Last updated: July 22, 2021

Article

Ohio's Prehistoric Past

Ohio has an incredibly rich history. For more than 14,000 years humans have lived in the region between Lake Erie and the Ohio River, now known as Ohio. Early Native American groups traveled across the landscape and hunted, gathered, and farmed in the area. Historic Native American tribes including the Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandot, Miami, Ottawa and Seneca called the region home prior to and after pioneers entered the region in the late 1600’s. The remains of even earlier inhabitants are present in Ohio’s landscape, visible to us through the preserved and reconstructed earthen mounds at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. Furthermore, the archeological remains of where these early people lived are scattered throughout the state.

We learn more about Ohio’s prehistoric past through the work of archeologists. An archeologist’s goal is to learn about how people lived in the past by examining the material culture that past peoples left behind. Material culture, better known as artifacts, can be broken pottery, stone tools such as arrowheads, food remains such as seeds and nuts, and decorative items like jewelry and trinkets. Artifacts also give archeologists clues to how cultures and peoples changed over space and time.

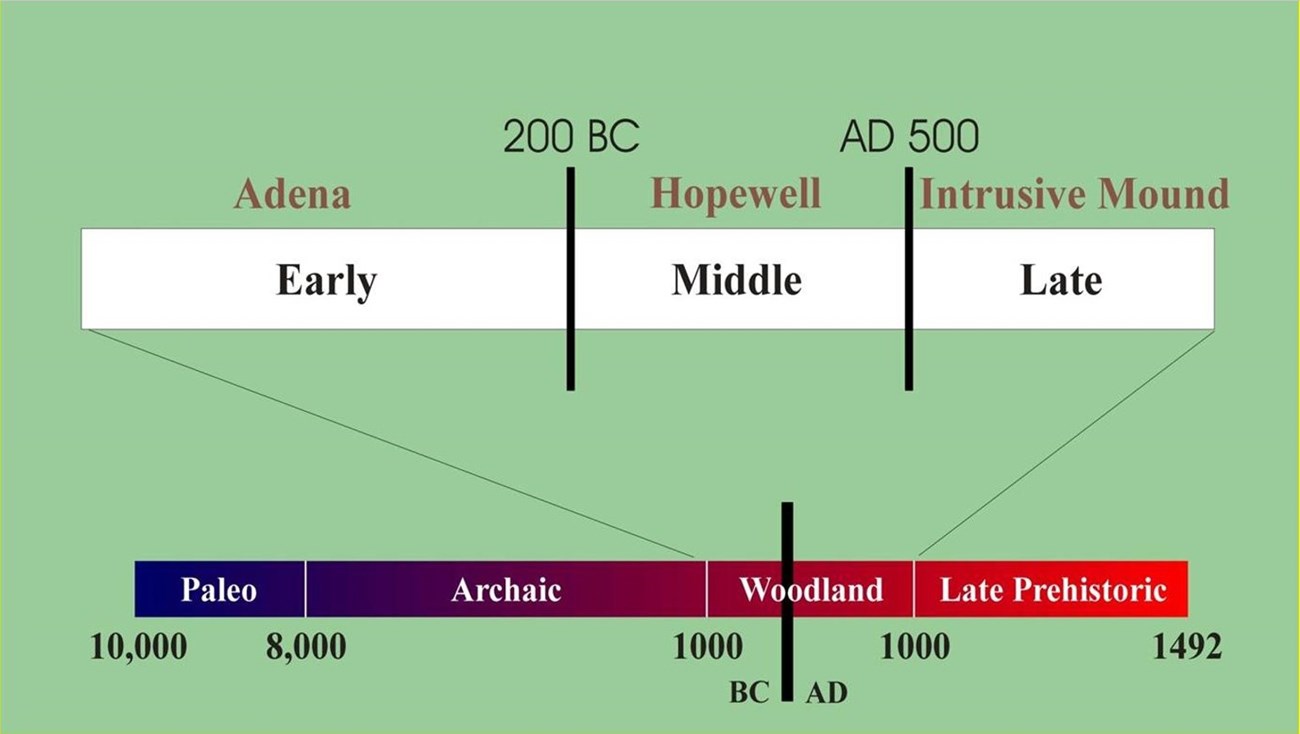

In this reading you will learn about Prehistoric Ohio, the history of Ohio prior to western expansion of the American colonies in the late 1700’s. Archeologists studying the Eastern Woodlands divide the 14,000 year history of Ohio into four major time periods based on artifacts and other scientific evidence recovered from archeological excavations. These time periods are: Paleo-Indian (12,000-8,000 BCE), Archaic (9,000 -1,000 BCE), Woodland (1,000 BCE-CE 1000) and Late Prehistoric (CE 1000 -1650). While these time periods serve only as basic guides to what happened in the past, each period is uniquely defined by changes in day to day life and material culture. We are going to focus on the woodland period and specifically the middle woodland period.

NPS

The Woodland Period in the Ohio Valley

(800 BCE - CE 1000)

The Woodland Period in Ohio is defined by people settling into communities, the beginning of agriculture, and the building of massive mounds and earthworks. Mounds are usually conical and singular while earthworks are combinations of mounds and walls organized into geometric shapes and make up large complexes covering acres of land. During the Woodland Period Native Americans built thousands of mounds and earthworks in the Ohio Valley. While the mounds they constructed were often used for burials, it is also believed that the large geometric earthwork sites they built represented places of ceremonial gathering for the community. A handful of earthworks can still be seen today.

The Woodland Period is subdivided into Early, Middle, and Late periods based on different ceremonial traditions and material culture.

NPS/S.Patrick

Early Woodland Period: about 800 BCE BC to CE 500

The early Woodland culture in Ohio is known as the Adena. The Adena culture lived in large habitation sites near waterways. They hunted and gathered like their Paleo-Indian and Archaic ancestors. Adena habitations sites were larger than Archaic sites and were semi-permanent, meaning the Adena stayed in one place for longer periods of time than the Archaic peoples. Their shelters were constructed from wood covered with mud, clay, and grass.

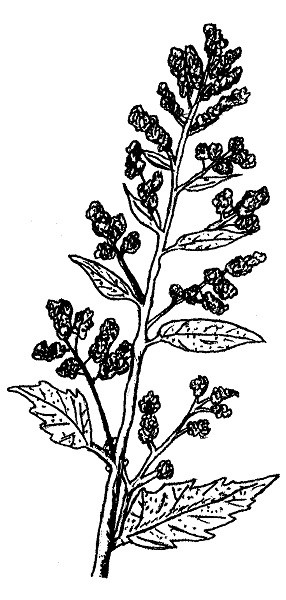

In addition to foraging for local nuts and berries, the Adena began to plant native plants including goosefoot, knotweed, sunflower, sumpweed, maygrass, tobacco, and squash. They were the first gardeners in the region. The Adena also began to perfect their pottery making. While Adena pottery was still basic, it was more decorated and more durable than Archaic pottery. Pottery was used for storing gathered plants that were an important part of the Adena diet.

During this time, American Indian groups built large cone-shaped mounds up to 63 feet high. The mounds were mostly used for burials but not always. Accompanying these mounds were sacred spaces created by piling up dirt in low earthen walls in the shape of circles around the conical mounds. These spaces served as monuments, ceremonial centers, and boundary markers. Funerary artifacts including shell beads, copper antlers, copper bracelets, and tubular pipes accompanied the burials. A sacred circle, a low circular wall made of piled and packed earth and sand, and a low ditch surrounded a completed mound or a circular ring of paired posts. These paired post structures were used for rituals and ceremonies.

NPS/S.Patrick

Middle Woodland Period: about 1-400 CE

The Ohio Hopewell continued the tradition of mound building but took it to a more complex level. There were many groups of people that lived all over the eastern half of the United States. We call the people who lived in what is now present-day Ohio, the Scioto Hopewell. In addition to conical burial mounds and sacred circles, this culture was known for building geometric earthworks hundreds of acres wide. These earthworks were shaped like circles, squares, and octagons. More than a dozen of the largest earthworks and mound centers are located in Ross County, Ohio. At one point in time there were over 600 Hopewell earthworks in the State of Ohio. The embankments or walls of these Hopewell earthworks were as tall as 10-12 feet and enclosed as many as forty mounds each. Not all Hopewell earthworks contain burials. Some sites contain no burial mounds, for instance, Hopeton in the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park or the Newark Earthworks located in Newark, Ohio. These sites do not contain burials but are significant because they have very strong lunar and solar alignments. This means that when the sun rises or sets on specific days of the year, you could stand in one passage of the earthwork and watch it pass directly through a passage opposite from you. The Scioto Hopewell paid close attention to the movement of the sun, moon, and stars and seemed to have ceremonies to accompany the changing position of these heavenly bodies.

NPS/S.Patrick

Based on the large amount of objects buried with the dead and the size of the earthworks and mounds, we know that Hopewell earthwork centers must have been built by many groups of people coming together. In many cultures around the world, such large scale public works projects were overseen and controlled by a class of elite rulers, many of whom passed their status to their children. In Hopewell society, however, little evidence of a ruling class has been found.

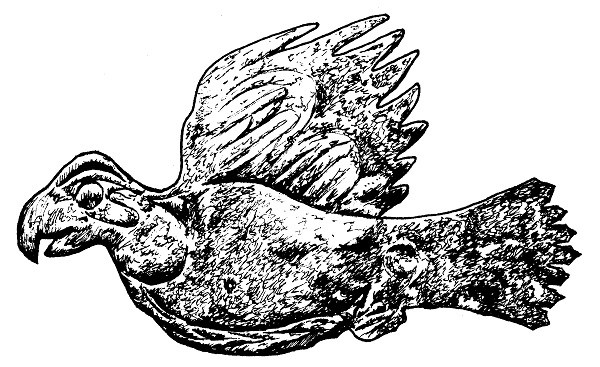

The Scioto Hopewell created artifacts from beautiful materials that were not local to the region. Using rivers and trails for transportation, the Scioto Hopewell brought exotic materials to Ohio. They carried copper from the southern shore of Lake Superior, silver from east central Canada, obsidian from what is now Yellowstone National Park in western Wyoming, mica from the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, and shells from the Gulf of Mexico. These raw materials were expertly carved and molded into the shapes of birds, mammals, reptiles, humans, and dozens of other forms. It seems that the natural environment played a significant role in Scioto Hopewell religion and art.

NPS/S.Patrick

When not attending group gatherings at earthwork centers the Scioto Hopewell lived a life of hunting, gathering, and farming. Their settlements were scattered throughout southern Ohio. Each site had just a few homes constructed by setting logs upright and covering the spaces between with bark or a mud and grass mixture called daub. Nearby plots were sown each spring with seed-producing plants such as goosefoot, sunflower, knotweed, little barley, sumpweed, tobacco, and may-grass. By studying their middens, what archeologists call trash piles, we have learned that these people relied on a variety of starchy and oily seed-bearing plants and nut trees, evidence that they foraged for nuts and other seed bearing plants. Bountiful garden harvests helped the Hopewell survive the winter and lessened the need to move to different camps. They stored these food sources in pottery that was thinner and more decorated than Early Woodland vessels.

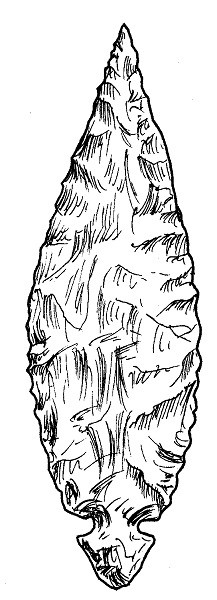

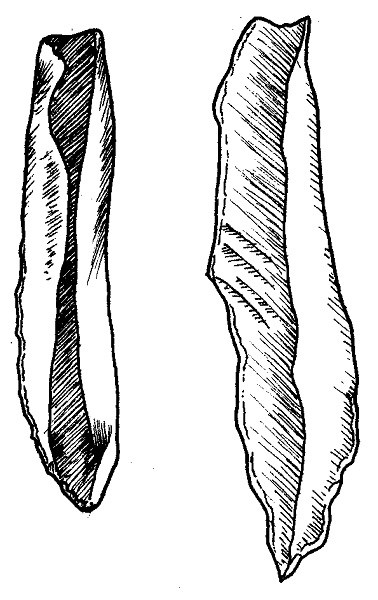

The Scioto Hopewell hunted deer, rabbits, raccoon, and other local animals using a spear and atlatl. Hunting methods had not changed much since the Archaic period. The Scioto Hopewell developed another useful stone tool referred to as a bladelet. A bladelet is a thin piece of flint similar in shape to a razor blade. Some obsidian bladelets of the Hopewell are sharper than modern surgical steel. These artifacts were used to skin animals for clothing, cut meat, and to carve wood and other materials. Bladelets were a prehistoric multi-purpose tool.

By A.D. 400 Hopewell communities were using their earthwork centers less and less, and the use of exotic raw materials in ceremonies was declining. People began to move away from the earthwork centers and their material culture became less extravagant. While descendants of the Ohio Hopewell lived on, focusing even more on growing food in large garden plots, their cultural priorities changed. It is unclear why the Hopewell culture declined so abruptly but it could be due to social changes, population changes, or change in climate. Though the practices of the Scioto Hopewell culture period ended, the same people continued to occupy the area.

Late Woodland Period: about CE 400 to 1000

The end of mound-building marks the beginning of the Late Woodland period. During the late woodland period, people in the region began to move around more so than they did in the Middle Woodland period. Their base camps are smaller and less permanent than those of the Hopewell. The Late Woodland people continued to grow native crops such as goosefoot, sunflower, knotweed, sumpweed, tobacco, may-grass, and squash in small gardens and added another crop that would later be important to life in the region; maize, better known as corn.

During the Late Woodland period, people used the bow and arrow. Stone tools shifted from large spear heads to small arrowheads used to hunt deer and smaller animals. The chert, a type of stone used to produce these arrowheads, was not as high quality as Hopewell material. Pottery remained a common artifact in the Late Woodland period. Late Woodland pottery is commonly thinner and includes other materials or tempers (i.e. shell, sand, or grit) which helps a pot resist shattering in higher heat.

The Late Woodland people buried their dead with less ceremony than the Hopewell. The dead were buried in middens or storage pits, sometimes stone mounds were constructed. Some groups in the Late Woodland period buried their dead in the tops of Hopewell mounds. These groups may have been attempting to connect with the Hopewell that came before them. This group, known as the Intrusive Mound culture, had a very different set of artifacts than the groups appearing to descend directly from the Ohio Hopewell. Such artifacts include Jack’s Reef Corner Notched arrowheads, and a beaver tool and antler that possibly came from New York.