Last updated: September 17, 2025

Article

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Colorado National Monument: 2024 Field Season

NPS/Amy Washuta

Why Monitoring Matters

Invasive exotic plants (IEPs)—plants that are not native and can quickly spread in new areas—are growing across Colorado National Monument (NM). Species like yellow sweet clover (Melilotus officinalis) and yellow salsify (Tragopogon dubius) are widespread and can crowd out native vegetation, degrade wildlife habitat, and change how visitors experience the landscape. These plants disrupt ecosystems and can reduce plant diversity and the presence of native pollinators. Monitoring IEPs helps park managers focus control efforts, protect native species, and keep the landscape healthy. This update highlights current trends, high-risk areas, and ongoing challenges.

What We Found

In 2024, crews recorded 955 patches of 14 invasive plant species along more than 70 miles of monitoring routes in the monument (Table 1). Yellow sweet clover, yellow salsify, and ripgut brome (Anisantha diandra) were the most widespread species (Figure 1). These plants were commonly found along roads, canyon bottoms, and other disturbed areas.

| Species | Total Infestations | No Size Class Recorded | 1 to 3 Plants | 3 Plants–40 m² | 40– 400 m² |

400– 1000 m² |

>1000 m² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acroptilon repens | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anisantha diandra | 86 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 73 | 2 | 0 |

| Asparagus officinalis A | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Breea arvensis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Carduus nutans | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Chorispora tenella | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Cirsium vulgare | 11 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Convolvulus arvensis | 37 | 5 | 0 | 25 | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| Cylindropyrum cylindricum | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Elaeagnus angustifolia | 25 | 22 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Halogeton glomeratus | 29 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| Melilotus officinalis | 448 | 32 | 0 | 73 | 221 | 97 | 25 |

| Populus alba A | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tragopogon dubius | 253 | 63 | 0 | 111 | 71 | 8 | 0 |

| Triticum aestivum A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ulmus pumila | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Verbascum thapsus | 43 | 6 | 0 | 10 | 25 | 2 | 0 |

| Priority Species, Total | 959 | 162 | 0 | 250 | 405 | 116 | 26 |

NPS/Amy Washuta

Patterns differed across species and sites. Many routes—including Ute Canyon, East Glade Park Road, and Red Canyon—had the highest number of infestations recorded since monitoring began in 2009. Russian knapweed (Acroptilon repens) and musk thistle (Carduus nutans) were detected for the first time during this survey.

Cheatgrass (Anisantha tectorum) was the most widespread species in transects, present in more than 80% of transects. Cover was especially high in Wedding Canyon, Fenceline, and Ute Canyon.

Tamarisk (Tamarix sp.), which has been a management focus for years, was not found in 2024, showing progress in control efforts.

Despite declines in some species, the overall increase in infestations at key routes underscores the need for continued monitoring and targeted control. Early detections—such as musk thistle and Russian knapweed—highlight the value of ongoing surveillance across the monument’s most vulnerable areas.

How We Collected the Data

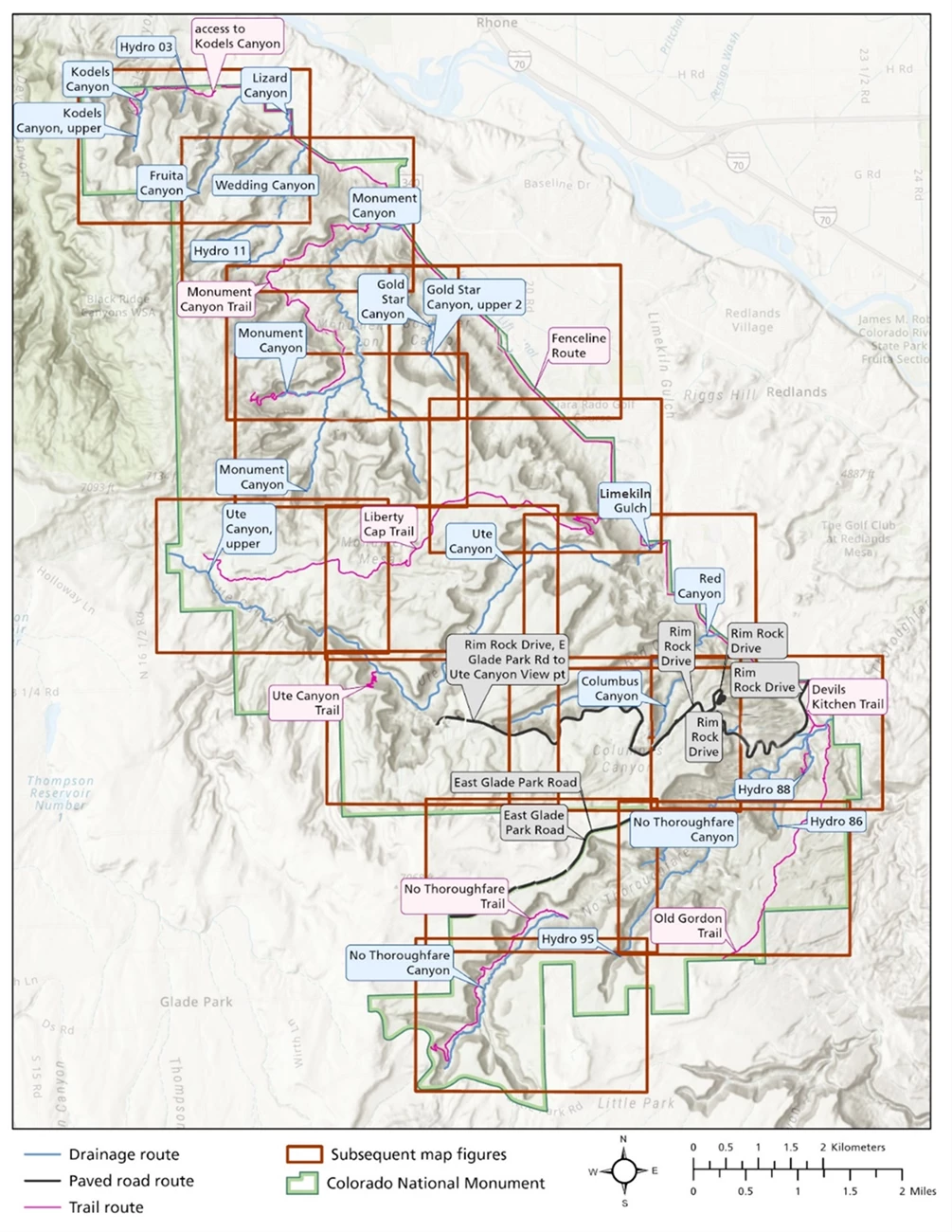

Crews surveyed 25 monitoring routes from June 5–12, 2024, covering about 113.8 km (70.7 miles) (Figure 2). They recorded invasive plant locations, species, and patch size. Most routes followed roads, canyons, or other areas with frequent disturbance.

Consistent methods were used to estimate how likely it was to detect each plant species in the field. This helps ensure accuracy across different routes and survey teams. Teams walked along each route and documented all visible infestations within a 10-meter-wide area. Quadrats were placed at set distances along survey lines to estimate plant cover and soil characteristics.

NPS/Aneth Wight, Eliot Rendleman

A shaded relief map of Colorado National Monument with drainage, road, and trail routes surveyed for invasive exotic plants during June 5–12, 2024. The park boundary is outlined in green. Drainage routes are shown in blue, paved road routes in black, and trail routes in purple. Prominent locations labeled include Rim Rock Drive, Ute Canyon, No Thoroughfare Canyon, East Glade Park Road, Devils Kitchen Trail, Liberty Cap Trail, and several “Hydro” sites. Orange boxes indicate areas shown in greater detail in subsequent figures.

The map legend in the lower left identifies route types with blue for drainages, black for paved roads, and purple for trails, along with orange for subsequent figures. A north arrow and scale bar in kilometers and miles are also included.

What Comes Next

Invasive plant densities and species composition differed by route. Ute Canyon, East Glade Park Road, and Red Canyon had the highest densities of invasive plants, including many of the largest infestations recorded since monitoring began in 2009. Russian knapweed and musk thistle were newly detected, while tamarisk was absent for the first time, suggesting progress from past control efforts.

Park managers can use these findings to better detect, manage, and prevent the spread of invasive plants at Colorado National Monument.

Information in this article was summarized from Invasive exotic plant monitoring at Colorado National Monument: 2024 field season by D. Perkins. Content was edited and formatted for the web by E. Rendleman.