Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: Palace of the Governors

The physical legacy of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro is imprinted across the New Mexico landscape in the form of trail tracks, wagon ruts and lengthy swales that appear and disappear in the dirt like wandering ghosts of time. The adobe Palace of the Governors has stood in solid witness to El Camino Real’s impact on the cultural, social and economic history of New Mexico and the United States since the spring of 1610. That year marks the date of construction of the Casas Reales (Royal Houses) as the seat of Spanish government in the newly designated capital city of Santa Fe, a Spanish farming community established as early as 1605.

With its long, shady portal bordering the north side of the city’s historic plaza, the Palace, now part of the state history museum, is a visual icon of modern-day Santa Fe. The sole survivor of the original Casas Reales, the earthen edifice has undergone various incarnations in structure and style since New Mexico Governor Pedro de Peralta received directions to erect a central block of buildings as the political hub of the provincial capital. As home for almost 400 years to Spanish, Mexican, American, and Pueblo Indian leaders alike, today’s Palace is the oldest continuously occupied public building in the U.S. An architectural anchor of the plaza, the Palace has also been a rare observer of, and an occasional participant in, the city’s commercial comings and goings.

In March 1609, the Spanish Crown ordered Peralta to move the capital to Santa Fe from San Gabriel, a site determined to encroach illegally on Pueblo lands. As all governmental functions moved south, the terminus of El Camino Real shifted to the plaza. For centuries to come, the adjacent Palace was a familiar sight at the end of the line for settlers and traders who hauled defensive, domestic and luxury goods from Mexico City to Santa Fe via El Camino Real.

During the province’s first 70 years, as settlers struggled to survive geographical isolation and tense relations with Pueblo neighbors, the Palace saw supply trains arrive only every few years. With the exception of items that colonists carried up El Camino Real, local access to cherished luxuries of European living depended on the vagaries of overland transportation. Thus in 1659, when the new Governor Bernardo López Mendizábal and his wife Doña Teresa Aguilera y Roche moved into the Palace, they brought a variety of specialty items—including European textiles, shoes, hats, sugar and chocolate. The clever couple set up a shop inside the Palace from which to sell the prized goods.

In August 1680, everything changed in the Palace and the province. Area pueblos rebelled, killing more than 400 Spaniards and 21 priests, and burning every torch-worthy trace of the Spanish occupation. More than a thousand colonists and their livestock fled to the Palace, where they withstood Indian assault until water supplies were cut off. After nine days in the Palace, Governor Antonio de Otermín and residents fled and walked 400 miles south down El Camino Real to El Paso del Norte.

By 1693, when Governor Don Diego de Vargas led soldiers and settlers back up El Camino Real to reclaim Santa Fe, the Palace had been transformed into a formidable, high-walled home of Pueblo peoples who moved in after the revolt. After a bloody battle, the Indians vacated, and the Spaniards resumed governmental control rebuilding the Palace and the province. Spanish-Pueblo relations eventually improved and travel and trade on El Camino Real picked up pace.

In 1821, Mexico won its independence from Spain and once-closed borders burst open for business. By 1822, Santa Fe was a bustling international port of entry for traders on the new 800-mile Santa Fe Trail that reached west from Missouri to the Santa Fe Plaza. There, the goods were bought, sold or moved on to Mexico along El Camino Real. As Chihuahua City developed into an important trail terminus in Mexico, El Camino Real between Santa Fe and Chihuahua became known as the Chihuahua Trail.

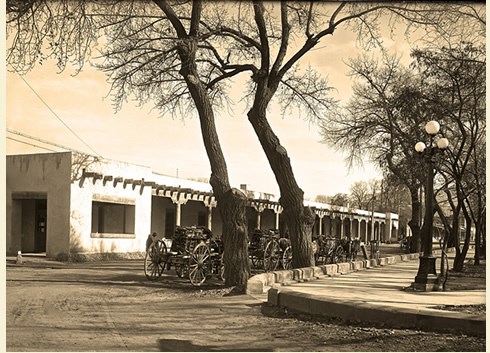

The Palace maintained a front-row seat on the action as partnerships between Mexico and the United States increased, and trade on the trails swelled to new levels of volume and profit. By the 1830s, more than half the commerce on the Santa Fe Trail extended into Mexico, while in Missouri the silver peso was a common means of exchange. Newly available window glass was installed in the Palace, where customs duties were now collected and traders rented rooms to store their goods. Local bakers, fruit vendors and other providers sold food to itinerant merchants on the Palace’s west side. By 1850, when New Mexico became a U.S. Territory, the majority of these private merchants and caravan owners were either New Mexicans or Mexican nationals.

In 1846, U.S. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny followed the Santa Fe Trail to the plaza and raised an American flag above the Mexican Palace. The Casas Reales had been reconstructed in the late 18th century into a massive blocks-long government complex with military barracks, with the Palace located in the far southeast corner. Much of the Palace was in a state of decay by Kearny’s arrival. Although not part of the original building, a portal of peeled logs and a dirt roof now spanned the Palace’s facade.

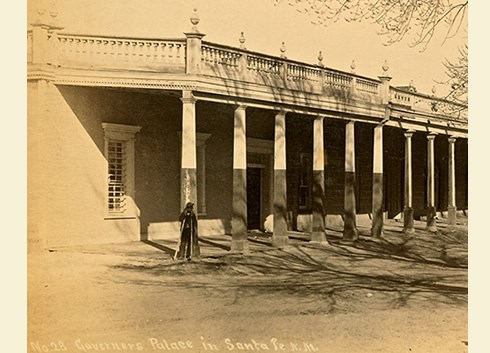

With Americanization came new U.S. imports along the Santa Fe Trail, including glass, brick and metal hardware and tools to establish lumber mills. In the following decades, many traditional Spanish-Pueblo buildings in Santa Fe were refitted with new architectural elements. The Palace portal received a drastic makeover in 1878, when it was replaced with a white Victorian-style “portico” with full-length balustrade. That portal survived until 1913, when an extensive restoration sought to return the Palace to its Spanish colonial roots.

By then, the railroad had revolutionized trade in New Mexico, leaving El Camino Real and the Santa Fe Trail winding into the past. In 1908, the construction of a new Governor’s Mansion brought to an end the Palace’s life as home to a colorful cast of 91 official, acting and interim governors. With the establishment of the Museum of New Mexico in 1909 as the caretaker of the state’s historical and cultural heritage, the Palace was reborn as a history museum. Since then, the Palace has served as both an artifact and an interpreter of the region’s rich history, including its years on the path of El Camino Real.

Today, the Palace is a National Historic Landmark and its period rooms and exhibitions are a main attraction of the New Mexico History Museum. The venerable Palace portal showcases works by American Indian artists from 41 pueblos and tribes who gather there daily to exhibit and sell their wares. Its Native vendors program and its participation in other annual marketplace events keep the Palace at the center of Santa Fe’s commercial and cultural exchange.

Palace of the Governors is a National Historic Landmark located on W. Palace Ave. on the plaza in downtown Santa Fe, NM. Click here for the National Historic Landmark file: text and photos. The Palace is home to the New Mexico History Museum. For more information, visit the New Mexico History Museum website. The Palace of the Governors has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.