Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: Mesilla Plaza and Mesilla Historic District

In 1849, Valentin Maese erected a two-room home for his family just east of what would become the formal plaza in the small Mexican village of Mesilla. Maese’s vertical log and adobe plaster jacal was simple and practical, joining other jacales built along the plaza perimeter as a means of community defense. Established on Mexico’s northern frontier in 1848, west of the Rio Grande and El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, Mesilla was an easy target for Apache Indian attacks. Even so, Maese and Mesilla’s other proud pioneering families would rather risk raids than lose their cultural identities as Mexicans after the 1846 Mexican-American War left their former homelands in U.S. hands.

The U.S.-Mexico boundaries established by the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo encompassed the verdant Mesilla Valley, a broad sweep of agricultural terrain that stretched north to Doña Ana, New Mexico, where many of Mesilla’s founders had previously lived. Though the Mexican government believed the settlers’ crossing of the Rio Grande southwest into the valley situated Mesilla in Mexico, the U.S. government disagreed. Mesilla lingered in a virtual no-man’s land through years of political wrangling until the 1854 Gadsden Purchase officially made it part of the U.S. Territory. When the American flag was finally raised over Mesilla Plaza, the town was already well on its way to greatness as a hub of culture, transportation and trade on El Camino Real.

Today, sitting in the posh Double Eagle Restaurant—one of the oldest plaza buildings and the site of Maese’s two-room house—Mesilla’s evolution from a gritty, rebellious frontier town to one of New Mexico’s grandest historical communities unfolds. With its spacious rectangular plan and central courtyard, the Territorial-style Double Eagle is an architectural metaphor for Mesilla’s upbringing. In addition to Maese, some of Mesilla’s earliest residents occupied the space, including the Guerra, Valencia and Gamboa families.

While Mesilla’s 2,000-plus residents might easily be overshadowed by Las Cruces, New Mexico’s second largest city two miles to the northeast, their preservation of the town’s cultural identity and architectural history makes Mesilla a don’t-miss destination. Whether wandering through the plaza and commercial core, or following the acequias (irrigation ditches) that border the historic district and feed local farmlands, Mesilla is a small walking town with big stories at every turn. Buildings that best represent Mesilla’s period of historic significance reflect the town’s growth and influence in the region between 1849 and 1885, and many have changed only slightly since the town’s founding. Tales of the town’s intriguing inhabitants, past and present, are perfect companions for an engaging educational visitor’s experience of the 19th-century heyday of Mesilla and El Camino Real.

As in most traditional New Mexican Hispano communities, Mesilla’s plaza is the cultural and geographical axis around which the town narrative revolves. A simple church was constructed on the plaza’s south side with the village’s establishment. By 1857, it had been replaced by a traditional adobe church at the plaza’s north end. That church was replaced in 1906 by today’s San Albino church, a yellow-brick building whose facade is dominated by square belfries with pyramid towers and soaring, arched stain-glass windows. As the plaza’s primary architectural anchor, San Albino continues to reflect the prominent role of religion in the community’s history. In 2008, the church’s historical importance was recognized as it was designated as one of two basilicas in New Mexico.

From its origins as a simple dirt lot, the plaza has developed through time with paving, landscaping and a replica 1930s-era bandstand, creating a more modern, but no less inviting, social center. The pristine commercial and residential buildings that border the plaza reflect Mesilla’s maturing as a prime location on El Camino Real and on the southern route to California, where gold was discovered in 1849. The 1851 establishment of nearby Fort Fillmore and protection by its soldiers allowed for development of a less defense-minded community with a traditional architectural character. One-story, flat-roofed adobe homes replaced log jacales around the plaza and in the outlying historic district, where vast acequia networks provided plentiful water for farming.

Mesilla’s transition to a U.S. Territory quickly bolstered trade in all directions along the Santa Fe Trail and El Camino Real, then known as the Chihuahua Trail. Mesilla became a vital military supply center, providing merchandise for area forts as well as for Confederate troops, who occupied Mesilla in 1861-62. By then, businessmen, merchants, freighters and others had populated the plaza with shops, hotels, restaurants, bars and other amenities.

Between 1860 and 1863, Mesilla merchant Augustin Maurin, a French émigré, used hand-fired brick from a local kiln to construct the Leonart-Maurin Store on the plaza’s southwest corner. Maurin’s murder in his next-door apartment halted construction, including a planned second-story addition. Nonetheless, hand-hewn vigas (ceiling beams) and other architectural details have been retained through the building’s various incarnations as a saloon, a residence, a town hall and more. Today, Maurin’s creation endures as one of the earliest local-brick buildings in New Mexico.

Other enterprises operated out of impressive adobe and brick buildings that frequently included a residence for merchant owners at the rear of the property. Among these merchants were Anastacio, Rafaela and Mariano Barela, a family of prominent native New Mexican traders who established an adobe general store on the plaza’s west side in the1850s.

A zaguan (meaning a covered passageway) led to the rear of their home. In 1870, new merchant neighbors, J. Edgar Griggs and Charles Reynolds, moved in next door to the Barelas and established a spacious new mercantile that became one of southern New Mexico’s finest.

The Reynolds-Griggs store occupied two adjoining buildings, with the feed and grocery departments housed in the southernmost portion and a dry goods and notions department on the north. A zaguan separated the spaces and led to the patio of the Griggs residence at the shop’s rear. When Griggs died in 1877, Reynolds continued to operate the business, eventually passing it down to his son, Charles. In 1903, Charles purchased the Barela store and home, which eventually featured a Territorial-style facade with a triangular parapet and pedimented windows and doors.

Today, the Barela and Reynolds buildings comprise the historic residence of J. Paul Taylor, an influential former New Mexico legislator who, with his late wife Mary, purchased the properties in 1953. The Taylors further expanded the rambling adobe residence to house their large family and a major collection of historic New Mexican art and furnishings. Their history-minded efforts have preserved the Taylor-Barela-Reynolds building as one of the most historically significant structures in Mesilla. While the elder Taylor still lives there, the Taylor family in 2003 donated their home and adjoining properties to the State of New Mexico to be opened to the public eventually as an historic site.

Charles Reynolds’s rebuilding of the original Griggs-Reynolds store, the southernmost portion of the Taylor property, illustrates the major impact of Mesilla’s prime position as a Southwest transportation hub with access to a far-reaching range of building materials and other resources. Reynolds rebuilt the store’s adobe facade, adorning it with pressed metal, plate-glass windows and a bracketed metal cornice. Juxtaposed against the classic Territorial-style Taylor residence, the building symbolizes the continued architectural development of Mesilla as a town that balanced proud traditional values with economic progress.

With more than 2,500 residents by the close of the 1860s, Mesilla was the biggest city between San Antonio and San Diego. By the 1870s, it was the county seat and the Mesilla Valley’s leading center of trade. In addition to El Camino Real, the town’s trade connections were maintained through a variety of stage, freight and mail routes, including the Butterfield Overland Mail, San Antonio Mail and Wells Fargo Express. At various times, these operations were based in the town’s “transportation block” at the plaza’s south end. The one-story building also comprised a varied collection of commercial establishments, including a corner bar that remains one of Mesilla’s major destinations.

Local land commissioner Guadalupe Miranda opened the first saloon on the site in the 1850s. The bar later became the property of Sam Bean Sr., who ran the business with his son, Sam Bean Jr. Anyone looking out on the plaza from a bar stool at the Beans’ saloon on August 27, 1871, would have witnessed a political parade that inspired one of the bloodiest incidents in New Mexican Territorial history. After drinking their share of campaign whiskey, rival Democratic and Republican parade participants rioted. Troops from nearby Fort Selden were called in to restore order, but by the time it was over, nine men were dead and 50 wounded.

Today, the gunsmoke has cleared, but the corner bar remains. Operating on the site since 1936, El Patio Bar continues the tradition of offering libations to Mesilla residents and visitors. Anyone looking for an authentic taste and feel of Old Mesilla would be wise to duck into El Patio, pull up a bar stool close to the door and watch the plaza passersby.

The transportation block also hosted a series of newspapers, including the Mesilla News and Confederate Mesilla Times. Among Mesilla’s most prominent newsmen was Colonel Albert Jennings Fountain, an attorney and probate judge who first came to Mesilla in 1862 with Union forces and married Mariana Perez, a member of a prominent Mesilla family. Fountain’s son, Albert Fountain Jr., and many town leaders, including merchants Albino Frietze, Griggs and Reynolds, and the Reverend Augustine Marin, lived in the so-called “California District,” northwest of the plaza. Their spacious properties and fine, large Territorial-style homes symbolized the rising affluence and wealth of some of the 19th-century Mesilla residents.

The Fountain family loved theater, and in 1874, Colonel Jennings and Albert Jr. renovated a building on the plaza’s northwest corner as the Mesilla Valley Opera House. In 1905, Albert Fountain Jr. built a new theatre on property that in 1861 had served as the Confederate headquarters of the Territory of Arizona. There he established the Fountain Theatre as a showcase for plays, vaudeville, light opera and silent films. The Fountain Theatre survived the advent of talking films and high technology and today is the oldest documented theatre in New Mexico still in operation.

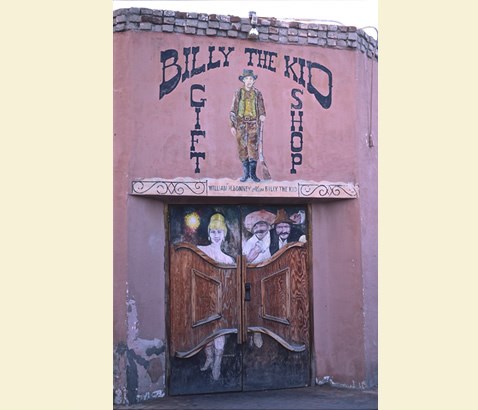

With its theaters, shops, saloons and local color, Mesilla drew visitors from throughout the Southwest and Mexico looking for a good time. Billy the Kid was a frequent Mesilla visitor who spent time as an inmate at the Territorial-style adobe jail and courthouse on the plaza’s southeast corner. More well-mannered visitors stayed across the street at the Corn Exchange Hotel, a rambling, single-story adobe compound with brick coping and parapets and an interior courtyard. Constructed as early as 1854, the building was an important stop on the Butterfield stage line before the hotel opened in 1874. Since 1939, the 10,000-square-foot building has been home to La Posta Restaurant, a popular spot for native New Mexican cuisine operated by descendants of the Griggs mercantile family.

The railroad bypassed Mesilla for Las Cruces in 1881. As El Camino Real and other trade connections became outmoded, Las Cruces became the new commercial and cultural darling of southern New Mexico. Rather than being derailed by progress, Mesilla’s preservation of its historic acequias and farming traditions allowed it to recede quietly, and proudly, back to its agricultural roots. The town’s thoughtful development during the 20th century, and residents’ care for their historic architecture, preserved Mesilla’s modest scale and authentic small-town feel. Today, the plaza and most of the buildings facing the plaza are listed as a National Historic Landmark. Likewise, the acequias and blocks of traditional residential buildings that radiate beyond the plaza into the greater historic district also are listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Unlike many Camino Real communities that have withered through time, Mesilla remains a vital voice and vision of the Mesilla Valley’s unique political, cultural, commercial and social past. While most plaza buildings are dedicated to tourist activities, historic preservation regulations ensure that they and other structures in the historic district continue to speak to Mesilla’s distinctive architectural history. Equally important is the town’s ongoing observance of cultural traditions and customs. They flow through daily life on the plaza and in the historic district, from the acequias through the pecan groves, to the barns, businesses and homes where local families, many of them descendants of the original founders, continue to work and live.

Walking past the old blacksmith’s shop of Simon Guerra, the town judge who as late as the 1960s held court in his fiery forge, a visitor can almost hear the sounds of Guerra’s hammer, or gavel, striking his massive anvil. Guerra, like other proud Mesilleros of yesterday and today, chose not to trade the past for the present. Instead, they—like visitors to Mesilla today—discovered contentment in the company of both.

Mesilla Plaza is a National Historic Landmarks located in Mesilla, NM, approximately four miles south of Las Cruces on NM Route 28. The Mesilla Plaza is in the center of town, bounded by Calle de Principal, Calle de Parian, Calle de Guadalupe, and Calle de Santiago. Click here for the Mesilla Plaza’s National Historic Landmark file: text and photos. Mesilla’s J. Paul Taylor Visitor Center is located at 2231 Avenida de Mesilla, inside the Mesilla Town Hall. For more information, visit the Town of Mesilla website or call the visitor center at 575-524-3262 extension 117.

Mesilla Plaza, the Iglesia de San Albino and the Barela-Reyonds House have been documented by the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

Photo © Jack Parsons