Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: Mesquite Historic District

A vibrant pink adobe house makes a bold architectural statement on a back street of the Mesquite Historic District in eastside Las Cruces. The pink facade may not initially fit a visitor’s image of a centuries-old neighborhood at the cultural core of one of southern New Mexico’s oldest communities.

As a drive or walk through the district reveals, the area’s eclectic collection of homes and small businesses reflect the pioneering spirits of those who set down roots along the southerly path of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, then known as the Chihuahua Trail, after the Mexican-American War.

The original town site for modern-day Las Cruces, and a once-bustling section of El Camino Real, the Mesquite Historic District today stretches across Campo, San Pedro, Tornillo and Mesquite streets between Chestnut and Colorado avenues. From its block-long cemetery and grassy Klein Park to its whimsical gardens, mom-and-pop cafes and the home of the renowned Border Book Festival, the district is a colorful but unassuming counterpoint to the urban sprawl of greater Las Cruces, New Mexico’s second largest city. Its charming, homegrown hodgepodge of adobe architecture and vernacular styles offers a unique drive-by lesson on the social and cultural development of 19th- and 20th-century Las Cruces and southern New Mexico.

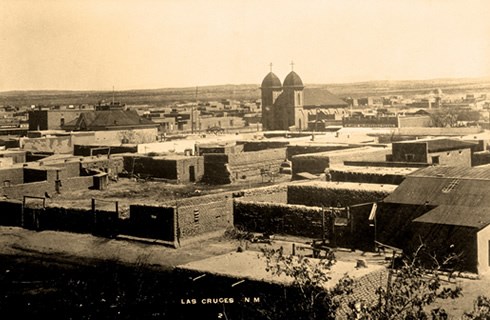

Las Cruces was established in the wake of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, when residents from the village of Doña Ana ventured six miles south along El Camino Real to settle a share of arable land in the central Mesilla Valley. As laid out by the U.S. Army in a plat signed by Doña Ana County Sheriff Samuel Bean, brother of the legendary Judge Roy Bean, the new town spanned approximately 76 blocks above the floodplain on the valley’s east side. The town was bordered on the west by the Acequia Madre irrigation ditch and on the east by El Camino Real.

The Army’s offer of free land drew a mix of Mexican-Americans, Pueblo Indian descendants, and Eastern-Americans to the tract overlooking the river valley where, prior to the Spanish incursion in New Mexico, the Manso Indians had lived. Although documents from the 17th and 18th centuries refer to the site as La Ranchería, a Camino Real paraje (rest stop), town leaders called the new community Las Cruces (The Crosses). Set at the edge of the Chihuahua Desert beneath the rugged Organ Mountains, the area was a frequent target of Apache raiders. The name is assumed to reference the cross-studded gravesites of settlers who died under Apache attack, though historical documentation is scarce. Some scholars point to an 1847 account by Susan Magoffin that noted a “solitary white cross” on the Chihuahua Trail as possible attribution. Others contend the name simply refers to the area as a crossing or crossroads.

One hundred and twelve settlers risked the danger to move to Las Cruces. After picking numbers from a hat to vie for the best home sites, they built a traditional, mostly adobe, community of small, low-slung houses with simple floor plans, and flat or low gable roofs. The earliest homes were in a cluster close together, their facades forming walls of protection along the street edge with courtyards stretching to the rear. The 1851 creation of nearby Fort Fillmore led to less defense-oriented structures that reflected the growing Anglo influences in the region as American settlers and trade items moved in greater numbers along El Camino Real. Taller gables and a wide variety of parapets, as well as Territorial brick coping, pedimented lintels, chamfered columns and spindle friezes brought vitality and variety to the town site’s traditional architecture.

Las Cruces developed slowly, supported mainly by trading, freighting, farming and some mining in the Organ Mountains. As Chihuahua Trail traders, American freighters and others took up residence, the town site expanded to the east and north. In addition to general stores and rooming houses, bars and brothels became part of the mix. Las Cruces became a playground for area cowboys, miners and soldiers from Fort Fillmore and Fort Selden, earning a reputation as a rowdy and dangerous town.

Despite its prime El Camino Real location, Las Cruces gained only modest growth and commercial success compared to neighboring El Paso and La Mesilla. With the arrival of the railroad in the 1880s, city leaders donated land on the town’s west end for a train depot and track. The railway brought new market opportunities to Las Cruces, but it effectively killed El Camino Real. It also fueled a building boom that further developed the town site’s architectural flavor, with highly adorned adobe and brick buildings and residences embellishing the turn-of-the-century streetscape. The growth and modification of established homes had an impact on the area’s traditional ambience, but the changes reflected the personality and originality of residents who, rather than moving elsewhere, invested further in their neighborhood.

Today, as home to some 713 historic homes and buildings, the district is only half its original size. In the 1960s, the razing of the entire western part of the district to make room for parking lots and non-traditional architecture was the result of a shortsighted urban renewal project. Other community projects have further altered aspects of the district’s original traditional character. Many of the changes contributed to the economic stagnation of the city’s old downtown. But recent efforts to boost awareness of El Camino Real and its history in the old neighborhood are heightening local pride in the trail, fueling architectural preservation initiatives and drawing new residents to the area’s traditional treasures.

Even as Las Cruces continues to change and grow around it and homeowners paint their houses pink, green, yellow, or blue, the old town site retains its historic heart. Many of the district’s oldest streets and buildings remain. Among them is the north-south Mesquite Street, which generally follows the original path of El Camino Real. Weaving through the district’s narrow streets to view its funky and fantastic sights is a reminder to visitors that, like our own lives, El Camino Real crosses through the spectacular and the mundane to connect history to today.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.