Last updated: November 15, 2021

Article

Water Quality in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Water Years 2016–2018

Overview

The promise of a raft trip, a swim, or a hike through a water-filled slot canyon draws millions of visitors to national parks in Colorado and Utah each year. Water is also the giver of life in these semi-arid ecosystems, helping determine the distribution—and survival—of native plants and animals. But under certain conditions, water can also make people ill, or become incapable of sustaining riparian life. To ensure human safety and environmental health, it’s important to know what conditions are typical in park waters, and what kinds of changes are occurring. That means compiling a scientific record over time.

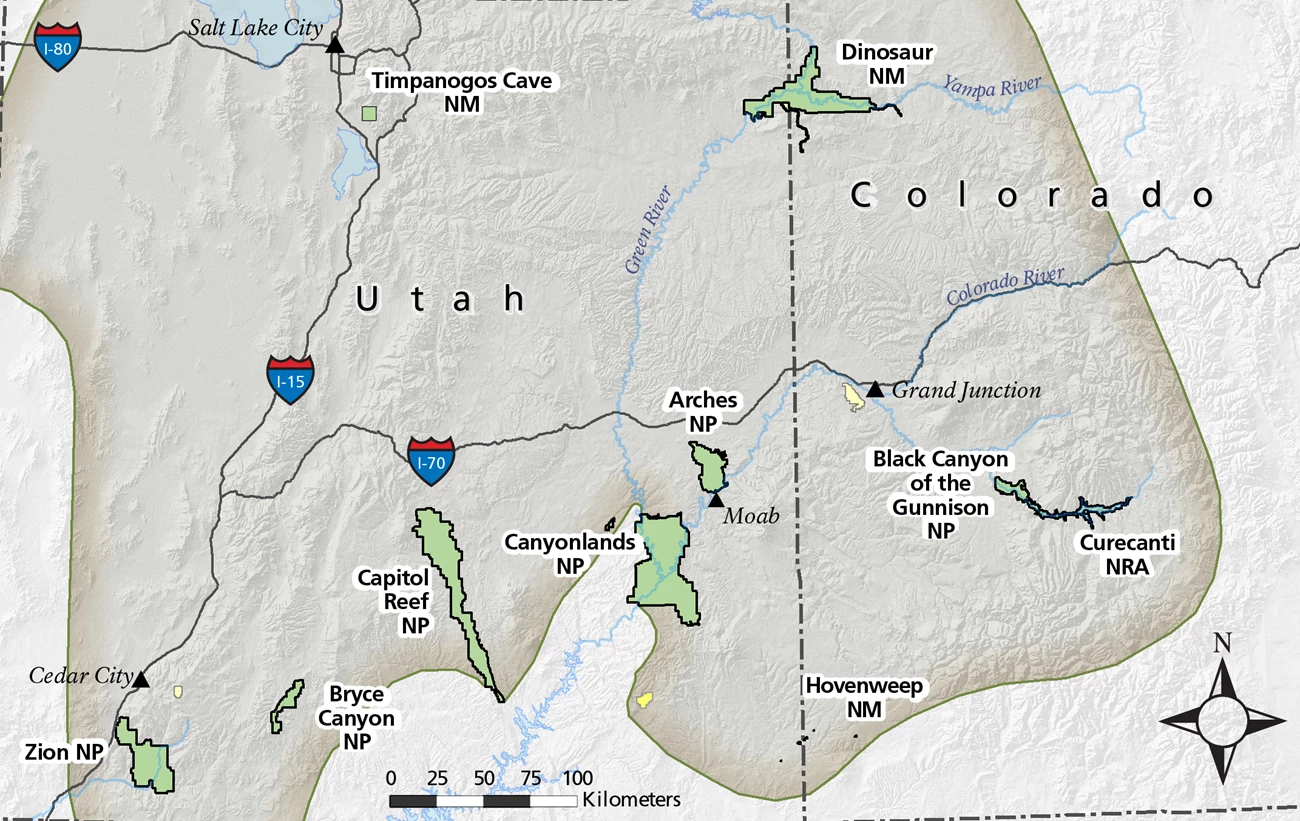

About once a month, ecologists collect water samples at dozens of monitoring sites in and near ten National Park Service units across Utah and Colorado. After the samples are analyzed, the Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) reports the results to park managers. This consistent, long-term monitoring helps alert managers to existing and potential problems.

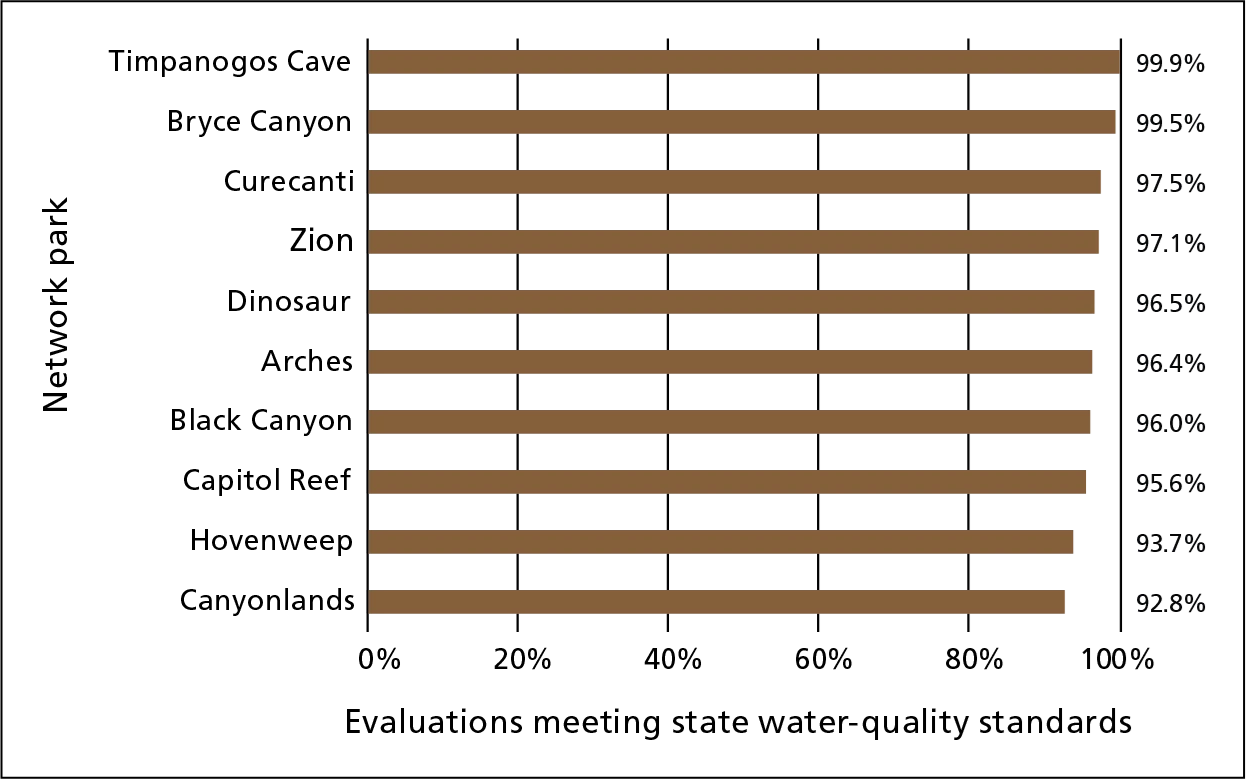

Looking at the results over time can help managers know how they’re doing at addressing those problems—or at maintaining good water quality. A recent report tracked NCPN water quality at 62 different locations on streams, rivers, and reservoirs from October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2018. The results were compared to state water-quality standards. The news was mostly good: Of 18,583 total evaluations completed, 96.8% met state water-quality standards.

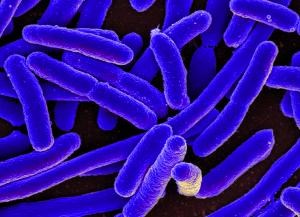

Where standards were not met, the most common exceedances were due to elevated nutrients (such as phosphorus), elevated bacteria (E. coli), elevated water temperature, elevated trace metals, elevated total dissolved solids (and sulfate), elevated pH, and low dissolved oxygen.

Methods

To compile the report, NCPN ecologists worked with staff from individual park units, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the State of Utah to collect and analyze water-quality data from in and near Arches, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Bryce Canyon, Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, and Zion national parks; Dinosaur, Hovenweep, and Timpanogos Cave national monuments; and Curecanti National Recreation Area. As many as 30 parameters are measured at each site visit. Portable sensors were used to measure basic indicators of water quality: specific conductivity, flow, temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen. Field and laboratory measurements were then compared to state water-quality standards to determine if standards were being met and if, over time, conditions were changing.

Image by National Institutes of Health

Issues of Management Concern

E. coli

Escherichia coli (E. coli) are bacteria found in the environment, foods, and intestines of people and animals. Most strains of E. coli are harmless, but others can cause diarrhea, urinary tract infections, pneumonia, and other illnesses. Sites monitored in seven of ten NCPN park units had E. coli exceedances that could be addressed by management actions: Arches, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Bryce Canyon, Capitol Reef, and Zion national parks; Curecanti National Recreation Area, and Dinosaur National Monument. Management actions are already in place at many of these sites; issues with E. coli contamination at Yellow Creek (Bryce Canyon National Park) improved after the park boundary fence downstream of the site was repaired, keeping cattle out of the park.

But some of the actions needed to reduce E. coli in park waters are beyond the control of the National Park Service. Changes to improve water quality often require voluntary participation by private individuals and their respective states. At North Fork Virgin River (Zion NP), E. coli exceedances have been less frequent since the State of Utah worked with landowners and grazing permittees to modify agricultural practices. To further reduce E. coli exceedances at Zion and other parks—and, in turn, improve public health and safety—will require continued cooperation between the National Park Service, state agencies, and local landowners.

Water temperature

Fish, insects, and other aquatic species all have a preferred temperature range. As temperatures get too far above or below that range, aquatic organisms are unable to survive. At least one site in half the parks monitored had elevated temperature levels during the monitoring period. Water temperatures are expected to increase as climate change increases air temperatures and decreases surface-water flows in the U.S. Southwest.

Selenium

Selenium is a trace element essential to nutrition but toxic at high levels. Selenium concentrations in Red Rock Canyon (Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park) continued to exceed the state aquatic-life standard at two sites. Although selenium weathers naturally from bedrock and soils in the Red Rock Creek drainage, upstream irrigation flows could be depositing additional selenium-rich sediments into the creek. Continued management action is needed to bring these flows into compliance with state water-quality standards.

pH

pH is a measure of how acidic or basic water is. A pH that varies too far from neutral can reduce the ability of plants and animals to use a water body. In recent years, pH exceedances have declined at North Creek, in Zion National Park. Only one exceedance for pH occurred during water years 2016–2018, as compared to seven exceedances in water years 2013–2015, and nine exceedances in water years 2010–2012. The reduction in pH exceedances indicates that conditions in North Creek may be stabilizing after a wildfire burned much of the watershed in 2006.

Not All Exceedances Are Cause for Worry

It might sound surprising, but not all water-quality violations are cause for management concern. For instance, nine of ten NCPN park units had elevated phosphorus concentrations in 2016–2018. High levels of nutrients, like phosphorus, can lead to algal blooms and eutrophication—a process in which dense plant growth depletes oxygen in the water, leaving animals unable to survive. However, on the Colorado Plateau, such exceedances are often the result of local geologic processes. This is especially true of phosphorus, which can be introduced into surface water bodies by natural weathering of the geologic strata found throughout the Colorado Plateau. Human activities that increase erosion, such as grazing, logging, mining, pasture irrigation, and off-highway vehicle use, can contribute to higher phosphorus concentrations. But without other signs of impairment (such as low dissolved oxygen levels or eutrophication), naturally occurring phenomena alone do not typically require management action. Continued monitoring, however, is essential.

Information in this brief was summarized from C. Hackbarth and R. Weissinger. 2020. Water quality in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Water years 2016–2018.

Tags

- arches national park

- black canyon of the gunnison national park

- bryce canyon national park

- canyonlands national park

- capitol reef national park

- curecanti national recreation area

- dinosaur national monument

- hovenweep national monument

- timpanogos cave national monument

- zion national park

- ncpn

- northern colorado plateau network

- water quality

- monitoring

- e. coli

- zion national park

- rivers

- river monitoring