Last updated: September 16, 2025

Article

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Golden Spike National Historical Park: 2024 Field Season

NPS/Luke Gommermann

Why Monitoring Matters

Invasive exotic plants (IEPs)—plants that are not native and can quickly spread in new areas—are growing across Golden Spike National Historical Park (NHP). Species like Scotch thistle (Onopordum acanthium) and field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) are widespread and can crowd out native vegetation, degrade wildlife habitat, and change how visitors experience the landscape. These plants disrupt ecosystems and can reduce plant diversity and alter natural plant communities. Monitoring IEPs helps park managers focus control efforts, protect native species, and keep the landscape healthy. This update highlights current trends, high-density areas, and ongoing challenges.

What We Found

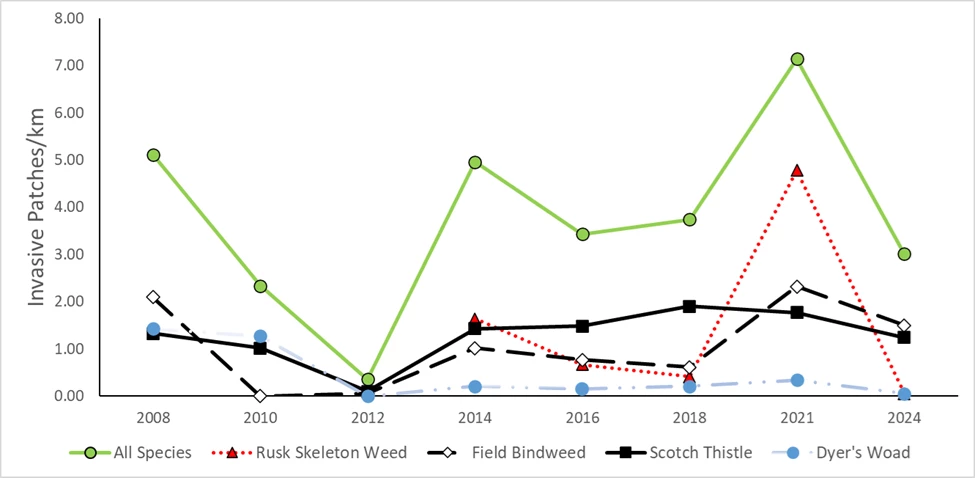

In 2024, Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) crews recorded 60 patches of 6 priority invasive plant species along more than 20 kilometers (12.6 miles) of monitoring routes in the park (Table 1). Field bindweed and Scotch thistle were the most prevalent species (Figure 1). These plants were commonly found along roads, trails, and drainages, areas especially vulnerable to invasion.

| Common Name Scientific name |

Total # of Infestations | 1 to Few Plants | Few Plants– 40 m² |

>40– 400 m² |

>400– 1000 m² |

>1000 m² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rush skeletonweed Chondrilla juncea |

1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| field bindweed Convolvulus arvensis |

29 | 0 | 7 | 22 | 0 | 0 |

| quackgrass Elymus repens |

1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| dyer’s woad Isatis tinctoria |

1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Scotch thistle Onopordum acanthium |

24 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| moth mullein Verbascum blattaria |

4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| jointed goatgrass Aegilops cylindrica |

5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Priority Species, Total | 60 | 7 | 19 | 33 | 1 | 0 |

NPS

Patterns differed across species and sites. The Last Cut Drainage, Facility Road, and Residence Service Road had the highest number of infestations recorded in 2024. In contrast, Witkers Service Road had no priority species detected.

Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) was the most widespread species in transects, present in 32 (82%) of transects. Cover was especially high, averaging 2.47% across all routes.

Russian knapweed (Centaurea repens), previously recorded in the park, was not detected in 2024, suggesting progress in control efforts.

Despite declines in some species, infestations remain in key areas, underscoring the need for continued monitoring and targeted control. Early detections and shifts in species presence highlight the value of ongoing surveillance across Golden Spike’s most vulnerable areas.

How We Collected the Data

Crews surveyed 13 monitoring routes on June 20–21, 2024, covering about 20.3 km (12.6 miles) of roads, trails, and drainages. They recorded invasive plant locations, species, and patch size. Most infestations were found along routes with frequent disturbance. Results from these surveys contribute to long-term trend analyses of invasive patches per kilometer (Figure 2).

NPS/Dustin Perkins

The line graph shows a sharp peak in invasive exotic plant detections in 2021, followed by a decline in 2024. It tracks detections per kilometer across Golden Spike National Historical Park from 2008 to 2024:

- The vertical axis shows invasive patches per kilometer from 0 to 8.

- The horizontal axis shows years in two-year increments from 2008 through 2024.

- The solid green line represents detections of all species combined. It begins at 5 patches/km in 2008, drops to near 0 by 2012, rises steadily to 5 in 2014, dips to 3 in 2016, increases again to nearly 8 in 2021, and then falls to 3 in 2024.

- The red dotted line with triangle markers represents rush skeletonweed. It is absent in most years, rises slightly above 1 patch/km in 2014, dips below 1 in 2016 and 2018, spikes sharply to nearly 5 in 2021, and then falls back to 0 in 2024.

- The black line with diamond markers shows field bindweed. It starts just over 1 patch/km in 2008, dips to 0 in 2010, fluctuates between 0.5 and 2 from 2014 through 2021, and then declines to near 1 in 2024.

- The thick black line with square markers represents Scotch thistle. It begins near 1 patch/km in 2008, rises gradually to about 2 by 2018, remains stable near that level in 2021, and then drops to just over 1 in 2024.

- The light blue line with circular markers represents dyer’s woad. It shows consistently low detections, near or below 0.5 patches/km across all years, with a slight peak in 2008 and values close to 0 in 2024.

Consistent methods were used to estimate how likely it was to detect each plant species in the field. This helps ensure accuracy across different routes and survey teams. Teams walked along each route and documented all visible infestations within a 10–16 meter-wide area. Quadrats were placed at set distances along survey lines to estimate plant cover and soil characteristics.

What Comes Next

Invasive plant densities and species composition differed by route. The Last Cut Drainage, Facility Road, and Residence Service Road had the highest densities of priority invasive plants in 2024, while Witkers Service Road had no detections. Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis) and Scotch thistle (Onopordum acanthium) were the most common priority species, while rush skeletonweed (Chondrilla juncea), dyer’s woad (Isatis tinctoria), quackgrass (Elymus repens), and moth mullein (Verbascum blattaria) were detected only in a few patches, making them good candidates for control. Russian knapweed (Centaurea repens) was not detected in 2024, suggesting success from past control efforts.

Park managers can use these findings to better detect, manage, and prevent the spread of invasive plants at Golden Spike National Historical Park.

Information in this article was summarized from Invasive exotic plant monitoring at Golden Spike National Historical: 2024 field season by D. Perkins. Content was edited and formatted for the web by E. Rendleman.