Last updated: January 9, 2025

Article

Guidebooks and Accessibility: Tools By and For Disabled Visitors, Past, Present, and Future

By Ellie Kaplan/NPS Park History Program

How do you plan for a trip to a national park? Do you check the visitor center’s hours? Do you track the weather to help you pack appropriate clothing? Whether or not you are disabled, we all benefit from having more knowledge about a park’s accessibility. For disabled people, we may need more information, like:

- Will the bathroom stalls be wide enough for my wheelchair?

- Will information pamphlets be available in Braille?

- Will there be a place to buy snacks if my blood sugar drops?

Disability advocates and nondisabled allies have a long history of sharing information that makes parks more accessible and democratic spaces.

Background

Since the late eighteenth century, travelers have used guidebooks in their trip preparations.1 Yet mainstream guides often did not supply adequate information for all visitors. So, specialized guides became necessary. For example, the Green Book was published during the 1930s to 1960s. It let Black travelers know about safe accommodations and businesses that would serve them respectfully in the era of Jim Crow laws and anti-Black racism.

Some disabled visitors have also needed more specialized information than a standard guidebook provided. Thanks to the disability rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the general public started to recognize the barriers encountered by people with disabilities. This growing awareness of the needs of disabled people filtered into the realm of guidebooks.

In the paragraphs below, you’ll learn about three guidebooks written by and for visitors with disabilities traveling to National Park Service sites. Over the last fifty years, these guidebooks have demonstrated the power of preparing disabled visitors with good information so they can make decisions for themselves. They also confirm that a park cannot be truly accessible without readily available detailed information.

Click on the image for a 508-compliant version of the page.

National Park Guide for the Handicapped - 1971

In 1971, the NPS published the first accessibility guide of its kind: The National Park Guide for the Handicapped. The booklet conveyed “the conveniences and the obstacles” a disabled visitor was likely to encounter at almost 250 NPS parks, monuments, and other sites. 2 In the introduction, NPS Director George B. Hartzog Jr. acknowledged the Park Service needed to do significant work to make its parks more accessible. But he believed that providing this information would be a good first step. He wrote, "In this booklet we issue a specific invitation to the handicapped. We hope you will accept it." 3

A common theme in this guidebook was access “by request” or “with assistance.” For instance, at Wolf Trap Farm Park for the Performing Arts in Virginia, wheelchair users could only access the Filene Center through a special ramp after talking to the box office. Wheelchair users could not use the same entrance as non-disabled visitors. At other sites, the guide suggested that a disabled visitor could manage some barriers, such as a curb or a few stairs, “with assistance.” This approach stands in contrast to today where accessible design requires independent navigation.

National Park Service

Today, Universal Design guides most design choices in the NPS. Developed in the 1980s and 1990s, Universal Design goes beyond compliance with laws and building codes. Instead, it tries to be inclusive of peoples of all different body types and abilities. It is defined as “the design of products and environments to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design.” 4 Curb cuts in sidewalks are an example of universal design. They facilitate the movement of people who use wheelchairs, walkers, or strollers, right alongside those who do not use such mobility aids. Having captions on all videos, rather than turning them on and off depending on the audience, is another example. Captions can benefit many people, including people who are D/deaf or hard of hearing, individuals with intellectual or developmental disabilities, English-language learners, children, and more.

Photo by Ellie Kaplan

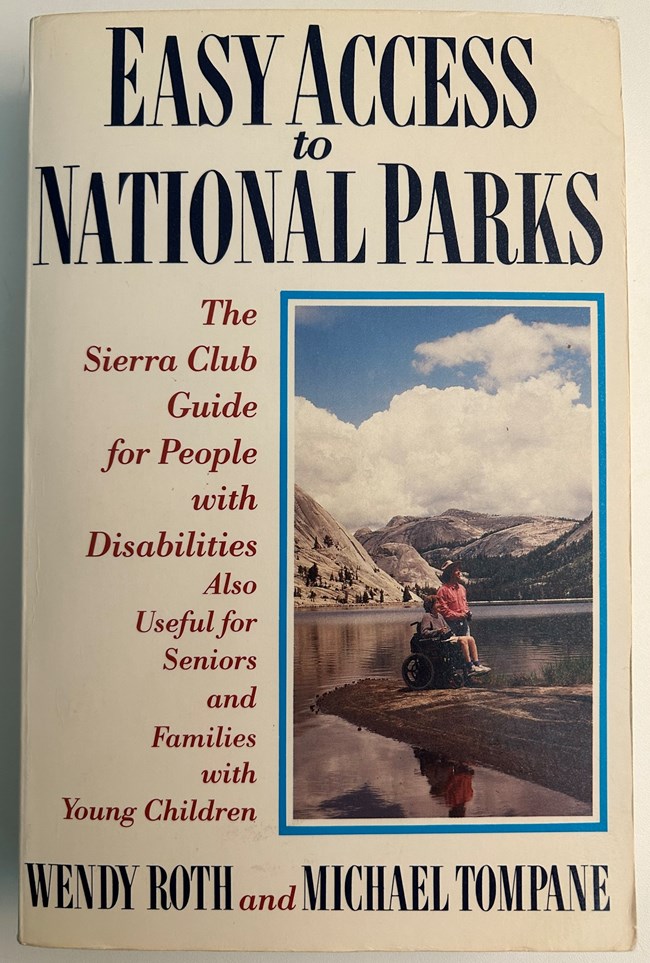

Easy Access to National Parks - 1992

In the late 1980s, Wendy Roth, a disabled woman, and her non-disabled husband Michael Tompane visited three national parks: Bryce Canyon, Zion, and Grand Canyon. After having a great time at the first two parks, they became frustrated at Grand Canyon when they could not travel further than the parking lot with Roth’s wheelchair.5 So, they decided to write a guidebook with accessibility concerns at the forefront. In 1992, they published Easy Access to National Parks: The Sierra Club Guide for People with Disabilities, Also Useful for Seniors and Families with Young Children. The book provided overviews of the access and barriers found at 50 national parks.

The authors gathered information by traveling across the United States in an adapted van. Roth’s multiple sclerosis affected her ability to walk and weakened her upper body. She used different types of wheelchairs and scooters, depending on the terrain and how her body felt. Both Roth and Tompane found much to love at the national parks. They wrote, “The parks became places to enjoy our common interests in exploration and we found a bond that transcends physical abilities.”6 But they also encountered different accessibility information at each park, making it hard to know what to plan for. Easy Access to National Parks sought to fill some of those knowledge gaps. The authors believed that better information would allow prospective visitors to make informed decisions for themselves.

Their research trips also showed the importance of thinking creatively about access. At Big Bend National Park, they rafted down the Rio Grande River by attaching Roth’s wheelchair to the raft. At Yosemite National Park, Roth took advantage of the sit-ski program at Badger Pass. Visitors with certain disabilities can ski down the slopes in a kayak-like device.7 The guidebook helped disabled visitors find valuable experiences at each park.

National Park Service. 2009

Roth and Tompane did not stop at sharing information. They also founded the Easy Access Park Challenge. Working within the National Park Foundation, a non-profit partner of the NPS, they connected volunteers with park staff to complete accessibility projects. The Easy Access Park Challenge improved access at 175 places in over 100 NPS sites.8 For example, they built an accessible trail to the Norris Geyser Basin and Echinus Geyser at Yellowstone National Park. Volunteers created the path by “clearing young and diseased trees, level the path, lay protection borders, provide water drainage…and where necessary, soil was compacted to allow wheelchair and stroller access.”9 Historically, many accessible trails were short and boring, excluding interesting features or views. This accessible trail avoided such pitfalls by bringing visitors with disabilities to one of the most sought-after thermal areas in the park.

Photo by Marissa Solini Photography

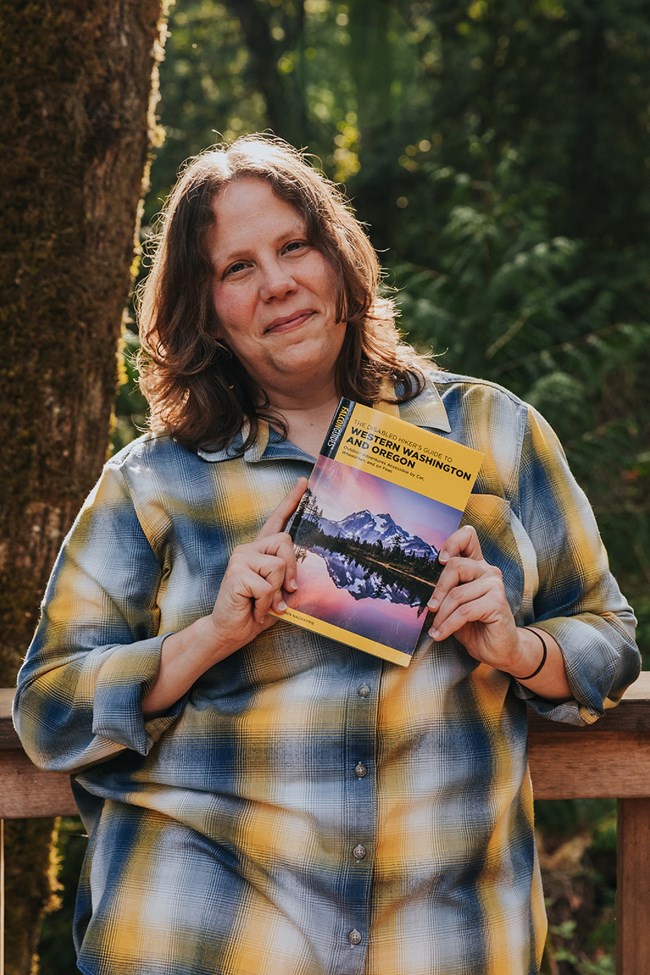

The Disabled Hiker’s Guide – 2022

In March 2018, Syren Nagakyrie decided to try out a new trail in Olympic National Park.10 Due to their chronic illnesses and disabilities, they were careful to research the hike ahead of time to know what to expect. All the guides called this particular trail easy. Yet, they encountered unexpected barriers immediately. There were “steep stairs and a narrow, scree-covered path along a steep drop off – with no guard rail.”11 They continued hiking until finally resting on a bridge overlooking a waterfall. They were tired and in pain, but also inspired. Nagakyrie went home that day and wrote a trail guide with the types of details hikers with disabilities would find most useful. Thus began Disabled Hikers, an organization that advocates for accessible outdoor recreation through trail guides, group hikes, and partnerships with parks.

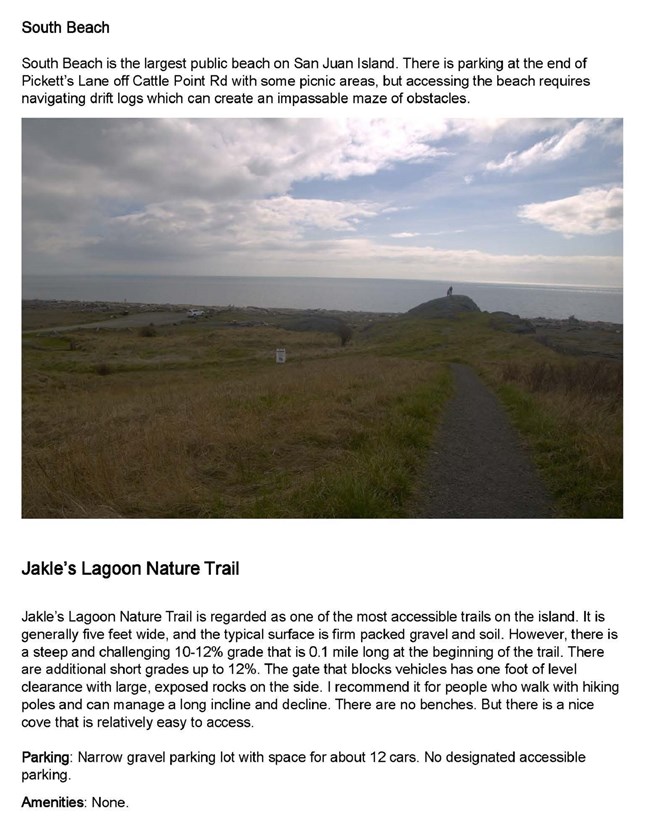

In 2022, Nagakyrie published The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon: Outdoor Adventures Accessible by Car, Wheelchair, and on Foot.12 They researched for more than a year, hiking over 150 trails to pick the 46 featured in the book. They looked for a wide range of trail lengths, elevation changes, and other attributes. “I really wanted to give a variety of trails,” Nagakyrie said, “because disability is so diverse and people have a variety of different access needs.” But all the featured trails needed to be easy to get to and provide “a meaningful experience” that would be “worth the trip.” The Disabled Hiker’s Guide expands what we consider accessible outdoor recreation. Though unusual in a hiking book, scenic drives and drivable viewpoints are included in the book. This is because Nagakyrie encourages all different types of outdoor experiences. They have often recounted their childhood memories of experiencing nature primarily in their yard or through a window. This guidebook reminds readers that there are many worthwhile ways to interact with nature.

Click on the image to read the Disabled Hiker's Guide to the San Juan Islands.

Nagakyrie’s guidebook champions the idea that specific, up-to-date information is central to accessible outdoor recreation. Instead of using typical easy-medium-hard descriptors for trails, they developed a unique rating system based on a trail’s length, grade, surface material, obstacles, and amenities.13 The high level of detail helps a hiker decide for themselves if a trail is right for them. This type of self-empowerment is particularly important to people with disabilities and chronic illnesses who, according to Nagakyrie, “are so often infantilized and not given the opportunity to really make their own decisions.”

Disabled Hikers continues to grow as accessible outdoor recreation remains as important as ever. The organization encourages people from around the US to share their stories on the website and is working on a leadership development program to train more disabled hikers to create guides. As the work expands geographically, they hope to trigger a larger culture shift to prioritize access throughout the outdoor recreation industry.

This article was written by Ellie Kaplan, MA, National Council for Preservation Education Intern, with the National Park Service Park History Program. 2023.

End Notes

1 Barbara Schaff, “Travel Guides,” Oxford Handbook of the History of Tourism and Travel, eds. Eric G.E. Zuelow and Kevin J. James (Oxford University Press, 2022).

2 The National Park Guide for the Handicapped (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1971), http://npshistory.com/publications/handicap-np-guide.pdf.

3 The National Park Guide for the Handicapped, 3.

4 “Center for Universal Design,” NC State University College of Design, https://design.ncsu.edu/research/center-for-universal-design/.

5 Mike Ervin, “Remembering the woman who opened the parks to people with disabilities,” The Progressive Magazine, March 27, 2001, https://progressive.org/op-eds/remembering-woman-opened-parks-people-disabilities/.

6 Wendy Roth and Michael Tompane, Easy Access to National Parks: The Sierra Club Guide for People with Disabilities, Also Useful for Seniors and Families with Young Children (San Francisco, CA: Sierra Club Books, 1992), 4.

7 Wendy Roth and Michael Tompane, “And Access For All,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 20, 1992.

8 Douglas Martin, “Wendy Carol Roth, 48, Author and Advocate for the Disabled,” New York Times, March 19, 2001.

9 Wendy Roth and Michael Tompane, “Norris Geyser Basin Accessibility Project at Yellowstone,” Courier 38 no. 6, Fall 1993, 3.

10 Unless otherwise noted, the information and quotes in this section come from an interview with Nagakyrie. Syren Nagakyrie, oral history interviews conducted by Ellie Kaplan, December 4 and 6, 2023. Harpers Ferry Center Archive, WV.

11 Syren Nagakyrie, “Disabled Hikers – Love Your Self, Love Your Place,” Washington’s National Park Fund, April 28, 2020, https://wnpf.org/2020/04/28/disabled-hikers-love-your-self-love-your-place/.

12 Syren Nagakyrie, The Disabled Hiker’s Guide to Western Washington and Oregon: Outdoor Adventures Accessible by Car, Wheelchair, and on Foot (Essex, CT: Falcon Guides, 2022).

13 Nagakyrie’s rating system is based on Christine Miserandino’s Spoon Theory from 2003. Miserandino uses spoons to represent finite units of energy. Collectively the spoons represent how much energy a person has to give to activities and tasks. A chronically ill person makes daily decisions about what they can do based on how many spoons of their limited supply a given task will cost them.