Last updated: February 3, 2022

Article

Olmsted and the United States Sanitary Commission

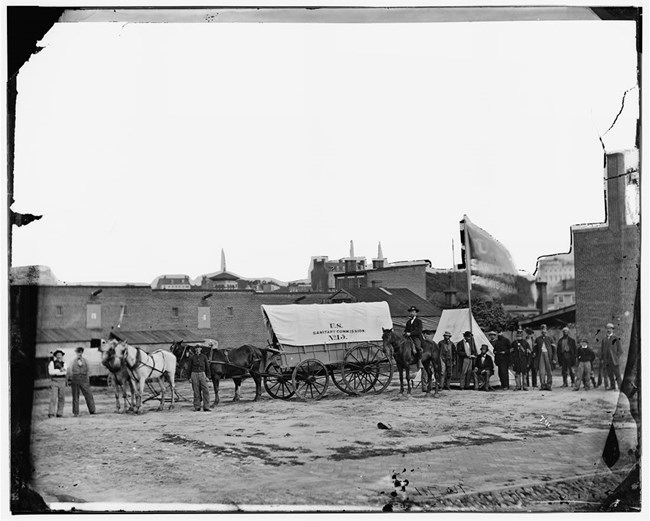

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs, [LC-DIG-cwpb-04159]

Origins of the USSC

The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) grew out of the Women’s Central Association of Relief, an organization formed by a group of affluent New York women. Requiring an experienced leader, the ladies sought the participation of Rev. Henry Bellows, a Unitarian minister.Bellows envisioned a centralized organization which would incorporate local aid societies scattered throughout the North. Drawing inspiration from the British Sanitary Commission, the United States Sanitary Commission would redistribute money and material aid to programs and initiatives that supported the fighting men.

It would also provide invaluable medical and sanitary advice to the woefully unequipped, ill-trained, and understaffed US Army Medical Bureau.

On 13 June 1861, President Lincoln signed an executive order to establish Bellow’s organization. With the USSC now formally established, Bellows sought a competent leader, one who possessed proven administrative experience overseeing large, civilian-based enterprises; his search lead him directly to Frederick Law Olmsted.

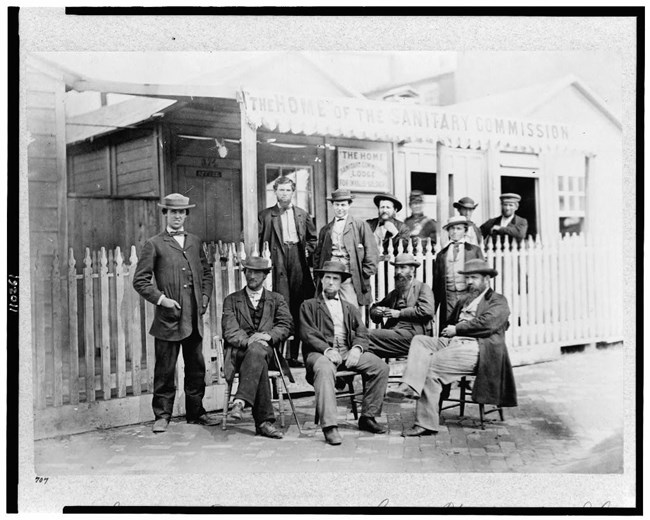

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War, Photographs, [C-USZ62-110261]

An Army in Need

Olmsted proved a superb candidate for the General Secretary of the USSC. His success in designing New York City’s Central Park, one of the largest public works projects of the antebellum era, earned him a national reputation, not only as a landscape architect but also as an administrator. Olmsted readily accepted the offer to head the USSC in 1861.Upon arriving in Washington, DC to inspect twenty army camps, Olmsted found that the troops were shockingly ill-clad, ill-provided for, and living in abject squalor. Officers and soldiers held military regulations regarding sanitary measures in contempt and medicine and medical personnel were in short supply. The army ignored Olmsted’s initial efforts to address the situation.

Conditions improved with the reorganization of the army’s medical bureau and the replacement of Surgeon General Clement Finley with the progressive and cooperative William Hammond. These developments arrived just in time—Gen. George B. McClellan was about to begin his Peninsula Campaign in the springtime of 1862.

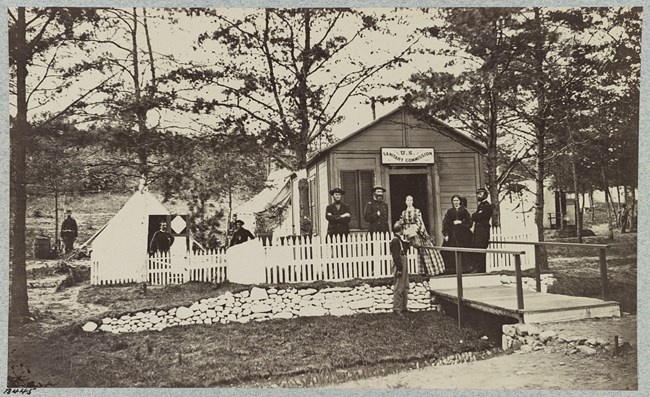

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs, [LC-DIG-ppmsca-33753]

Aid for a Nation in Crisis

The Peninsula Campaign promised to yield thousands of casualties. Over 100,000 troops were transported to the Virginia peninsula in preparation for the Union’s major offensive to subdue the Confederacy. Beginning with the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, soldiers by the hundreds streamed into USSC hospitals. The subsequent Battle of Fair Oaks and the Seven Days’ battles brought more casualties.The indefatigable Olmsted rose to the challenge, supervising medical staff, distributing supplies, and personally treating soldiers who suffered from battlefield wounds. By the close of the campaign, which ended in Union retreat, Olmsted estimated that the USSC treated upwards of 8,000 sick and wounded soldiers. Confederate prisoners of war made up approximately one quarter of the Fair Oaks casualties treated by the Commission.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Civil War Photographs, [LC-DIG-ppmsca-33752]

Olmsted’s Impact

Olmsted served with the USSC until after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863. By that time, his relationship with the organization’s executive committee, which sought to curtail expenditures and exert greater control over his day-to-day operations, became acrimonious. Eventually, physical and mental exhaustion compelled Olmsted to resign as General Secretary on September 1, 1863.Thanks to Olmsted’s impressive administrative and leadership skills, the USSC successfully aided thousands of soldiers. Using the same logical, analytical approach he applied while managing the Central Park project, Olmsted developed a series of procedures and protocols that enhanced USSC operations: hospital ships were divided into wards to allow troops suffering from contagious diseases to be quarantined; shipboard operations were organized into two “watches”; meals were served and medications were dispensed at specific times; casualties’ personal information, such as their units, ranks, and demographic data, was collected and stored in hospital directories that aided report writing, record keeping, and other administrative tasks; and triage stations were established to sort out the flood of wounded before they arrived at hospital ships. Olmsted also advanced the organization’s agenda by requesting that prominent people travel to various cities and towns to promote the USSC’s mission.

By the war’s end, the USSC, in addition to treating many thousands of wounded soldiers, worked with 286 local aid societies, from which it obtained $15 million in supplies and $5 million in cash donations. Furthermore, the Commission conducted 1,482 camp inspections, advised army medical staff, and established a veterans’ bureau to aid returning soldiers. Olmsted’s administrative tenure bequeathed a legacy that informed USSC operations for the remainder of the war. The USSC was a remarkable achievement—one that gave Olmsted great pride and satisfaction.