Last updated: July 2, 2020

Article

New Mexico: Fort Marcy Ruins

On August 19, 1846, three months into the Mexican-American War, U.S. Army Lieutenants William H. Emory and Jeremy F. Gilmer scaled an 80-foot bluff to survey the scene above the newly occupied Mexican city of Santa Fe. It was located approximately some 600 yards northeast of the historic plaza and Palace of the Governors. The hilltop would be the foundation for an adobe fort designed by Gilmer as the Army’s defensive hub in the new American Southwest. The site, as described by Emory, was “the only point which commands the entire town and which itself is commanded by no other.”

A day earlier, U.S. Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny commanded control of Santa Fe and New Mexico as he marched his 1,500-man army into the centuries-old plaza and hoisted the flag above the palace where the governments of Spain and Mexico had previously reigned. Kearny’s invasion was the third and final occupation of New Mexico by a foreign entity since Spanish soldiers first blazed El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro to claim the province for Spain in 1598. The newest conquest would further transform the cultural and commercial character of the capital of Santa Fe, whose 1610 plaza was the main destination of El Camino Real and the Santa Fe Trail in New Mexico.

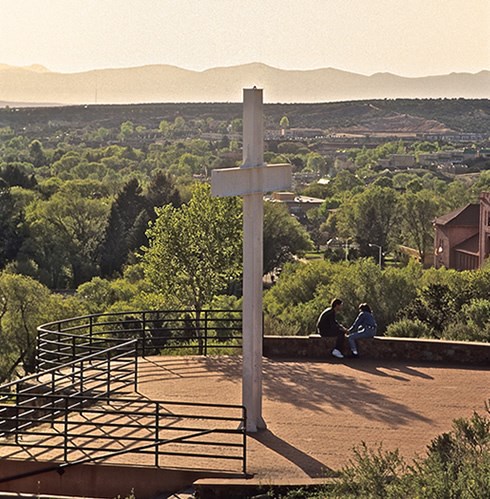

Today’s Fort Marcy ruins, located within the 6.5-acre Prince Park, are a barely distinguishable arrangement of earthen mounds that trace the outline of the fort’s original foundations. Slight indentations encircling the compound in the dirt suggest a once-formidable defensive ditch from which troops could fire from all directions. A partnership between the City of Santa Fe and the National Park Service recently produced a series of new interpretive wayside exhibits that guide visitors through the site. Though the physical experience of the fort now is left largely to the imagination, the elevated vantage point preserves the visual experience of scanning the city center from above.

The Santa Fe Plaza still bustles with civic and commercial activity, maintaining the city’s legacy as an international crossroads of culture and commerce. Other landmarks that stood during the military’s tenure in the city are also easy to spot. Most noteworthy are the Palace of the Governors, the centuries-old seat of government that now serves as part of the state history museum, and the Territorial-era Romanesque Basilica Cathedral of St. Francis, the longtime center of the Franciscan order of the Catholic Church in Santa Fe.

The vision for Gilmer’s Fort Marcy as the first Army installation in the Southwest was to protect soldiers from the possibility of a local uprising. Mexican Governor Manuel Armijo had publicly declared resistance to the occupation, but when faced with Kearny’s manpower at nearby Apache Canyon, Armijo and his troops retreated without a fight. Many New Mexicans who maintained allegiance to Mexico also angrily opposed the occupation, though Kearny’s entry into the city went unchallenged. More than anything, Fort Marcy was a symbolic reminder to residents that U.S. troops were in New Mexico to stay.

Within six days of the Army’s arrival, Fort Marcy began to rise in the skyline. As an eight-foot-deep moat was dug around the fort’s perimeter, the extracted dirt was reserved for building walls that ultimately stood five feet wide and nine feet tall. Precontact pottery shards, stone and other remnants from the site’s centuries of Native occupation were mixed with the dirt and water hauled from below to construct an irregular star-shaped compound featuring a semi-underground gunpowder magazine and an adobe-block guardhouse. When finished, every angle of the fort held all of Santa Fe within view, and within gunshot.

In 1853, Colonel J.K.F. Mansfield called Fort Marcy “the only real fort in the territory,” stating that it is “well planned and controls a city of about 1,000 population.” Nonetheless, its soldiers’ quarters were never occupied and its borders never crossed by enemy fire. Just as soon as the fort was built, its earthen walls began to erode. By late 1846, most fort artillery had been moved to the plaza area, where army activity took place within the 17-acre Fort Marcy Military Reservation—including officials’ headquarters, soldiers’ barracks, a hospital, storehouses, corrals and more.

While its defensive purpose was short-lived, Fort Marcy bore witness to some of the most important cultural transitions in the history of New Mexico and the U.S. The American occupation brought increased flows of international trade goods and traders to Santa Fe, many of whom transported caravans of military supplies. Inexpensive manufactured items from the east proved popular and profitable as they moved into the city along the Santa Fe Trail and south to Chihuahua along El Camino Real, then commonly known as the Chihuahua Trail.

The military’s influence in the expansion of commerce in the Territorial era would prove critical to Santa Fe’s future economic development, especially after the 1848 end of the Mexican-American War and New Mexico’s designation as a U.S. Territory in 1850. By the late 19th century, however, The New Mexican newspaper described the whole of Fort Marcy, including the long-neglected hilltop fort, as “a menace and an eyesore.” While El Camino Real and the Santa Fe Trail lost steam in the path of the new railroad, the military presence in the capital gave way to progress as New Mexicans embraced American ideals and a vision of statehood to come.

Fort Marcy Ruins at Historic Fort Marcy Park is located in downtown Santa Fe, NM. There are wayside exhibits along the perimeter of the park that narrate the history of the fort. Wheelchair-accessible sidewalks allow visitors to move from the parking lot along the perimeter of the site, which includes a series of wayside exhibits that narrate the history of the fort. For more information, visit the Santa Fe Convention and Visitors Bureau website.

Explore more history by visiting the El Camino Real travel itinerary website.