Last updated: April 10, 2025

Article

Riparian Vegetation Response to Flow Modification: Water Management Impacts in Canyonlands National Park

NPS/ A. Washuta

Desert Oases: Rivers in the Intermountain West

Rivers are vital, but limited, resources in the semiarid and arid intermountain west for people and for the ecosystems- wildlife and habitats- that depend on them. Local ecosystems evolved based on seasonal water replenishment by early summer snowmelt when pulses of water would flush channels and inundate lowlands, redistributing sediment, nutrients, and water along riverbanks. This resulted in the creation and continued maintenance of a complex river system and diverse riparian corridor. These corridors are zones of vegetation that provide several ecosystem services including helping to maintain water quality, stabilizing banks, and providing habitat that results in biodiversity hotspots and recreational and scenic opportunities for people.

These waterways also attracted human settlements and were key to the development of the western United States. Western expansion brought increased demands for water and electricity, necessitating water management and water development projects such as the Flaming Gorge and Blue Mesa Dams that were installed in the Upper Colorado River Basin in the 1960s. However, the reliable, year-round water supply and hydroelectric power they provided came at a cost to the rivers themselves as changes in streamflow (such as smaller peak flows and higher base flows) resulted in vegetation encroachment, channel narrowing, and the simplification of river morphology including the disconnection of the river from its floodplain.

Water Management in Action: Finding the Balance

In an effort to reduce the negative impacts the flow changes caused in aquatic and riparian ecosystems downstream of the Flaming Gorge and Blue Mesa Dams, dam managers modified reservoir releases in 1992 to simulate more natural flow patterns by managing for lower base flows and higher peak flows. Additional modifications occurred in 1995 to protect endangered fish under the Endangered Species Act, and for a water right put in place on the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park in 2008. These effectively resulted in three different hydrological periods during the 20th and early 21st centuries:

Pre-dam flow: 1940-1966 (before the dams were closed and operating)

Post-dam flow: 1966-1992 (Colorado River) and 1963-1992 (Green River) (dam flows were operated strictly for hydropower)

Post-dam environmental flow: 1992-2022 (flows were modified for habitat and endangered species conservation)

Our Study

We wanted to understand how the initial dam installations and later modified dam management affected riparian vegetation downstream of the Flaming Gorge and Blue Mesa Dams in Canyonlands National Park.

Methods

Using available aerial imagery from 1940 to 2022 we examined vegetated area (defined as having >50% vegetation cover) along three sections (94 mi (152km)) of the Colorado and Green Rivers within Canyonlands National Park to identify changes in riparian vegetation response over 80 years of dam management for the Colorado and Green Rivers and to assess the rate of changes in total vegetation resulting from long-term channel narrowing during the 30 years that the dams were operating with altered (environmental) flows (1992-2022). Our study focused on three river sections in the Upper Colorado River Basin and included both the Green and Colorado Rivers above their confluence and the Colorado River below the confluence (called the Cataract Canyon reach). This represents the cumulative total of the seminatural flow of these rivers before entering Lake Powell (3 mi (5km)) downstream of our study location).

NPS

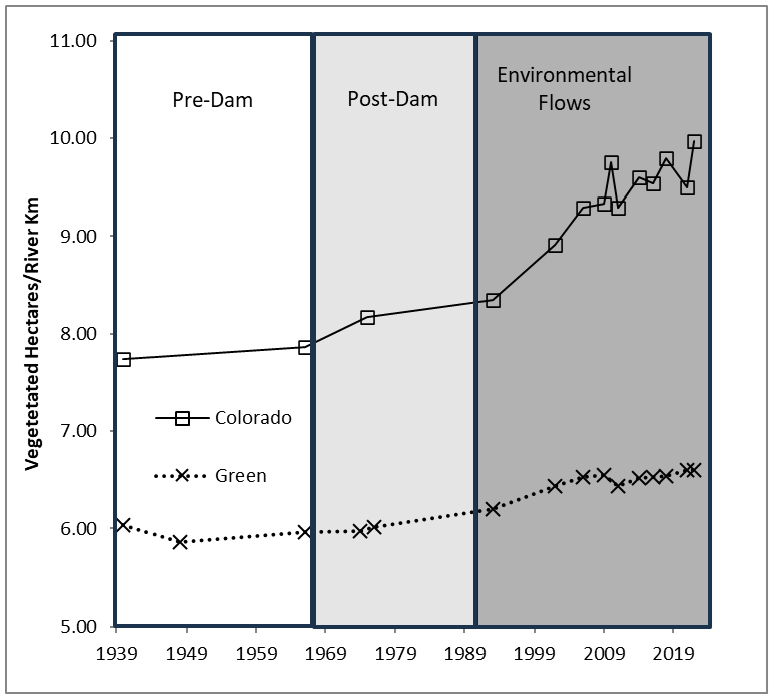

In each year of imagery, we calculated the total vegetated area for the river corridor within the park. We evaluated vegetation change for the three time periods: the pre-dam period of 1940 to 1966, the post-dam period of 1967 to 1992, and the environmental flows period from 1993 to 2022.

Results

Overall, from 1940-2022, vegetated area increased and channels narrowed as new vegetated areas replaced what was formerly channel on the Green River and the Colorado Rivers above the confluence with the Green River. A combination of river regulation, invasion of non-native plants such as tamarisk, decreased peak flows, and increased base flows are likely to have contributed to these changes. Overall, there has been a 28.8% increase in riparian vegetation in the reaches on the Colorado River above Cataract Canyon and a 9.4% increase on the Green River. The vegetated area in these reaches stayed relatively constant in the pre-dam period, from 1940 to 1966. There was actually slightly less vegetated area in 1966 than 1940 on the Green River demonstrating relatively little change to the vegetated area in the pre-dam era. Vegetation Increases were observed during the post-dam flow period (1966-1992) in vegetated areas on the Colorado River above the confluence (6.1% overall, 0.2%/year) and the Green River (4.0% overall, 0.2%/year) as well as during the environmental flows period, from 1993-2022, 19.5% (0.7%/year) on the Green River and 6.5% (0.2%/year) on the Green River. This increase was rapid on these two reaches in the first 13 years from 1993 to 2006, but the rate slowed from 2006 to 2022 when there was a large peak flow in 2011.

The Cataract Canyon reach on the Colorado River below the confluence stayed relatively constant with only a small increase in vegetated area since 1948 and has been relatively stable since 1966. In this reach, the vegetated zone is narrow and changes in vegetated area are small. This is likely because of the difference in geomorphology in this reach compared to the upper reaches. Cataract Canyon’s topography is steep and the river itself has a high gradient and narrow channel. In addition, the high channel gradient is swift enough to remove encroaching vegetation, even with the observed decreases in peak flows.

NPS

The modified environmental flow regimen that began in 1992 on the Green and Colorado rivers decreased but did not reverse the trend of decreasing peak flows. As peaks have declined, there have continued to be increases in vegetated area on the Colorado and Green River from 1993 to 2022. Environmental flows have not yet been able to reverse channel narrowing that has occurred, nor overcome lower annual flows to slow the increase in vegetated area. However, individual large peak flows such as the one that occurred in 2011, can be effective in reducing vegetated areas. The 2011 peak flow, the largest peak flow in the environmental flow period on the Green River and the second largest peak flow on the Colorado River, resulted in a decrease in vegetated area along all three river reaches. This was followed by an increase in vegetated areas to levels similar to pre-2011 flood levels.

Conclusion

Natural resource management often requires consideration of a delicate balance of uses, particularly when water, a requirement for all life, is involved. Science-based decision-making helps managers develop and reach sustainability goals to ensure water is available to meet critical needs for people and ecosystems. Environmental releases, combined with a large peak flow in 2011 have slowed but not reversed the effects of the dams. Large periodic peak flows combined with releases that mimic natural hydrographs are essential to minimize channel narrowing.

Information in this article was summarized from: Riparian Vegetated Area in Pre‐Dam, Post‐Dam, and Environmental Flow Periods in Canyonlands National Park From 1940 to 2022 - Perkins - River Research and Applications - Wiley Online Library https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.4395