Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: La Bajada Mesa

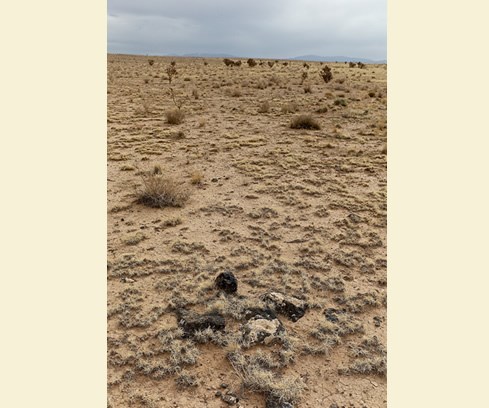

A frigid wind powers across the juniper-studded grassland plain of La Bajada Mesa, fiercely determined to make its final destination. The travelers who braved wind and other weather to climb and cross the formidable mesa between the 17th and 19th centuries were equally determined. They chose the most difficult route of El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro to enter or depart the New Mexico capital of Santa Fe.

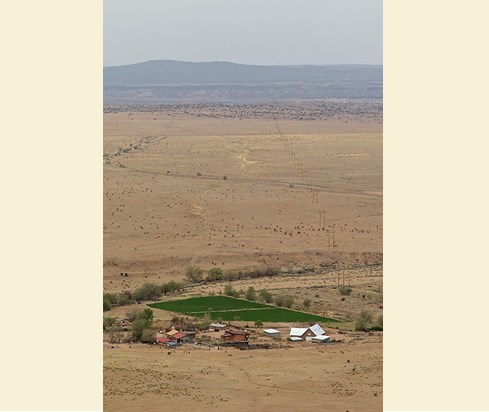

Because of its remote and rugged locale, La Bajada Mesa is among the best preserved and historically significant sections of El Camino Real today, with well-worn tracks, swales and other reminders of travelers past etched permanently into the landscape. Only the best prepared, and most adventurous, modern-day trekkers will want to take on the black basalt backcountry of La Bajada. The beauty of the view from the mesa top, however, is well worth the effort. Gently sloping approximately six miles northeast to southwest, La Bajada Mesa intersects with Interstate 25 about 10 miles southwest of Santa Fe. The vast open space reveals precontact stone piles from early agricultural grids that demonstrate how native cultures creatively engineered the area’s natural resources to raise successful crops. Archeological evidence points to new tools and resources introduced after European contact.

By far, the mesa’s most defining feature is at its southwest edge, where the volcanic escarpment upon which the mesa sits towers 600 feet high over the plains below. Appropriately known as La Bajada (The Descent), the overlook is one of New Mexico’s most spectacular natural landmarks. It provides an awesome perspective on the great lengths—and heights—that El Camino Real travelers trod on their epic journey.

Beyond its importance as a geological landmark, La Bajada escarpment is a major cultural landmark. The routes built to cross La Bajada between 1598 and 1932 follow precontact pathways across the mesa, indicating its importance to native cultures who utilized natural topography, grade changes and drainage systems to best utilize the mesa top. Following the arrival of Spaniards in the region, La Bajada stood as the dividing line between New Mexico’s primary economic and governmental districts: the Río Abajo (lower river) and the Río Arriba (upper river).

For those traveling the north-south El Camino Real between the districts, there were three clear routes: one gave travelers the choice of scaling the basalt behemoth, another followed the Santa Fe River through the yawning canyon of Las Bocas (the Mouths), and the third required another, longer trek around La Bajada through the Galisteo Basin. Initially, the La Bajada option was limited solely to pedestrians or livestock. Despite legends to the contrary, the heavy supply wagons and commercial caravans that traveled El Camino Real could not take the La Bajada route until the 1860s, when the U.S. Army made improvements that allowed for wagon passage.

Archeological evidence indicates that, despite its challenges, the La Bajada route was an attractive option. A water hole in a canyon directly adjacent to El Camino Real highlights a system of handmade dams that formed a deep plunge pool. A trail leading from El Camino Real to and from the pool indicates continuous human and livestock traffic. By the early 1700s, Spanish settlers had established the small village of La Bajada at the base of the escarpment. The settlement sat beside the Santa Fe River, close to an abandoned pueblo village that was still occupied when Don Juan de Oñate led the first colonizing expedition to northern New Mexico in 1598.

Diverse voices have referred to La Bajada, the place and the landmark, throughout history. In 1776, a Franciscan priest, Fray Atanasio Domínguez, described La Bajada Mesa as “a mesa [that] rises….flattening out on top…to a very steep slope….” In 1807, explorer Zebulon Pike mentioned both the village and the escarpment as he detailed his journey across La Bajada Mesa on his way to Mexico, writing, “We ascended a hill and galloped on until about ten o’clock, snowing hard all the time, when we came to a precipice which we descended, meeting with great difficulty, from the obscurity of the night to the small village where we put up in the quarters of the priest….”

Chroniclers of the early Territorial period made less frequent reference to the El Camino Real-La Bajada route as traffic through Las Bocas and the Galisteo Basin became more common. With Mexico’s victory over Spanish lands in 1821, and the strengthening of trade connections between Mexico and the U.S. via the Santa Fe Trail and El Camino Real-Chihuahua Trail, the La Bajada route regained traction as the most direct path to and from Santa Fe. Little La Bajada village, whose population peaked at 300, emerged as another important trading center, freight depot, stage stop and rest stop for El Camino Real travelers heading north and south. With the American occupation of New Mexico in 1846, the U.S. Army took note of the route’s potential, finally improving the roadway for heavy wagon use.

Even with the improvements, La Bajada remained a grueling excursion. In 1869, U.S. Army Lieutenant John Bourke described the descent as “…so risky that stage passengers always alighted and made their way on foot, while the driver found abundant occupation in taking care of his train and slowly creeping down with a heavy brake on the wheels locked and shod and the conductors at the head of the leaders….”

Three years later, John Handson Beadle recalled his trip south across the mesa to the escarpment on a freight wagon, writing, “Crossing the high mesa, level as the sea, we approach an irregular line of rocks, rising like turrets ten or twenty feet above the plain, which we find to be a sort of natural battlement along the edge of the big hill. Reaching the cliff we see, at an angle of forty-five degrees below us, in a narrow valley, the town of La Bajada. Down the face of this frightful hill the road winds in a series of zigzags, bounded in the worst places by rocky walls, descending fifteen hundred feet in three-quarters of a mile.”

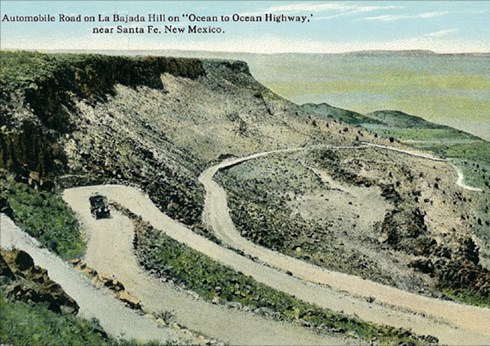

El Camino Real was abandoned as a major commercial corridor with the 1881 arrival of the railroad, but La Bajada Mesa’s importance as a transportation corridor continued. Not long after the wagons stopped running there, Model A automobiles began lumbering along the path. Between 1903 and 1926, a segment of the mesa trail as it approaches the escarpment edge became New Mexico Highway 1, part of the National Old Trails Road Highway system. During the 1915-1916 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego celebrating the opening of the Panama Canal, scores of vehicles a day are estimated to have traversed the mesa path on the way to California. Between 1926 and 1932, the same area became the avenue of the fabled Route 66. Adventurous tourists of the period traveled the roads with the famous Harvey House Indian Detours while on their way to explore area pueblos and other cultural sites. By the time the route was abandoned and moved a few miles to the east where the interstate is located, an estimated 1,200 vehicles were traversing La Bajada Mesa a day.

Experiencing El Camino Real today across La Bajada Mesa is a stimulating test of nature and one’s spirit of adventure. The rutted mesa road, which moves through Bureau of Land Management and U.S. Forest Service lands, requires a high-clearance SUV and adequate provisions for hiking or emergencies. For a close-up view of the various El Camino Real tracks taken and abandoned through time, the best, and most authentic, option for exploring the mesa is on foot. Parallel roadways mark where caravans and livestock traveled side by side, while in other areas, stones form low curbs along the roadside. Moving toward the escarpment edge, the ground gets rockier and the sky gets bigger until the landscape unfolds in dramatic fashion as far as the eye can see.

Peering off the edge of the cliff, one directly overlooks the harrowing switchback road with 23 hairpin turns that carried late 19th-century wagons and early 20th-century motorists up and down La Bajada. The road remains protected by retaining walls built by laborers from the state penitentiary and nearby pueblos.

At the foot of the escarpment is the picturesque village of La Bajada, now home to but a few residents. Like an old-fashioned picture lost in time, the village still sits in isolation, as if oblivious to the shifting winds of history that move through and around it. Looking further south, to the plains beyond the village, squiggly patterns of El Camino Real pathways appear and disappear in the dust, perhaps still uncertain of the best way to conquer La Bajada.

La Bajada Mesa is located 18 miles southwest of Sante Fe, NM (Latitude: 35.5689221, Longitude:-106.2003011). Do not attempt to drive down the slope for the road is very rough and Pueblo of Cochiti land is half way down the slope. Permission is needed from the pueblo for any access to its lands in this area.

While a La Bajada Mesa outing is a rare and exciting experience, travelers should be prepared and cautious. High-clearance vehicles are the best and safest option for travel, though a trip to the mesa during or following rainfall is never wise. Bring plenty of water and other emergency resources, including a first aid kit. Rattlesnakes can be a risk factor. Surveying the landscape by car or on foot via the dirt road, some of which is laid on top of the old Camino Real, is advised. Vehicles are not allowed off the existing dirt road.

Driving Directions: La Bajada Mesa is located as the crow flies approximately 18 miles from downtown Santa Fe, NM. From the intersection of Cerrillos Road and Paseo de Peralta in downtown Santa Fe, proceed five 5 miles southwest on Cerrillos to Airport Road and turn right. Take Airport Road toward the Santa Fe Airport about 3.1 miles to where it turns into County Road 56. Continue 3.3 miles on County Road 56 to County Road 56C and take a hard right turn, heading up the slope to the west. Stay on County Road 56C, which will loop around to the left and turn into Forest Road 24. Proceed on Forest Road 24 for about 7 miles to the edge of the escarpment, on Santa Fe National Forest land. You will also cross private and Bureau of Land Management lands. Do not attempt to drive down the escarpment since the road is very rough and since the Pueblo of Cochiti land is half way down the slope. Permission is needed from the pueblo for any access to its lands in this area.

La Bajada Mesa has been documented by the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.