Last updated: December 14, 2023

Article

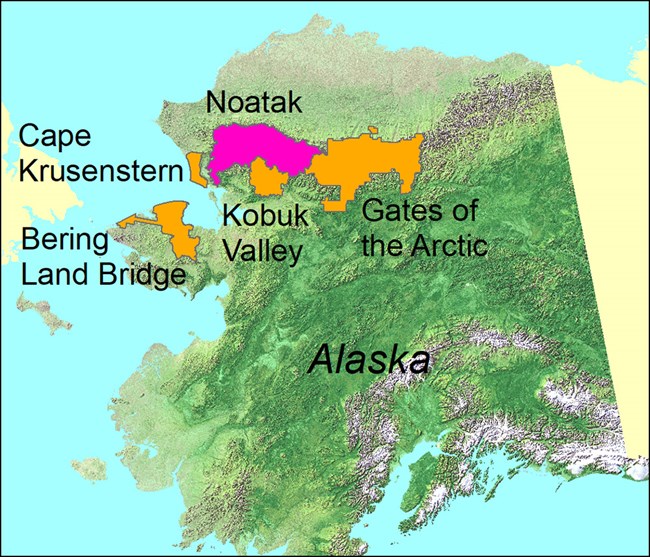

Old growth and new forests in the Noatak National Preserve

The Noatak National Preserve is mostly arctic tundra, but in a few places, there are forests of white spruce (Picea glauca) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera). The NPS Arctic Inventory and Monitoring Network (ARCN) monitors vegetation and landscape change in the five National Park Service units of northern Alaska. To understand tree growth at the cold limit of trees in northwestern North America, we collected tree cores and measured tree diameters and heights at 34 permanent monitoring plots. We examined tree growth rings in the cores and compared them to weather records and the dates of historic volcanic eruptions to understand tree growth rates as related to these environmental factors.

Key Findings

- The White spruce forests on mountain slopes in the study area are genuine old-growth forest as defined by the U.S. Forest Service. Trees more than 200 years old are common, and a few were more than 300 years old. We and other researchers have found these old-growth forests in the Agashashok, Kelly, and Kugururok River valleys, all tributaries of the Noatak River.

- Younger forests that became established in the 1900s are present near elevational tree-line in the mountains, in small patches of trees on rolling tussock tundra, and on river terraces and floodplains. The trees at tree-line and in tussock tundra are probably spreading in response to a warming climate, while the floodplain trees colonized newly exposed river bars.

- Tree ring widths show a lot of year-to-year variation, but had surprisingly weak responses to individual cold or warm years known from weather records, or the cold years that followed volcanic eruptions. The most marked volcanic effect was by the eruption of Tambora volcano (in Indonesia) in 1815, which appeared to reduce growth in most of the trees that were alive at that time.

- Most trees show a response in diameter growth to warm or cold temperatures integrated over the previous three to five years. This is probably the result of the cumulative effect of warmth or cold on soil and nutrient conditions, and on tree physiology.

- All the forests, old and new, showed continuing growth and addition of tree biomass between our initial visits in 2011 and return visits in 2021 or 2022.

How We Monitor Forests

We have nearly 500 permanent monitoring plots around the Arctic Network, and 93 of them have trees. We are in the process of revisiting these plots, and to date have new measurements from 45 of the plots in ARCN with trees, all roughly 10 years after the initial visit. We measure the diameters of all trees above 1.37 m (4.5 feet) tall, and count seedlings in four smaller subplots. We collect tree cores from selected trees just outside of the plots and measure the height of these trees. Back in the lab we count the annual rings in these cores and measure their widths, to understand changes in tree growth rates through time and how they may relate to environmental factors such as climate.

Management Implications

- The old-growth forests that grow in the hills of the Noatak Valley are a unique resource. These trees are generally small (less than 25 cm, or 10 inches) and distant from any habitations or travel routes, thus they are not likely to be in demand for subsistence timber harvest.

- Forests are expanding in the Noatak National Preserve. While the new forests are interesting and locally important, forest expansion is slow enough to be barely perceptible in a human lifespan and will not result in a major ecological change to the Preserve landscapes in the coming decades.