Last updated: December 11, 2023

Article

Riparian Health on the Fremont River, Capitol Reef National Park, 2009–2021

Fremont River, Capitol Reef National Park.

Key points

- The potential for lower inputs and greater evapotranspiration suggest the Fremont River is at risk for progressively lower flows over time. Peak flows showed the greatest decreases.

- Flooding was infrequent at the monitored reach, inhibiting cottonwood recruitment. But groundwater levels remained shallow enough to support mature cottonwood trees.

- Thalweg surveys showed that stream channels were either stable or increasing in elevation at all monitored reaches.

- Riparian vegetation was characteristic of a Fremont cottonwood woodland at three reaches. The abandoned oxbow has transitioned to an upland system.

Background

Where streams and rivers flow, riparian areas are oases of life in arid and semiarid landscapes. They are biologically diverse and perform important ecosystem services. Riparian vegetation helps clean excess nutrients and sediment from surface runoff and shallow groundwater. It also shades streams, optimizing light and temperature for aquatic plants, fish, and other animals. Linked to both aquatic and terrestrial systems, riparian ecosystems are potentially sensitive indicators of landscape-level change.

Human activities can disrupt these systems. Stream damming or diversion, channel-stabilization structures, invasive exotic species, livestock grazing, timber harvesting, agricultural clearing, groundwater pumping, and trail creation can all influence downstream riparian ecosystems.

To evaluate the health of riparian systems, the Northern Colorado Plateau Network (NCPN) monitors physical and biological attributes of wadeable streams. These include hydrology (including flood frequency), channel shape and composition (geomorphology), and vegetation. Together, these indicators can tell us about “normal” conditions and also give park managers early warning of potential problems.

At Capitol Reef National Park, the network monitors four reaches of the Fremont River (see table and photo gallery). This article summarizes findings and management recommendations from monitoring conducted on these reaches from 2009 to 2021.

Table 1. Locations of monitoring reaches, and parameters monitored on the Fremont River, Capitol Reef National Park.

| Reach | Location | Monitored parameters |

|---|---|---|

| F-01 | Approximately 2.5 kilometers upstream of a knickpoint (sharp change in channel slope) and associated waterfall that emerged following construction of State Highway 24 in 1964 | Geomorphology, vegetation, hydrology |

| F-07 | In a large oxbow that was cut off due to the highway construction | Geomorphology, vegetation |

| F-04 | Approximately 1.5 kilometers downstream of the knickpoint | Geomorphology, vegetation |

| F-14 | Approximately 4.8 kilometers downstream of the knickpoint | Geomorphology, vegetation |

Findings

Hydrology

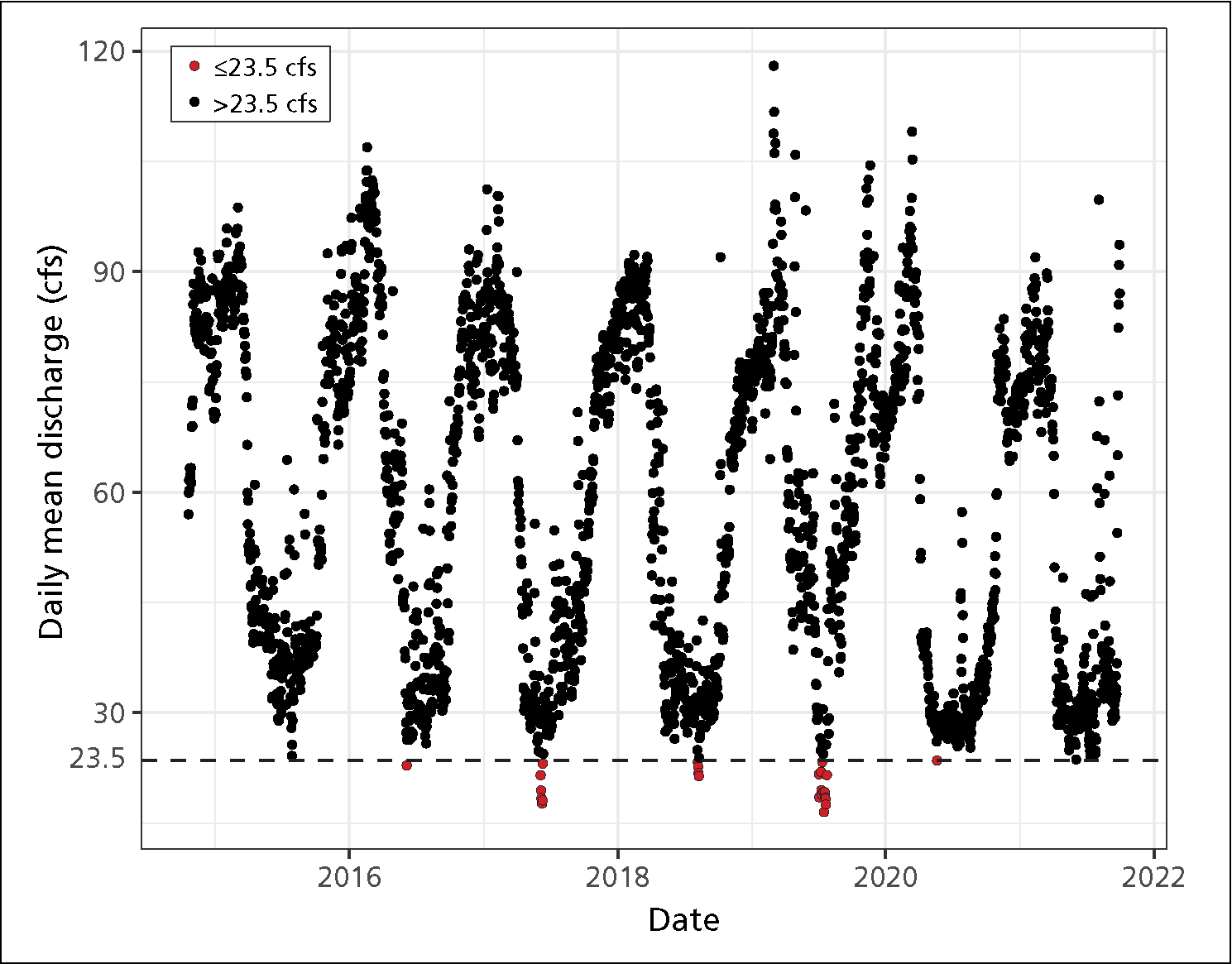

Perennial flows on the Fremont River were maintained during the monitoring period, with a strong seasonal signal corresponding to the irrigation season (April 1–October 31). Daily mean discharge at monitoring reach F-01 ranged from 16.5 to 118 cfs (cubic feet per second), with a median value of 60 cfs. Twenty-five days in the discharge record had a daily mean discharge below 23.5 cfs, the contemporary cumulative water right for downstream water users. All of the daily mean discharges below this threshold occurred during the irrigation season. Lower flows during the irrigation season were a result of both anthropogenic withdrawals (irrigation) and natural processes (increased evaporation and water use by plants due to higher seasonal temperatures).

Daily mean discharge above and below 23.5 cfs (the contemporary cumulative water right for water users downstream of the park boundary) at the F-01 (above the knickpoint) monitoring reach, WY2015–2021.

During the non-irrigation season, daily mean discharge at the Bicknell gage (USGS gaging station 09330000, approximately 34 kilometers upstream of reach F-01) is a fairly good predictor of daily mean discharge at the F-01 monitoring reach. Daily mean discharge at the Bicknell gage decreased from WY2001 to WY2021.

Overbank flows at reach F-01 were infrequent, generally as brief events associated with intense monsoon storms in the late summer and fall. Cottonwood recruitment is generally tied to spring overbank-flow (flooding) events that receded slowly, supporting seedling establishment. At reach F-01, overbank flows do not have the necessary timing or duration to support cottonwood recruitment on higher floodplain surfaces. However, groundwater levels averaged about two meters below the surface, well within the <4-meter threshold that supports mature cottonwood trees. Only legacy cottonwood trees remain on these surfaces, but they actively resprout following disturbances, such as beaver browsing.

The potential for lower inputs and higher air temperatures, leading to greater evapotranspiration, suggest the Fremont River is at risk for progressively lower flows over time, as is projected for surface waters throughout the US Southwest due to anthropogenic climate change.

View of F-01 (above the knickpoint) transect 1 looking upstream, May 2020.

Geomorphology

In reaches F-01 and F-14, deposition of up to one meter occurred in the floodplain over the monitoring period. Across all reaches, deposition was generally greatest between 2009 and 2014. Only localized erosion occurred; thalweg surveys (measuring the deepest part of a reach transect) showed stream channels were either stable or increasing in elevation. Periods of the greatest sediment deposition and erosion appeared to correspond with peak flows, as observed in the hydrologic record. Reach F-07 (the abandoned oxbow, where there is no flow) was an exception; almost no deposition or erosion took place there.

Vegetation

Vegetation monitoring showed that reaches F-01, F-04, and F-14 are representative of mature riparian systems in the arid Southwest, dominated by a Fremont cottonwood (Populus fremontii) overstory and a mixed-shrub understory. Vegetation cover was dense in reaches F-01 and F-14—close to or above 40% in some years. Historical photos show cottonwood (and willow) species nearly absent from the Fremont River corridor in the early 1900s, but these species are now abundant.

Left image

Historical photo looking northwest up the Fremont River in 1950.

Credit: NPS/Charles Kelley

Right image

The same stretch of river in 2022. The wide, braided river channel greatly narrowed and incised since 1950. Previously unvegetated streambanks are now stabilized primarily by coyote willow and common reed.

Credit: NPS/Rebecca Weissinger

Native species

Native species dominated plant cover in reaches F-01, F-04, and F-14. Riparian obligate species and mixed-age classes of Fremont cottonwood were present, but recruitment of young cottonwoods into larger size classes was limited. The presence of only legacy cottonwood trees on higher floodplain surfaces may limit the system’s resilience to disturbance.

Reaches F-01, F-04, and F-14 had similar cover of obligate wetland species (species found only in wetlands), but reach F-14 had greater cover of facultative wetland species (species that may be found in wetlands or uplands areas), including Fremont cottonwood, scratchgrass (Muhlenbergia asperifolia), and horsetail (Equisetum sp.). In reaches F-01 and F-14, obligate wetland species decreased to their lowest point in the monitoring period in 2021.

Mature cottonwood along the Fremont River.

As the dominant native tree species in large and small river reaches throughout the Colorado Plateau, Fremont cottonwood play a critical role in structuring riparian communities. At NCPN monitoring reaches, densities of Fremont cottonwood were at the lower reported range for mature stands (50–400+ trees per hectare). Maintenance of these cottonwood forests depends on periodic recruitment, which requires large flood events that deposit fresh alluvium, followed by continued availability of adequate soil moisture. Park staff have made efforts to protect growing cottonwoods by wrapping them with chicken wire. However, field crews also noted that some of these fast-growing trees were now being girdled by chicken wire.

Reach F-07, the abandoned oxbow (seen here in 2012), has transitioned to an upland system.

Reach F-07, located in the abandoned oxbow, had distinctly different vegetation than the other reaches. Here, forbs and shrubs that were primarily upland or facultative upland species dominated. These species included rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnus nauseosus), four-wing saltbush (Atriplex canescens), and non-native Russian thistle (Salsola sp.). Trees and ferns were totally absent from the cross-sectional transects in reach F-07, which has transitioned to an upland system. There has been a complete loss of riparian obligate species at this reach, and an almost complete loss of cottonwood trees. It also has a relatively high proportion of exotic species compared to the other reaches.

Exotic species

Vegetation in reaches F-01, F-14, and F-04 had low cover of exotic species (<10% in all years). Control of Russian olive (Eleagnus angustifolia) has had visible impacts in these monitored reaches, where density of Russian olive saplings decreased over time. Tamarisk (Tamarisk sp.) cover was also low in the monitored reaches, likely due to previous control efforts and the presence of the tamarisk beetle (Diorhabda spp.).

But in reach F-07, exotic-species cover ranged from 9% to 25%. In 2009–2011, exotic plants comprised the majority of total cover in this reach. In 2011, the cover of annual grass at reach F-07 increased from <1% to 10%, due to a flush of cheatgrass. Cheatgrass cover remained high 10 years later.

Overall, nine species on the park’s invasive plant priority list were also detected in the monitoring reaches: tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus altissima), asparagus (Asparagus officinalis), blue mustard (Chorispora tenella), bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare), Russian olive, quackgrass (Elymus repens), African mustard (Malcolmia africana), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), and tamarisk (Tamarisk sp).

Management Recommendations

Based on the findings from this monitoring, the NCPN recommends consideration of the following management actions for the Fremont River and its associated resources in Capitol Reef National Park:

- Advocate for maintaining spring-snowmelt flows of 94 cfs or greater in the NCPN monitoring reach where hydrology is monitored (F-01). Policy goals to achieve this could include excluding additional upstream reservoirs and diversions and maintaining the state-managed irrigation season, which currently begins on April 1.

- If a high-accuracy discharge record is desired, then investigate the placement of a gaging station within the park, or the re-establishment of the Caineville gaging station downstream of the park boundary.

- Protect young cottonwoods from beaver herbivory and release older mature trees from chicken wire if it is restricting growth. Remove chicken wire from cottonwoods that have grown and are being girdled.

- Continue control of the woody exotic species, Russian olive and tamarisk.

- Advocate for restoration of the abandoned oxbow, where riparian function has been lost.

Information in this article was summarized from C. Livensperger, Riparian Monitoring of Wadeable Streams on the Fremont River, Capitol Reef National Park, 2009–2021. Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR—2023/2584. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado. https://doi.org/10.36967/2301391.

Tags

- capitol reef national park

- ncpn

- northern colorado plateau network

- northern colorado plateau

- fremont river

- rivers

- river

- riparian

- riparian communities

- riparian ecosystems

- riparian vegetation

- cottonwood

- cottonwood tree

- riparian habitat

- plants

- hydrology

- geomorphology

- utah

- wadeable stream monitoring

- inventory and monitoring

- climate change

- monitoring