t have a spray gun stop anywhere and

change. Like if you go up there and back it accumulates on there where

you make your change, you know. You’ve got to go on, off, and then

come back on. I use my spray gun with the Electrolux, and I make just as

31

nice a job. I had to cut the lacquer just a little to make it thinner, and I used

more coats, but I did a good job. I’ve got pianos I’ve refinished twenty and

thirty years ago that are still nice, very nice.

SMOOT: So how did Milford come to tune the piano? Did Mrs. Truman call you to

tune the piano?

NACE: No, they called him this time. Yeah, they call him. Well, he’s a Nace, and

they know what my condition is now, you see. Well, Milford’s recognized

just the same as I am, my son, for tuning, but he will not do finish work.

SMOOT: Okay, would Mrs. Truman call you first, or would she just call Milford?

NACE: No, I think the man there that takes care of things, whoever it is, is the man

that did the calling, I don’t know.

HARRISON: But in 1978?

SMOOT: In 1978.

NACE: Oh, ’78? Well, I don’t know then, you see. I don’t know. I have an idea

she did. She was always the one that made the calls. She always did, Mrs.

Truman.

SMOOT: Do you know of any other piano tuner that may have tuned the Trumans’

piano?

NACE: I don’t know of any, because I’d have known it through the association if

they had. They bragged about that. We had some good tuners, but the old

good tuners that tuned that way, the way we do, the German system,

32

they’ve gone on most all of them. Only one or two that I know of left in

Kansas City now. They’ve got an instrument now they tune by the amount

of vibration for the string; they see it and it figures. They don’t listen to

anything; they do it by eye. You see, you take middle C on a piano, it’ll

vibrate 212 times a second, the string will. Well, the one up here is 523-

something, an octave higher, those ratios. Well, on this instrument it’ll

show the 523, and they just . . . till the hand gets to that. Every octave

pretty near doubles. The high end, when I’m tuning, I go by sound waves,

I don’t go by anything else, the ratio, and they just brrt! brrt! [makes

vibration noise]. That’s about as fast. It’s just so fast you . . . and it’s the

smoothness of tone that you go by, you see. The sound waves are that fast

up there. And the fifths in down the middle there, there’s only three and

five seconds. We tune the piano that much out of tune. That’s for people

who don’t know. A piano isn’t in perfect tune. You have to have about

sixty keys in an octave to do that, and you couldn’t handle the key bed.

But we’d make each half-tone equal. I’ll take F sharp, I’ll sharpen it to a

perfect fifth, I have to raise those three little sound waves a second, you

see? I mean, five seconds, three and five seconds. That’s slower than one

second. Well, then I’ll tune G from C. I’ll put a one-second flat, you see?

Then from that the D I’ll put it three and five seconds flat. Well, then I

have a test between the D and the F. If I made a mistake on either one of

33

those strings, I notice it right away, the ratio of the vibration. If it’s like a

tremolo vibrato, like a singer or your finger on the violin string is a certain

rate, and that’s what you go by is your ear. Sound waves. All of our best

tuners use that. The French system we start from A instead of C, but it’s

the same system, only it’s more awkward to get them all divided than to do

it the other way. Mine’s . . . I call it the German system.

HARRISON: You mentioned earlier having to move things off the piano and put them on

the floor.

NACE: That’s what she asked me about.

HARRISON: Do you remember any particular objects that they had on the piano over the

years?

NACE: No, just piles of music and stuff is what it was. I don’t think she had any

other things, only music books and all kinds of books on music and pieces

of music of styles, stacks of it. She taught all the time, and it was just too

much for her to take it off and lay it down. I’d take it off and lay it down.

And then when I got through I’d put it back on for her. Oh, lots of times I

have to do that anyhow. People don’t get them off before I get there. We

have to take them off the piano anyhow, it was always a catchall. I call it a

catchall. [chuckling]

But the people just like I am where I work, where those nurses treat

me, that has an effect on your customer, you see? I do it in a nice way, and

34

I don’t complain or fuss, or make a fuss about it, and it makes them like

you better, that’s all. I have no trouble pleasing the people that way. And

if anything goes wrong, I make it good if something happens. Sometimes

it’s my fault, but if a center pin comes out somewhere and it don’t play, or

a key sticks, why it don’t take long to fix it, and they appreciate that little

favor to come back. And I don’t worry about losing the customer. One

man bragged he tuned seven pianos in a day. Well, you can’t tune seven

pianos in a day. And the man that sold a piano to one of the customers I

tuned afterwards, he sold it, he never did tune the high end at all. All he

told them was “The kid never plays the upper anyhow. What’s the use to

tune it?” [chuckling] Yeah, that’s what she told me he told her. Well, I

went and tuned it anyway. But [unintelligible] all those things.

But I get along fine. I never had to solicit. I never solicited tuning

in all my years. Never did. When I went to Saint Mary’s, Miss Boston

was a graduate from Saint Mary’s and she insisted I go and talk to Sister

Mary Frances—she was the head teacher—and get the tuning from the

sisters there. Well, I said, “I don’t want to start soliciting tuning.” “I’ll go

with you,” she said, “and introduce you.” Well, that’s what she did. I went

over there, and Sister Mary Frances took me up to her own piano, the best

piano in the room, and we talked it over. And she said, “Well, Mr. Nace,

I’ve tried one piano tuner here, and it cost me five dollars to tune it over

35

again. And I don’t like to try that again.” I said, “Sister, I’ll tune your

piano now, and you don’t need to pay me at all. In a week’s time, you try it

out, and if you don’t like it, you don’t owe me a dime.” And she took me

up on it. And she didn’t play fair. She gave me a good piano to tune. And

she tried it all out. And we come and . . . and sixty years of it after that.

And the sisters, when you first go into the academy they wait till

they know you pretty well. There’s a lot of things around, you know, that

somebody who was dishonest he could pick it up, little trinkets. And they

did that for a year or so and then they found out how I was. And when I

quit there, I’d go to the office and get the key and go in and I’d go

anywhere in the building.

One of the teachers, Sister Marie was the head one, when she left

for over on Hardesty, that school, I had to go over there and tune her piano.

She had a big Steinway. And one of the Clinton girls was graduated, she

was a nun then, she had one. Tony Caldwell, a blind man, tuned for her,

and he died. I tuned one for the school and her, but I didn’t want to take all

of them on. I couldn’t do all of them. I turned her down, but I don’t know

what they did for a tuner. There’s just so much you can do in tuning. Two

a day was enough for me. Milford knows. He tuned for the school in

Raytown, in Independence, the churches and things. We’d tune twice a

year, why, you’d come times you get three or four of them a day. It’s two

36

hours you’ve taken . . . two hours each piano, why, that’s eight hours, you

see.

And then when we tuned those eight pianos together for those

concerts, we had to do it at night. One time I tuned half and then he tuned

half of them. But we took pictures of him one night. He was tuning and he

got four more to go. [chuckling] Sitting there in the picture tuning the

piano. So they come to practice the next day, well, you’ve got to have

them in tune. They got them from Jenkins, too. They never was in tune,

all of them.

This one string we start with, and just think, there’s 230 strings

more on the piano. You tune all of them from that one string. Just like

people working together. If you work together, you can accomplish a lot.

If you get all them strings tuned just right, why, look at the music you can

play. You can compare it to people living together. It’s what you can. If

you do your part, it works right in with the rest of it. You have an artist

that does the playing. It’s interesting work. I like it, and I still like it.

SMOOT: Orlando, when you tuned Margaret Truman’s piano, did you sort of treat

this piano any differently than you treated any of the others?

NACE: No. I look at them all just alike. That’s the way I am about people. I’ll

treat you just as fair as I would Truman. See, it don’t make any difference

to me. I do my work the way I know it ought to be done. That’s the point.

37

HARRISON: You mentioned earlier visiting with President Truman in the home one

time, or maybe several times after you had tuned. Was there a particular

room that you would go to?

NACE: No, he’d just come in and sit down over there in a chair for a while in the

room I was tuning and just talk a little while. He didn’t have lots of time,

but there were very few times he was home. Very few times. But he

always would come down and talk a little while when I was there, you see.

Just friendship. That’s what I call it. Just friendship talk.

Well, I’m glad I had the chance of tuning for people like that, you

know. Well, I tuned in Kansas City for the Dietrich family. He was a big

lawyer and everything in Kansas City. He had charge of the Catholic

church and things over there. I went over there and tuned for them, too,

because, well, the Dietrichs was a friend. I rebuilt a piano for them, an

antique piano. They had one they got that was made in England. It had no

iron plates like we have today. They had just plates where they hooked

them on. It never could hold the pitch. It couldn’t hold that much strain.

She had it restrung and everything. I liked the Dietriches. I used to have a

lot of fun with the boys. They had a farm out there in the country, and

sometimes in a big spring and they had stuff sitting in that cold water to

keep it cold. We’d go down with the boys, and oh, we had a good time

eating lunch down there. [chuckling]

38

HARRISON: You mentioned to Pam earlier that you used to have record books of when

you did certain jobs.

NACE: Yeah, we had record books.

HARRISON: Do you know where those are now?

NACE: No, I wouldn’t know. See, my wife is dead that took care of that. No, she

died on my birthday, this last birthday of mine. And the children took the

things that was in the apartment and sold . . . cleared out the apartment and

sold everything. I’ve got a lot of things that I don’t know where they are at

all.

HARRISON: Do you think Milford might have saved those record books?

NACE: Well, they was in a trunk of my wife’s, and she took the trunk to where she

was staying. I don’t know what they did with all them receipts and checks

and stuff. She had that trunk just full of all those things—kept them, you

know.

SMOOT: Can we call Milford and see?

NACE: No, I called Milford. He don’t know what they did with them. See, when

they sold everything off, I didn’t go to see the stuff sold. I’ve lost track of

it. I had boxes of books of history of music and a Bible book—my mother

gave me a Bible—and a lot of other things that I’d like to have had. I don’t

know where they are, even. My daughter, I asked her about them, but it

seems like she don’t know where they are either. Well, I’m getting too old

39

to worry about it now.

HARRISON: Okay, I need to change the tape.

[End #3081; Begin #3082]

NACE: . . . half-cooked. The meat’s dried-out instead of cooked-out. [chuckling]

He’s going to listen now. [chuckling]

HARRISON: Pam is trying not to laugh because I told her not to laugh on the tape. You

can laugh, Pam. I didn’t want her to laugh while you were talking. She

can laugh after you’re done. [chuckling]

SMOOT: Again, you talked about your band being sponsored by the chamber of

commerce. Did Mr. Truman ever come around and listen to this band

play?

NACE: Well, I think he did on the square when he was home. We played on the

west side of the square every Thursday night, and then I played on the

campus for church service on Sunday nights lots of times. Oh, we played

for a half hour before the service, and we did it out of town—well, four

years of it. Of course, we went to the stock shows. We played right beside

the ring two years, and we was in the state fair two years, and I was down

to Marshall once to a ball game with a crowd, and first one place and

another. We was everywhere. And four years of it, we had a good band.

I started out in the church band first, and the church couldn’t

support a band like that, so the chamber of commerce wanted it. We talked

40

to Mr. Owens, he was the secretary at the time, and some of them . . . some

of the people didn’t like it because we was LDS’s and they didn’t want

their children under those Mormons. [chuckling] That’s what they said.

Mr. Owens said, “Well, if any of them’s hurt under those fellows, I’ll be

personally responsible.” That stopped that. But the boys from the

Northeast High School when school was out, they all jumped in. They

come over and joined the band, and we had from eighty-five years old

down to twelve and like that in that band. It didn’t make any difference. If

they played the instruments, why, it was all right.

We had a section of clarinets, a good bunch of them, and our

favorite, the people that couldn’t afford to buy them, at Montgomery

Wards I bought a bunch of clarinets once. There’d be a little crack in them,

they’d come back and repair them and let them have them at the cost, just

merely the cost of it. Pay ten dollars apiece for them or something. Did

violins the same way. It gave them a chance to get them an instrument if

they couldn’t afford it. Well, that group stayed in the organization. They

was there.

SMOOT: Did your band ever play during Mr. Truman’s campaigns, any of his

campaigns?

NACE: I don’t think we did, that we know of. Might have been in some of those

parades, [chuckling] I don’t know. No, I don’t remember, but on the

41

square was the main thing. Well, when the city paid all of our expenses to

the fairs and things, the city paid for the bus and our dinners, although the

dinners were given to us most of the time.

HARRISON: I’m trying to think if there were any other questions. I can’t think of any.

NACE: I don’t know what Mr. Truman’s age was. Do you know?

SMOOT: When? What year are we talking about?

HARRISON: He would have been 100 in ’84. He was born in 1884.

SMOOT: He would have been 100.

NACE: Eighteen eighty-four?

HARRISON: Yes.

NACE: Well, that’s a little bit older than me. I was ’87. Three years difference.

Well, people wonder up there why my mind is as open like it is at my age.

See, so many of the men up there, they don’t say anything, they don’t do

anything, and they don’t know where they are or something else, you

know. I’ll never let myself want to get that way. I play the violin, I’ve

played in the oratorios in the symphony and all that, and I still like to play.

And I made over a hundred violins besides, and they’re in use all over the

world pretty near now, they’ve gone and scattered so. But I like to play

yet, and I keep up on it.

SMOOT: Do you still play the piano?

NACE: No, I don’t play the piano anymore. It’s a shame I quit, but I couldn’t

42

practice five hours a day on the violin and piano, too. That’s what I was

doing, three to five hours a day practicing. That’s where I learned to play.

[chuckling] But I’ve played difficult music on the violin. When I was in

my thirties I really could play good. Now then, to get the curve of the bow

and the exact fingering and all, I have to play a little while before I get into

it. I’ve been keeping up pretty good down here. One woman plays popular

music with me. We play down here. And we’ve got one that play violin,

cello, and piano together. We play more classics, better music. I keep up

with both grades.

I don’t like jazz. I’ve got no use for that real jazz. [chuckling] I

call it real jazz. There’s no theme or melody in it. I think it’s rhythm is all

it is. And the way they act when they’re playing, that knocks me out. Act

crazy the way they jig around. Music that way isn’t for me.

I like the symphony music. It has different kinds of movements in

it, you know, and it gives you good practice. And the positions on the

violin, well, we use mostly about the first six. You have to know where

every finger and what finger makes the notes and all, and jump into them

quick.

SMOOT: I just wanted to ask him, did you know May Wallace at all?

NACE: Knew what?

SMOOT: May Wallace? Did you know her?

43

NACE: No, I never had. George is the only one of the family of boys that I met

besides Mrs. Truman. I knew him when we worked at the planing mills.

HARRISON: Pam asked you earlier about who we call Mother Wallace or Madge

Wallace, who would have been Bess’s mother and who lived in the house

there up until the time that the Trumans returned from Washington. Do

you ever recall seeing her in the house when you were—

NACE: No, I never have. Never have. George is the only one of the rest of the

family I’ve ever met to talk to. And Mrs. Truman. Miss Garr was a good

friend. That girl was good to them, too, but they thought a lot of her. She

was the main cook and household girl there. I liked her, too.

See, I tuned their church piano for them. Well, my days for that is

just pretty near over. I’d like to tune more yet though. The girl that plays

the piano for me for my trio, I’ve took care of her piano since she bought it.

She bought it from a dealer at Blue Springs, and the girl was just learning

piano tuning. She did a pretty good job of tuning, but some of the stems

needed warping to put the hammers hitting the strings. I showed her how

to do it with a match, you know. Well, she didn’t know how to get the

match into the stem. She burned her hand. [chuckling] Kind of tickled

me, and I asked her about voicing, and she didn’t know what voicing meant

yet. That’s making the tone quality of the piano. This one I’ve tuned ever

since she bought it. I’ve tuned the voice so that every key makes the same

44

loudness and all as the other one does, you know, to keep the tone not

harsh, what I call tin-panny. The tin-panny tone that comes quite a bit with

the hammer hitting too hard. You play it so much, and some keys you play

more than others, and that hammer packs more. And when you tune it,

after you get it tuned good, then you voice that hammer with a tool I have

with the felt. And you can ruin a hammer that way, too, if you pick it the

wrong way. But I can make it still sound just the same as them up to it.

I’ve got teachers, if you didn’t tune that way, they’d know it right when

they were playing right away. That’s what Sister Mary Lee . . . They could

always tell if it was my tuning. [chuckling] It’s interesting how people are

pleased with your work. It’s nice to have them feel that way. I appreciate

it.

SMOOT: Well, Orlando, we’ve enjoyed talking with you, and we’re really glad you

let us take up some of your time.

NACE: Well, you pick out what you want to put in the book. [chuckling] We

talked a lot but you don’t need to put it all in there. But I’m interested in

my work. I like it. I like to play.

I want to make one more violin. There’s a secret in toning a violin,

in tuning the woods of a violin. You wouldn’t think it. The air space in

that body of that violin, all of Stradivarius’s best violins, was middle C on

the piano in his time. The middle C in his time was lower than our middle

45

C today. During the First World War we couldn’t get bands together and

everything because some of them was concert pitch instruments, some was

A4-40 and some 4-35 and all like that. Well, they met in France and they

agreed on the standard pitch we have now, A4-40. Well, anyhow, they’re

all that way together now. And after they did that, why, there’s no trouble

to put bands or orchestras together because the instruments are made that

way. But in tuning a piano, if it isn’t up to that pitch, you have to pull your

slides on your horns and things, and it makes it just a little bit thin and out

of tune. Your lip and everything has to make that up. I know more about

music than they give me credit for but . . . because I haven’t got big degrees

all plastered to it. But, you know, I’ve learned a lot in ninety-some-odd

years. And my folks were all musical, the Nace family is. And I enjoy it.

That’s all there is to it. I just enjoy music.

And friendships between the people in music is great. It’s a tie.

Now, the thing that you’re in now, if you like it, you like friends that’s in

the work something like you’ve got. You like those friends; you love

them. Well, that’s the way I look at it in my music work. You see, the

musicians, they just naturally kind of cling together in the way they think

of each other and what you do, not for criticizing the other but if you can

help.

See, this trio, now the piano player quit lessons when she should

46

have kept on. There’s lots of things in music she don’t know what it

means, the signs and stuff, you know. It’s helping her, and the cello

teacher says, “Play with me,” and what they find out in this music I’m

playing is worth more than his lessons was, and he’s advancing by doing it.

You have to play in tune, and there’s a little sign for this and a little sign

for that. The same thing is in singing for breath control. All those little

things you have to consider in music.

I was directing a long time in the choir and orchestra and band, and

I had to know because I had musicians maybe and them there know more

than I did. And if I didn’t . . . On my music, I mark on this music what

that word means, you see, whether it was tempo or expression or what it

was, the little signs, a mark here that I knew what it meant. And if I didn’t

know, they’d ask me the question and I’d feel kind of dumb if I couldn’t

answer it. [chuckling]

The more you’re in your business, you’ll learn as you go, too. You

observe a lot talking to people like me, a rattlebox. [chuckling] A

rattlebox! You haven’t got that on now, have you?

HARRISON: It’s on.

NACE: Well, for goodness sakes! You’re putting all that stuff on there?

HARRISON: That’s all right. Tape’s cheap.

SMOOT: How much money did you say you . . . when you first tuned the Truman

47

piano, how much did you charge?

NACE: Two and a half.

SMOOT: Two and a half?

NACE: Two dollars and a half. [chuckling] I had to tune four pianos to get ten

dollars, and now they get thirty-five dollars for tuning one. Think of the

difference. I’ll have to tune more now. I told my son that. Well, he don’t

have to. He’s got enough ahead that they’re saving money on the money

he has now, you see, on the money market. That’s where I had mine until

they took it all for these hospital bills and doctors. They charge you $2,000

putting that ball on my hip. Think of it! It was probably a couple of hours.

HARRISON: Do you remember how much you charged Mrs. Truman the last time you

tuned, which I think was 1981?

NACE: I don’t think it was . . . At that time it wouldn’t probably have been more

than the fifteen dollars. Well, Milford and I kept it at fifteen dollars for a

long time. And I don’t know what he charged her this last time, whether he

charged the thirty-five dollars. Lots of our old customers he cut the price

ten dollars.

HARRISON: I’m the one who called him, by the way.

NACE: Huh?

HARRISON: I’m the one who called him to come tune.

NACE: You was?

48

HARRISON: I can’t remember, it might have been thirty or thirty-five dollars.

NACE: It was? Well, thirty-five dollars is the cheapest you can get them now,

most of them. That’s what I say, some of his customers he’s seen all these

years, he cut them down to twenty-five dollars. Don’t rope it up too much.

I know Nell Kelly. She was hundred years old lately, and I

furnished the program for the piano and me playing on the program for that

hour. And my birthday had been, you see, ninety-eight, and hers a

hundred. Well, we did it to celebrate her birthday, and it’s called a

“sunshine hour.” And I didn’t furnish the program last week because I

didn’t feel able to do it.

But on that Nell Kelly, I’ve tuned for her ever since she come to

Independence. And she tried to get me and tried to get Milford. Well,

Milford promised he’d go but he couldn’t get to it, so she got another man.

He charged her forty dollars. She said, “Mr. Nace, the high end’s not in

tune at all.” She just, she wants to tune it again. [chuckling] That’s the

way people are.

HARRISON: Thank you again for visiting with us.

NACE: Yeah, well, that’s nice enough. I appreciate it, too, that you think enough

of me that you wanted to do it. I don’t know whether it’ll do any good or

not.

SMOOT: Well, yes, you’ve done very well. You’ve done very well.

49

NACE: But you can pick out what you want to put in there, as far as that’s

concerned.

END OF INTERVIEW

NPS files

piano, 30 September 1985.

NPS

piano, 29 November 1985.