Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

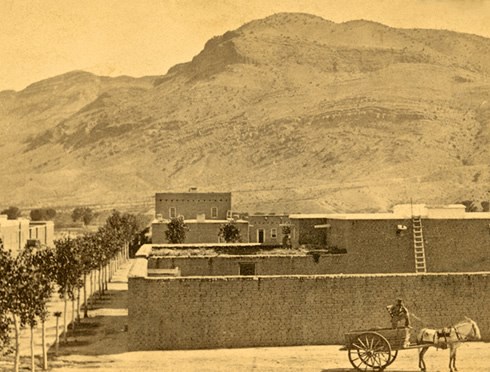

New Mexico: Fort Selden Historic Site

Courtesy Palace of the Governors Photo Archives (NMHM/DCA. Neg. #001705)

An account from Lieutenant James Henry, Fort Selden, New Mexico, October 3, 1866:

“Dearest Annie: The Commanding Officer is going on a sixty days scout in a few days. I expect to go with the party. We will travel west by north and pass through a country of which little is known. Trappers report that there is any quantity of Gold on a river, supposed to be the Sacramento.

Miners that went there, never returned, but we calculate to go there with one hundred men, punish the Indians, and return (some of us)….Buenos Noches, mi Caro Annie, Yours, Harry.”

So wrote Lieutenant James Henry “Harry” Storey to his sweetheart, Miss Annie Cheshire of Brooklyn, New York, shortly after his arrival at Fort Selden. Built 18 miles north of Las Cruces on the east banks of the Rio Grande amid the remnants of a precontact Mogollon village, the frontier Army post was established a year earlier in 1865 to protect travelers, traders and others who ventured through New Mexico’s remote Mesilla Valley along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

Storey was among the first of many U.S. Infantry and Calvary troops to occupy the fort, including the legendary African American Buffalo Soldiers of the 125th Infantry. The large adobe garrison was a foreign and lonely place for a New Yorker like Storey and others sent to defend travelers in the tough southwestern terrain from marauding Mescalero and Mimbres Apaches.

Today, Fort Selden stands as a ghost of itself and their memories in the shadow of the soft-curving Robledo Mountains, whose name honors the fate of Pedro Robledo, a member of the 1598 Juan de Oñate expedition and the first European to die on El Camino Real in what is now the United States. The fort’s random collection of crumbling adobe walls and earthen mounds suggests a once-extensive series of 15 to 20 buildings laid out, in traditional military fashion, in a rectangle around a central parade ground. While some stone foundations still support walls stretching up to 10 feet high and a few cottonwoods tower overhead in full leaf, most of the fort is eroding back into the landscape it was built to protect.

Nonetheless, the stories Fort Selden holds and its historic significance as a late-19th century Army fort continue to fascinate visitors who wish to connect to El Camino Real, U.S. military history and the West’s captivating frontier past. Designated as a New Mexico State Monument in 1974, Fort Selden is now under the umbrella of the Museum of New Mexico, which preserves it as a state historic site with an onsite visitor center featuring exhibitions and living history demonstrations on frontier and military life.

Now quiet and indistinct on the outside, Fort Selden was once a bustling, tree-laden community on the inside, where some 200 men lived and worked. Enlisted men’s barracks stood at the south end of the parade ground facing officers’ quarters to the north. To the east was the fort’s sole two-story building, housing administrative offices, workshops, a courtroom and a stone prison. The west side was the site of a 10-bed hospital with a resident surgeon. Kitchens, storerooms, corrals and a trader’s store rounded out the world of Fort Selden.

While the commanding officer lived in a comfortable six-room house with his family and their servants, the enlisted men’s experience was not quite so hospitable. Their days were largely a monotonous routine of exhausting drills and hard labor fueled by a meager diet of bread, meat and beans. They spent their nights in bug-and-rodent-infested quarters with poor ventilation. Worse yet, it was boring, leading soldiers who did not desert to entertain themselves with booze, gambling and frequent violence. As Lieutenant Storey wrote to his beloved Annie, “You have no idea, my dear child, what a life we lead. It is a continual round of dissipation.”

Indeed, despite the soldierly romance of battling Indians, Fort Selden troops saw more action in shootouts and knifings in nearby Leasburg, or at the fort itself, than in combat with Indians. What with escorting civilians through the desert, periodic scouting patrols and occasional calls to assist civil authorities in keeping order in rowdy frontier towns, Indian fights were few. Only three soldiers died in combat with Indians during the fort’s 25-year life.

Before construction of the fort, El Camino Real ran high along an alluvial terrace above the floodplain. A new branch of the trail later dropped to the west to cross through the fort. By the mid-1870s, however, Indian conflicts had so dramatically waned that the U.S. War Department initiated action to abandon the fort.

It was nearly deserted four years later, though not for long. In 1880, the War Department reactivated Fort Selden as it turned its attention to territorial expansion via the burgeoning railroad, which quickly rendered El Camino Real obsolete.

Under the leadership of Fort Selden’s new commander, Captain Arthur MacArthur, soldiers now ensured the safety of railroad employees installing new rail lines parallel to the Rio Grande. MacArthur undertook an extensive restoration of the fort, which was already crumbling under years of weather and wear. Among other things, he improved the enlisted men’s quarters and installed billiard tables to keep them positively entertained. From 1883 to 1886, MacArthur lived at the fort with his wife Mary and sons Arthur III and Douglas, who would become a legendary Army general in World War II. Long before then, young Douglas MacArthur learned to shoot a rifle and ride a horse at Fort Selden.

The improvements to Fort Selden put it in the running to become a permanent regional installation serving southern New Mexico, but Fort Bliss in Texas ultimately earned the distinction. The last troops left the fort in 1891. In the early 1970s, as the fort began a new chapter as a historic site, new efforts to preserve and restore the property got under way. Native grasses and a ring of cottonwood trees were planted as soldiers would have seen them in the fort’s heyday. Though only a few trees survive, their spare calligraphic forms now frame the old rectangular parade ground and accentuate the drama of the days that Lieutenant James Henry Storey and other soldiers spent there.

As Storey wrote his dear Annie two months before his final discharge and return to her in New York, “…Such is a soldier’s life. Today all is life and gaiety. Tomorrow we embrace mother earth.”

Fort Selden Historic Site is located in Radium Springs, New Mexico (13 miles north of Las Cruces, NM). For more information, visit the New Mexico Historic Sites website.

Fort Selden has been documented by the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.

Photo © Jack Parsons