Last updated: November 2, 2021

Article

Nunamiut: The Caribou People

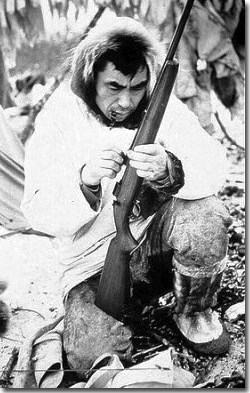

Helge Ingstad photo

“Caribou meat is our meat since I was born. I was raised with it. The skin was my clothes. The meat was my diet and the broth was my drink… Without caribou meat, what would I eat...?”

Rachel Riley, Nunamiut Elder

In Northern Alaska, people and caribou have lived in a close, intricate relationship for at least 11,000 years. Caribou have been vitally important for the survival of all native people whose homelands are now partially encompassed by Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve—Nunamiut Eskimos, Eskimo people of the Kobuk and Noatak Rivers, and Koyukon Indians.

For some tribes, caribou is just part of a diet which also includes other game, fish and marine mammals. But for inland mountain people—the Nunamiut Eskimos—caribou is by far the single most important food source. Since a time far beyond memory, Nunamiut people have eaten meat, fat, and many other parts of caribou and have sipped broth made from caribou meat and bones. Caribou skin clothing—parkas, pants, boots, socks and mittens—has protected them from the arctic cold. They have slept under caribou skin blankets and have sheltered in caribou skin tents. Caribou hides have also provided rawhide line for making snowshoes and sleds. And sinew from caribou tendons, in single or braided strands, has been used to make nets to catch ptarmigan and fish, as lashing for hunting tools, and as a strong and durable thread.

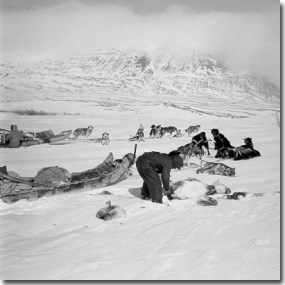

Photo Courtesy of the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, Ward W. Wells Collection.

For Nunamiut people, the importance of caribou extends far beyond the material realm. This animal is at the foundation of their history; it pervades their daily life; and it is a symbol of their unique inland culture. Caribou hunting is pursued with passion and pride, as an endeavor requiring great skill, and it is underlain by deeply held spiritual beliefs. Today, as in the past, caribou symbolize what it means to be Nunamiut.

In historic times, reliance on migratory caribou herds dictated a nomadic lifestyle. It also made the stories and teachings passed down through generations crucial for success in hunting and for survival in the challenging arctic environment. Beginning in childhood, Nunamiut people acquired a sophisticated knowledge of caribou behavior and ecology, they learned every detail of the landscape, and they came to understand the vagaries of arctic weather. They also devised a complex array of hunting methods, such as the construction of human-like stone figures (iñuksuit) to help direct or funnel caribou over many miles into corrals, lakes or rivers where hunters waited with spears or bows and arrows.

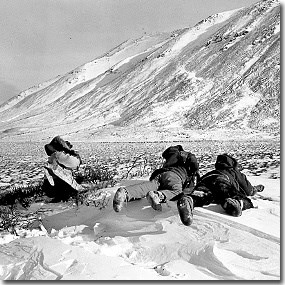

Photo Courtesy of the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, Ward W. Wells Collection.

Modern life has changed from earlier times, when Nunamiut Eskimos moved their encampments from place to place to intercept caribou migrations. Since the 1950s, they have lived in the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, which is on a major migratory pathway. However, an intimate knowledge of caribou is still essential for Nunamiut hunters, who travel widely by snow machine and hunt with rifles, either alone or in small groups. The people continue to wear beautiful caribou skin boots, socks, and mittens, and they sleep on caribou hide mattresses in camps. They have created a new art form—the caribou skin mask—which provides an income for some village families. And most importantly, caribou meat and fat are still essential as staple foods for today’s villagers.

The braid of life between caribou and people remains unbroken.

NPS/Jeff Rasic

Caribou Hunting

Throughout the history of Nunamiut Eskimos living in the Brooks Range, success in caribou hunting was critical to survival. People frequently moved their encampments to follow the caribou and intercept their migrations. When caribou were plentiful, there was meat and fat in abundance, hides for clothing and shelter, sinew for thread, and rawhide for lashing. But when caribou were scarce, the inland Eskimos could face hardship, hunger, and even starvation.

Over the passage of many generations, Nunamiut people closely observed the migratory patterns of caribou and learned every detail of the landscape. They understood how local topography channels the long skeins of caribou coming from the north in fall or the south in spring. And they came to know caribou so well that they could enter the animals’ minds, predicting where they would go and how they would react in a wide range of circumstances.

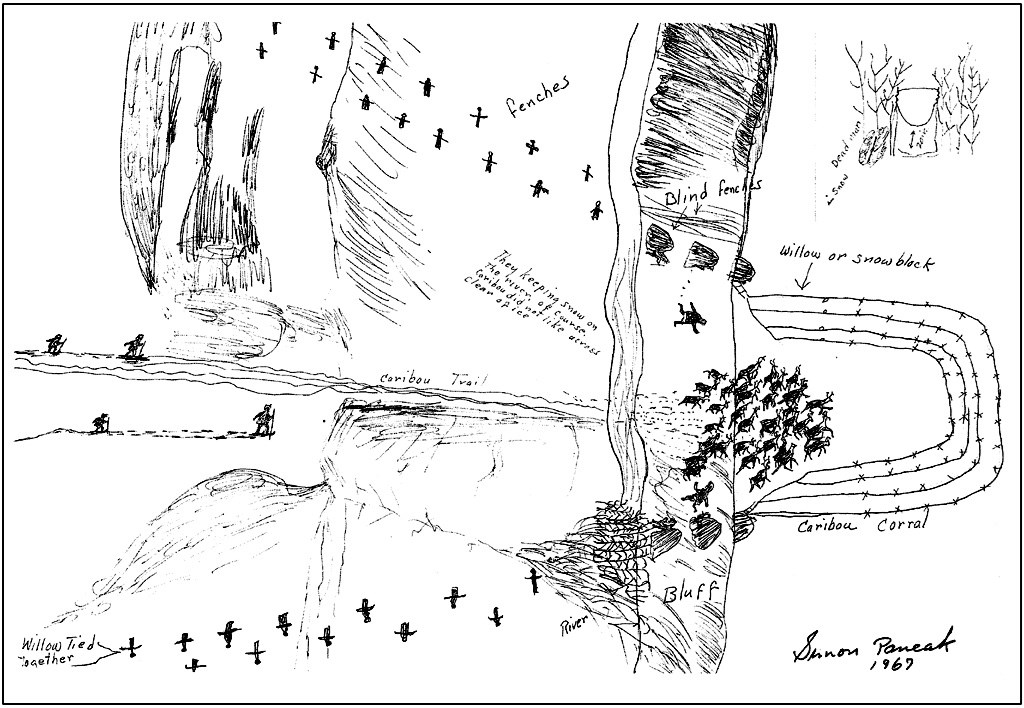

Hunters learned that the movement of caribou could be influenced by something tall, erect, and human-like on the open tundra. Using this knowledge, they made stone people (iñuksuk), by standing elongated stones on end or by piling up rocks and topping them with willow branches and bits of cloth that fluttered in the wind. Nunamiut Eskimos arranged these scarecrow figures in two gradually converging rows, sometimes up to five miles long. When a herd of caribou approached, the iñuksuit (plural for iñuksuk) helped to funnel them into a lake, a river, or a corral where they could more easily be killed.

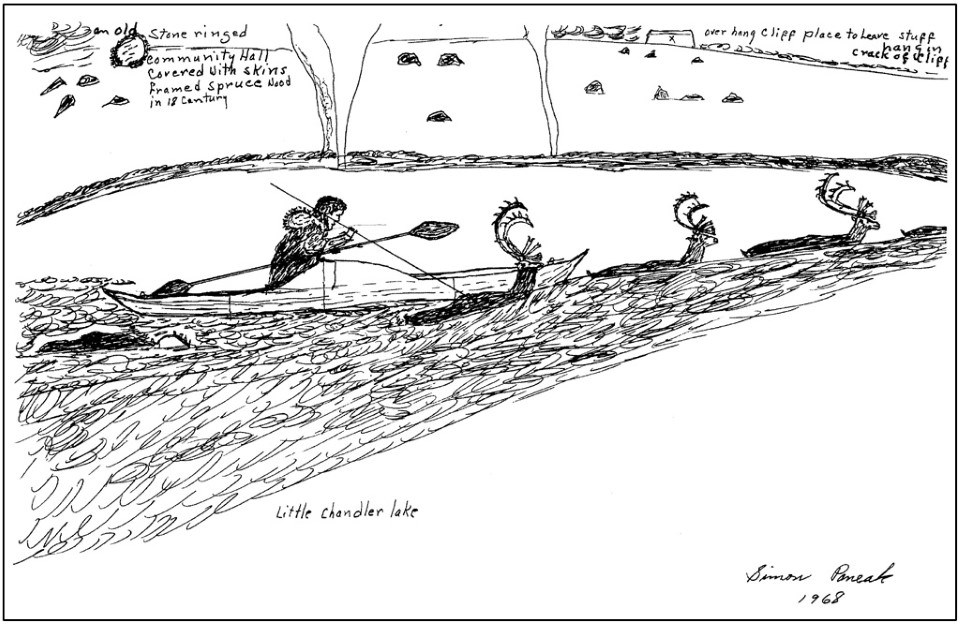

Simon Paneak illustration

In winter and summer, the larger bands broke up into small family groups that dispersed widely, and Nunamiut men hunted caribou individually or with a few companions. Then, during the spring and fall caribou migrations, bands came together for the very important caribou drives. In places known for seasonal concentrations of caribou, the people or their ancestors had built lines of iñuksuit.

As a herd of caribou approached, women, children, and elders who were not hunting moved in behind the animals, carefully driving them between the lines of scarecrows, and then urging them along until finally the herd entered the water.

This was the moment the hunters had been waiting for—sitting in kayaks tucked out of sight against the lakeshore or under a concealing riverbank. Their specially designed inland kayaks (qayaq) were long and narrow, built for maximum speed. Once the caribou started swimming, hunters swiftly paddled after them, came up alongside, and killed the animals with spears.

Simon Paneak illustration

Importantly, caribou do not sink like most other animals because their coats are made up of hollow hairs, with tiny pockets of air providing buoyancy. Hunters could get large numbers of caribou and then tow them ashore. Then everyone in the camp worked to butcher the caribou and preserve the meat, either by drying it in the open air or by freezing.

In areas without suitable lakes or rivers, the drive line ended in a corral—a U-shaped fence made from willow poles and branches. Large rawhide nooses were hung in gaps between the willows, and caribou became snared as they tried to escape through the openings. Hunters then killed the animals with arrows or spears.

Over the past century, these traditional weapons gave way to rifles, and Nunamiut hunters used the old drive lines less and less. Eventually the people left their nomadic camps and settled into the village of Anaktuvuk Pass. The communal drives ended before 1900, but in 1944, a shortage of bullets during World War II spurred Nunamiut hunters to resurrect the caribou lake hunt. Like a dream from the past, an ancient tradition was played out one last time as men in qayaqs, armed with homemade spears, sped across the water to intercept the swimming caribou.

Tags

- gates of the arctic national park & preserve

- alaska

- alaska native

- alaska native history

- gates of the arctic national park and preserve

- anaktuvuk pass

- brooks range

- indigenous heritage

- native american heritage month

- caribou

- arctic

- arctic culture

- subsistence

- traditional knowledge

- people

- native stories

- culture