Last updated: September 4, 2025

Article

Old Fort Raleigh State Park

In short when a visitor enters the gates of Fort Raleigh, I want him to be mentally transported back three hundred and fifty years

Fort Raleigh went through several different iterations before the National Park Service (NPS) acquired the property in 1941. It was a gathering place, private park, and a state park. As the park progressed from a simple wooded grove, then a set of stone pillars commemorating the colony’s place in history, and later as a reproduction village acting as a backdrop for the “Lost Colony” play, the grounds have changed in that time as well. The story of Fort Raleigh before the NPS is a tale of wonderous ideas and financial shortcomings.

Commemorative assemblies started at Fort Raleigh in 1880. In 1894 a group of historically minded North Carolinians expatriates living in and around Baltimore, MD attempted to bring attention to North Carolina’s claim to English colonization. By the latter half of the 19th Century, Roanoke Island had been relegated to the background of American colonization. Jamestown, Virginia prepared to celebrate its 300th Anniversary and the Pilgrims of Massachusetts became the beacon of American religious freedom in early American history. Professor Edward G. Daves led the group, soon to be named the Roanoke Colony Memorial Association (RCMA), to bring attention to the site.

Commemorative assemblies started at Fort Raleigh in 1880. In 1894 a group of historically minded North Carolinians expatriates living in and around Baltimore, MD attempted to bring attention to North Carolina’s claim to English colonization. By the latter half of the 19th Century, Roanoke Island had been relegated to the background of American colonization. Jamestown, Virginia prepared to celebrate its 300th Anniversary and the Pilgrims of Massachusetts became the beacon of American religious freedom in early American history. Professor Edward G. Daves led the group, soon to be named the Roanoke Colony Memorial Association (RCMA), to bring attention to the site.

In 1921 the North Carolina Department of Education arranged to shoot a film about the Lost Colony. With the backing of the RCMA, the film would stage the action on the site of Fort Raleigh. This silent film would be viewed by countless North Carolina students and stay in circulation until the 1960s. Nine years after the film, in 1930, RCMA accepted two pillars of alternating brick and stone layers, from the U.S. Government. Each pillar sported an engraved stone shield that commemorated Sir Walter Raleigh, Native American guide Manteo, Virginia Dare, and the rest of the Lost Colony. The pillars were placed on the southern edge of RCMA park’s borders, along the local highway.

The 1930s would see a flurry of activities and ideas in developing the park. Grandiose monumental designs, fountains, recreations of the village and ships, a living history Native American village populated with Cherokee from western North Carolina, and a pageant were debated, but each of these grassroot ideas floundered for the lack of funds.

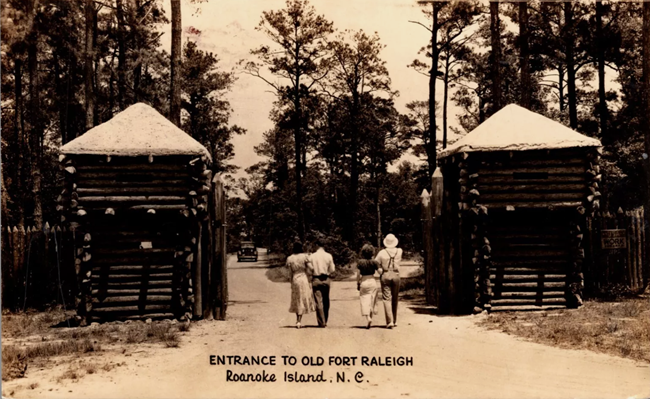

As part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s programs to pull the country out of the Great Depression a series of government entities attempted to revamp the areas stagnant economy by creating the recreated English village nearby the “restored” old Fort Raleigh. This time, with the combined funds of Local, State and Federal agencies and RCMA’s approval, Old Fort Raleigh State Park became a reality.

As part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s programs to pull the country out of the Great Depression a series of government entities attempted to revamp the areas stagnant economy by creating the recreated English village nearby the “restored” old Fort Raleigh. This time, with the combined funds of Local, State and Federal agencies and RCMA’s approval, Old Fort Raleigh State Park became a reality.

But even as it was being created the Old Fort Raleigh State Park was in conflict. After deeding the land to the state for the park’s creation, RCMA, among other concerned parties, worried about the over commercialization of the site. Plans proposed for reproduction ships and a native village site were in the works, while tourist camps and hotels sprung up just outside the park’s walls. At the height of the Great Depression, it was difficult for the state to staff the site. All parties hoped that the site could be transferred to the National Park Service. But there was a catch: the NPS wanted to remove the buildings, before it would accept the land transfer.

National Park Service officials were hesitant to absorb the site for a variety of reasons. Until an archaeological dig proved the authenticity of the old fort site, many felt the fort was misidentified as 16th Century. Further research proved the English did not construct log cabins at their other colonial sites, and that the first accepted log cabin in America was built in 1639 by Swedes in modern day Delaware. The Park Service was also reluctant to partner with The Lost Colony play for a variety of logistic and maintenance issues. But in April of 1941 the National Park Service took over the old Fort Raleigh site. What happened to buildings?

There are still remains of the old Fort Raleigh State Park to be seen today, if you look hard enough. Beside the pillars at the Manteo Waterfront, pathways and trails are still in use by today’s park. The tops of the watchtowers that stood guard at the park entrance are in the park’s storage area. At least one of the state park buildings remains standing, moved off site and is now used as a private home. But the most obvious remains are those of the old fort itself, that has remained at the center of these various parks since 1894.