Last updated: September 12, 2025

Article

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2024 Field Season

NPS/Amy Washuta

Why Monitoring Matters

Invasive exotic plants (IEPs)—plants that are not native and can quickly spread in new areas—are growing across Fossil Butte National Monument (NM). Species like cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) and creeping foxtail (Alopecurus ventricosus) are widespread and can crowd out native vegetation, degrade wildlife habitat, and alter the park’s natural scenery. These plants disrupt ecosystems and reduce plant diversity, including the presence of native pollinators. Monitoring IEPs helps park managers target control efforts, protect native species, and maintain ecosystem health. This update highlights current trends, high-risk areas, and ongoing challenges.

What We Found

In 2024, Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) crews recorded 812 patches of 14 priority invasive plant species along 65.1 kilometers (40.4 miles) of monitoring routes in the monument (Table 1). Cheatgrass and creeping foxtail were the most widespread species. These plants were commonly found along roads and drainages, especially near the Main Park Road, which had the highest infestation density.

| Common Name Scientific name |

Total # of Infestations | 1 to Few Plants | Few Plants– 40 m² |

>40– 400 m² |

>400– 1000 m² |

>1000 m² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| creeping foxtail Alopecurus ventricosus |

240 | 6 | 75 | 123 | 28 | 8 |

| Japanese brome Bromus japonicus |

32 | 1 | 12 | 19 | 0 | 0 |

| cheatgrass Bromus tectorum |

310 | 0 | 44 | 263 | 1 | 2 |

| whitetop Cardaria sp. |

2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| musk thistle Carduus nutans |

19 | 7 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada thistle Cirsium arvense |

24 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| field bindweed Convolvulus arvensis |

1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| common hound’s tongue Cynoglossum officinale |

2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| orchard grass Dactylis glomerata |

1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| flixweed Descurainia sophia |

33 | 6 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| quackgrass Elymus repens |

73 | 3 | 26 | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| black henbane Hyoscyamus niger |

20 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| yellow sweet-clover Melilotus officinalis |

55 | 14 | 16 | 22 | 3 | 0 |

| sowthistle Sonchus sp. |

1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| woolly mullein Verbascum thapsus |

1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 813 | 58 | 231 | 483 | 32 | 10 |

| Priority Species, Total | 812 | 57 | 231 | 483 | 32 | 10 |

Patterns differed across species and sites. Routes like Main Park Road (22.1 patches/km), West Fork Chicken Creek (18.1 patches/km), and Chicken Creek (16.3 patches/km) had the highest infestation densities. In contrast, Eagle Nest Point Road had no priority species detected in 2024.

Cheatgrass was the most widespread species in transects, present in 23 of 137 transects. While it was frequently encountered, its average cover across all transects was relatively low at 0.06%, with slightly higher presence along the Main Park Road.

Some species showed notable changes. Japanese brome (Bromus japonicus) declined sharply from previous years, while common hound’s tongue (Cynoglossum officinale), woolly mullein (Verbascum thapsus), and sowthistle (Sonchus sp.) were detected for the first time since monitoring began in 2008.

Despite progress in some areas, infestations remain concentrated along key routes and disturbed areas, underscoring the need for continued monitoring and targeted control. Early detections and shifts in species presence highlight the value of ongoing surveillance across Fossil Butte’s most vulnerable areas.

How We Collected the Data

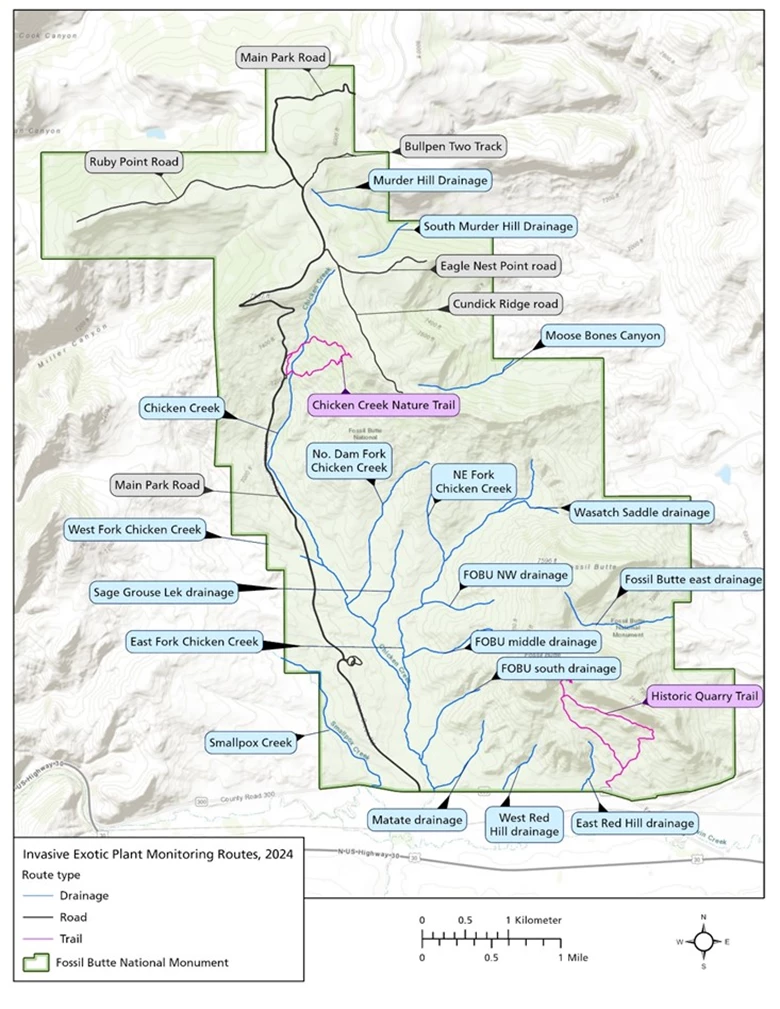

Crews surveyed 25 monitoring routes from June 21–25, 2024, covering approximately 65.1 kilometers (40.4 miles) (Figure 1). They recorded invasive plant locations, species, and patch sizes. Most routes followed roads, trails, and drainages—areas most likely to be invaded due to frequent disturbance.

NPS/Aneth Wight, Eliot Rendleman

Roads and trails shown include the Main Park Road and Ruby Point Road in black and the Chicken Creek Nature Trail and Historic Quarry Trail in purple.

Drainages mapped in blue include Chicken Creek, North Dam Fork, West Fork, East Fork, Smallpox Creek, Matate, Wasatch Saddle, and Red Hill. Additional drainages shown are Moose Bones Canyon, Sage Grouse Lek, Fossil Butte Northwest, Fossil Butte Middle, and Fossil Butte South.

The map legend in the lower left identifies route types with color-coded lines: blue for drainages, black for roads, and purple for trails. The monument boundary is outlined in green. The legend also includes a north arrow, a scale bar in kilometers and miles, and an inset map for location context.

Consistent methods were used to estimate how likely it was to detect each plant species in the field, helping ensure accuracy across different routes and survey teams. Teams walked along each route and documented all visible infestations within a 10–16 meter-wide area, based on the effective detection swath width. Quadrats were placed at set intervals along survey lines to estimate plant cover and soil characteristics.

What Comes Next

Invasive plant densities and species composition differed by route. Main Park Road, West Fork Chicken Creek, and Chicken Creek had the highest densities of priority invasive plants in 2024, while Eagle Nest Point Road had no detections. Cheatgrass and creeping foxtail were the most common priority species, while Japanese brome declined sharply compared to previous years, suggesting progress from ongoing control efforts.

Park managers can use these findings to better detect, manage, and prevent the spread of invasive plants at Fossil Butte National Monument.

Information in this article was summarized from Invasive exotic plant monitoring at Fossil Butte National Monument: 2024 field season by D. Perkins. Content was edited and formatted for the web by E. Rendleman.