Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: Santa Fe Plaza

In September 1693, a group of hopeful soldiers and colonists—including priests, weavers, tailors, stonecutters, brick masons, carpenters, millers, ironworkers, shoemakers, a sculptor and two painters—departed Mexico City for a new life in the distant Spanish land of New Mexico. With wagons and livestock in tow, they trekked north along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro through the Chihuahua Desert to the southern reach of the Rocky Mountains. While some travelers deserted, and others died, 217 survived. When they finally arrived on the Santa Fe Plaza on June 24, 1694, they earned a place in history as the largest group then to have ever traversed the full length of El Camino Real.

They were not the first hardy travelers destined for El Camino Real’s northern terminus, nor would they be the last. Since 1610, when the plaza was founded as the social and economic center of the capital city of Santa Fe, a Spanish farming community established as early as 1605, trekkers, townspeople, traders, government officials and others had been lured by the trail’s promise of adventure and prosperity on New Spain’s northernmost frontier.

From the 1598 founding of New Mexico to the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, which forced Spaniards and their allies to flee Santa Fe on foot 400 miles south along El Camino Real to El Paso del Norte, triennial supply convoys kept settlers and missionary efforts alive. With the 1693 reclamation of the province by Spanish aristocrat Don Diego de Vargas, a mutually tolerant tone was struck between Pueblo peoples and returning Spanish residents. By the 18th and 19th centuries, the plaza’s cachet as a destination for culture and commerce, and the terminus of some of the most-trod trails in western history, was known throughout the Western world.

Today, Santa Fe stretches in every direction around the plaza, whose original form and surrounding building facades show centuries of change. Yet the site remains firmly fixed in the city’s storied history, drawing local and international visitors who wish to experience part of its Spanish and Mexican heart. The Palace of the Governors, the longtime seat of the Spanish, Mexican and U.S. governments in New Mexico, still flanks the plaza’s northern end. To the east, the Territorial-era Basilica Cathedral of St. Francis stands on the site of the city’s original adobe parróquia (parish church).

The plaza-based military presidio and chapel are long gone, and the open-air markets that characterized the plaza’s commercial heyday are largely lost to the modern business age. The plaza’s distinction as a historic conduit of international exchange, however, is unchanged.

The plaza was not the original endpoint of El Camino Real. That honor extended to the first provincial capital, located 30 miles north along the trail at a Tewa Indian site that founding Governor Juan de Oñate called San Gabriel. Oñate’s failure to establish a prosperous government there, as well as concerns that the Spaniards had illegally settled too close to Pueblo lands, prompted the Spanish Crown to appoint a new Governor, Pedro de Peralta. His first order of business was to move the capital south to Santa Fe.

Peralta laid out the new villa real (royal town) according to Spanish law, with a central plaza surrounded by the principal institutions of church and state—a palace, a presidio and a parish church. The rectangular packed-earth lot was designed to accommodate everything from political ceremonies and religious processions to commercial markets and “fiestas in which horses are used.” Though now the size of a square city block, the plaza was then twice as spacious. By the time of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, the town was surrounded by a large defensive wall.

Eventually, the wall gave way and, in addition to residences of military and government officials, the plaza area became home to the social elite. Many of them were among waves of colonists who followed El Camino Real to the plaza throughout the Spanish colonial period. By the mid-18th century, the plaza was also the end goal for privately contracted caravans that made annual trips between Mexico City and Santa Fe. Along with domestic and defensive goods, their stocks included silks, spices, glass beads, Chinese porcelains and other international luxury items that kept the far-flung villa connected with the world.

Still, Spain kept a tight rein on trade and travel in the province. Government officials monitored who came and went on El Camino Real and its growing network of roads and trails that accessed settlements from Taos to Albuquerque and beyond. A 1776 map of the plaza by Joseph de Urrutia features roadways radiating from the plaza to points south and north. The Camino del Alamo, for example, followed El Camino Real southwest along the Santa Fe River, past the parajes (rest stops) of El Alamo and Las Golondrinas, and south to Santo Domingo Pueblo, Socorro, the Jornada del Muerto and Mexico.

Only one merchant is listed in the Santa Fe census of 1790, though several local traders departed the plaza with loads of buckskins, piñon nuts and other homegrown goods. Mexico’s 1821 independence from Spain opened New Mexico’s borders to unrestricted international trade via El Camino Real and the new 800-mile Santa Fe Trail. Stretching from the plaza to Independence, Missouri, the trail connected New Mexico to markets throughout the U.S. Downtown Santa Fe was now the busy meeting point for purveyors from south, east and west.

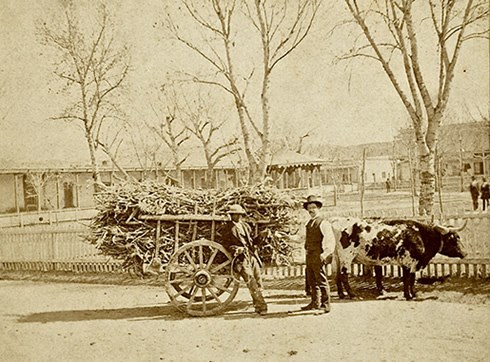

As caravans arrived in droves, and trail merchants erected temporary trade booths, the plaza became a hectic hub of loading, unloading, buying and selling. Some traders took a room at the inn on the plaza’s southeast corner or entertained themselves at surrounding gambling halls and saloons. Local and newly transplanted entrepreneurs, such as Captain Manuel Delgado of Santa Fe, took time off the trail to establish permanent storefronts on plaza-area streets.

In 1846, U.S. Army General Stephen Watts Kearny led troops along the Santa Fe Trail to claim Santa Fe as a military stakehold in the West. Like earlier Spanish and Mexican governments, Kearny maintained the plaza as a central post for his troops, part of whose mission was to protect traders along the Santa Fe Trail. As trade and travel increased, more Americans sought their fortunes in and around Santa Fe, whose reputation as a mysterious melting pot of cowboys, Indians, outlaws, soldiers, lawmen and residents with roots in the old and new worlds took on mythic proportions.

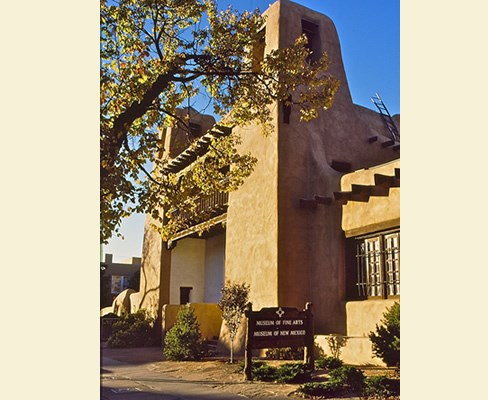

The Territorial period on the plaza saw fences erected, alfalfa planted and new American-style buildings constructed on three sides, effectively shrinking the square to its present size. In the 1880s, as the new railroad rendered El Camino Real and the Santa Fe Trail obsolete, the plaza became the focus of city leaders who deemed tourism to be Santa Fe’s ticket to the future. In 1909, the Palace of the Governors became a state history museum while various downtown buildings were built or remodeled in the new Spanish-Pueblo Revival style. Though historically contrived, the unique architectural style would ultimately identify Santa Fe worldwide.

With its flagstone walkways, warm-weather grasses and shady park benches, the modern-day plaza reflects little of the Spanish and Mexican character of centuries past. And questions of whether the site still serves the social interests of Santa Feans are the source of constant local debate. Nonetheless, the plaza remains at the core of the city’s cultural and civic identity, a go-to place for people-watching or attending a host of year-round community events. Anyone living in or visiting Santa Fe would be hard-pressed to ignore the plaza’s significance in the history and contemporary culture of New Mexico and the U.S. More than 400 years after the first travelers journeyed there along El Camino Real, the plaza’s legendary charms continue to draw people from around the globe.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.