Last updated: January 9, 2023

Article

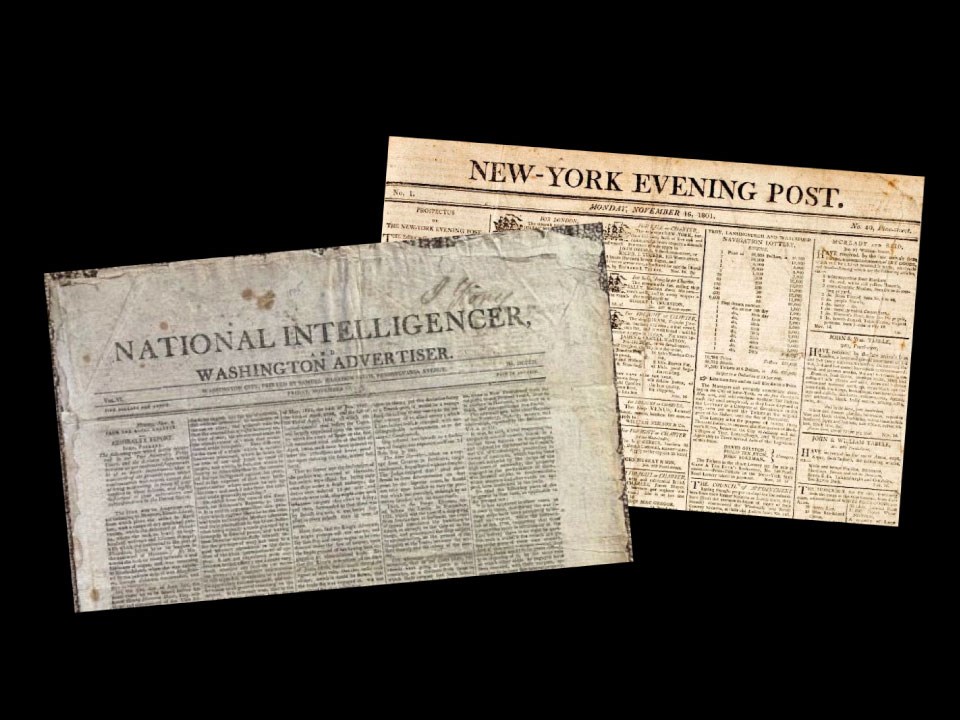

Newspapers in the time of Lewis and Clark

Public Domain.

In the early 1800s, newspapers bore very little resemblance to the business it is today. In a time long before radio, television, or the internet, papers were the primary source for regional, national, and even international news. But papers then usually had small circulations, were staffed by a limited number of people, and almost always were highly biased.

Most papers covered a single community or county and were typically “sideline” projects for printing houses. Few papers were considered “national” in scope.

At about 1790, the American press grew rapidly during the time when the First Party System began to develop – and both parties (Federalist and Democratic-Republican) sponsored papers to reach their loyal partisans and to strike out against their opponents.

Many historians point to the “Massachusetts Spy” as a key component to the American revolution – a paper that carried the patriotic message throughout New England and provided a template for other papers throughout the colonies.

By 1800, partisan papers were well established. In New England, Federalist-backed papers thrived; Pennsylvania was more balanced; and in the West and South, Democratic-Republican papers were dominant.

One Washington, D.C. paper that extended both north and south was “The National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser,” the first paper printed in the capital city and remembered for being the first to provide detailed reports of congressional proceedings. The paper was owned and managed by Samuel Harrison Smith, who was persuaded to launch the new paper in 1800 by Thomas Jefferson. As you’d guess, it became the official newspaper of the Democratic-Republican party, and Jefferson often referred to it as the only reliable source of information regarding government actions and positions.

Alexander Hamilton encouraged William Coleman to start the “New-York Evening Post” in 1801 to confront Smith’s paper and represent the Federalist viewpoints. While the “National Intelligencer” evolved several times, it ceased operations in 1870. But the “New-York Evening Post” continues to be published today as the “New York Post,” at slightly over 220 years old.