Last updated: November 29, 2024

Article

Dwindling Numbers Spur a New Approach to Northern Spotted Owl Monitoring

NPS Photo/Galloway

SEPTEMBER 2023

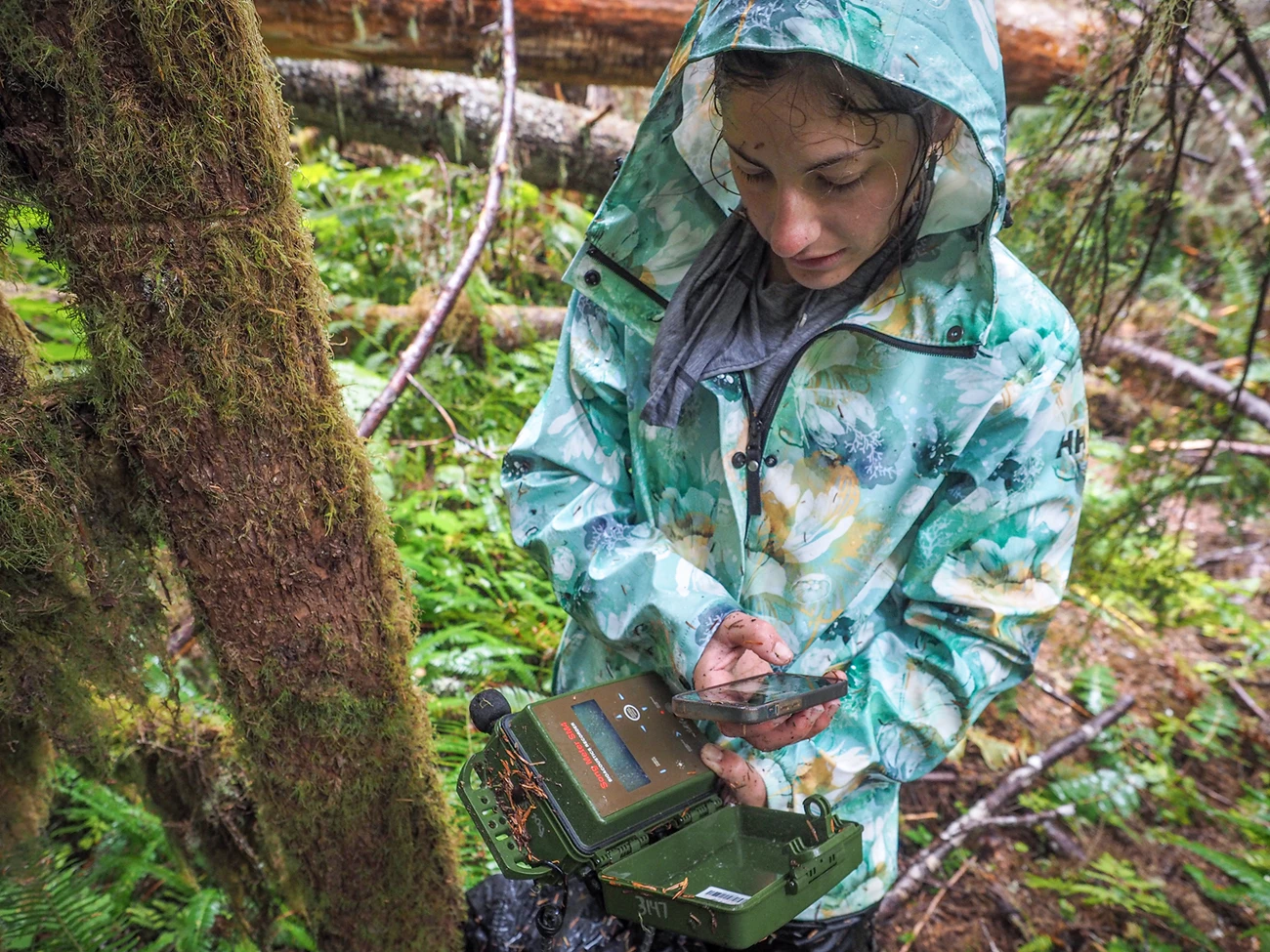

With practiced agility, Makenzie Groves scrambles down a muddy hillside that best resembles a giant pile of tree-sized pickup sticks. In Mount Rainier’s Carbon River Rainforest in late September, rain-soaked ferns and the glossy salal leaves rise to waist height. Scooting under and crawling over windfall trees, Makenzie pauses to check a handheld GPS. Somewhere nearby is the object of her search: a new chapter in the park’s efforts to monitor threatened northern spotted owls.

Over the past five years, autonomous recording units, or ARUs, have become the front line of northern spotted owl monitoring across the species’ range. Beginning in the 1990s, research teams in Olympic, Mount Rainier, and North Cascades used calls played from speakers to provoke territorial responses from real owls. They banded individuals and identified nest trees and breeding pairs, returning to check on them year after year. After years of monitoring, some researchers mastered the art of making pitch-perfect hoots themselves that drew replies from the treetops.

NPS Photo

It's rare to hear a spotted owl hoot today. Populations on the Olympic Peninsula fell by over 80% between 1995 and 2017. In Mount Rainier National Park, they declined nearly 75% over the same period; by 2017, just 18 territorial adults were found across over 80,000 acres of habitat.

While extensive logging of spotted owl habitat prompted the species to be listed as federally threatened in 1990, that’s not the chief threat to owls living within national park boundaries. Instead, declines in protected forests arrived on the wings of a new neighbor: nonnative barred owls.

NPS Photo

Voracious and undiscriminating eaters, barred owls hunt their way through spotted owl prey populations. “They eat a lot of insects. They eat salamanders. They eat everything. And they're certainly having a huge ecosystem impact,” said wildlife biologist Scott Gremel, who has been studying spotted owls in Olympic since the 1990s. “We had an estimate of 230 pairs of spotted owls here in protected habitat—thought we were doing great. And now due to barred owls, they're almost gone.”

Shortly after northern spotted owls were listed as threatened, the multi-agency Northwest Forest Plan was launched. It covers 24 million acres across agency boundaries, with the goal of addressing management needs and protecting threatened species habitat. It also coordinates spotted owl monitoring throughout their range.

2020 marked the transition to what scientists call “phase II.” Implementing a strategy outlined when the Northwest Forest Plan spotted owl monitoring program was established, as owl numbers dwindled scientists phased out callback surveys, deploying ARUs in the same areas with a two-year overlap in methods. As of 2023, all study areas have moved to passive acoustic recording. Now instead of calling out to owls, we are simply listening.

Figure from the 2022 Bioacoustics Annual Report, USDA Pacific Northwest Research Station and NPS Pacific West Region.

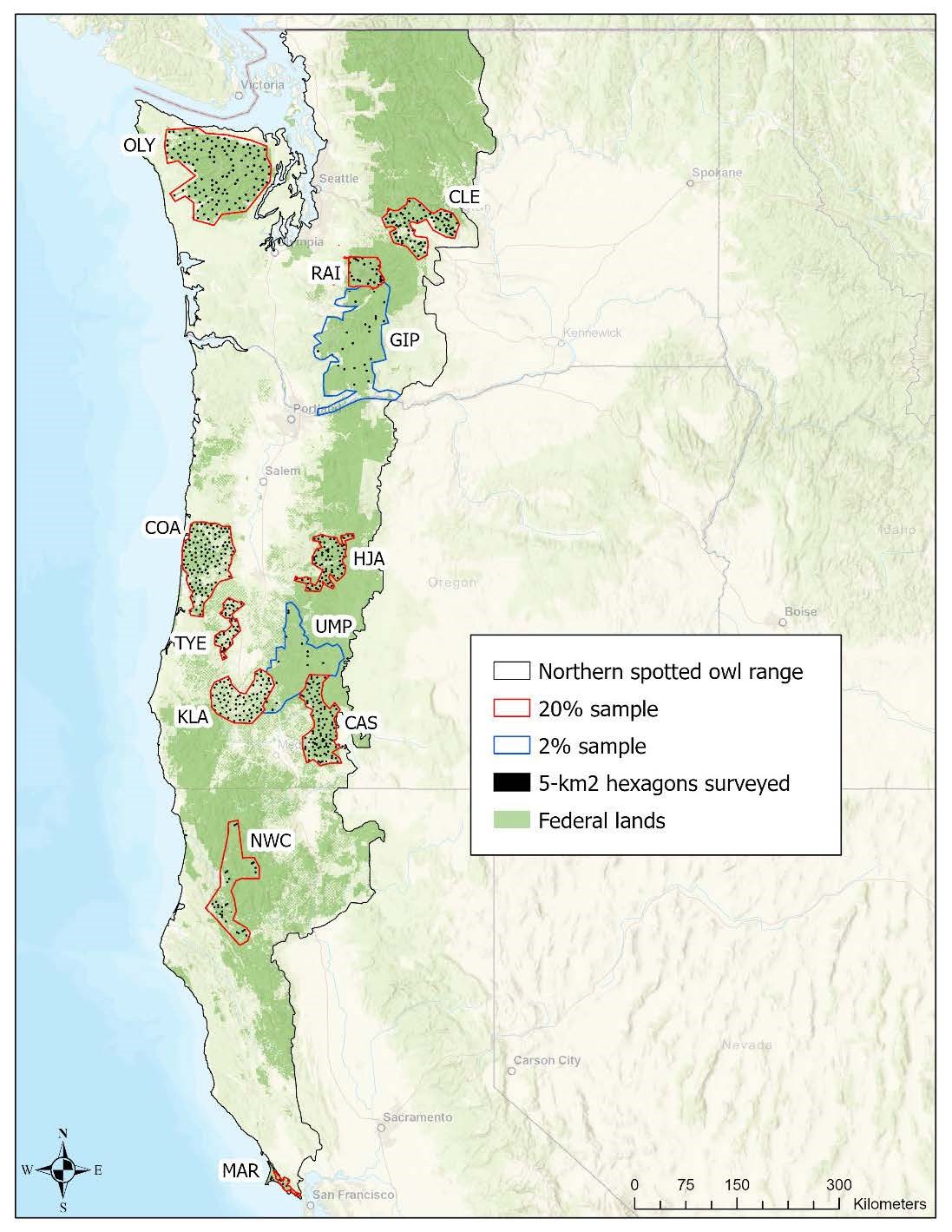

A map of the northwestern US showing the range of the northern spotted owl outlined in black. The range reaches north to the Canadian border, south almost to San Francisco, west along the Pacific Coast, and east into the Cascade Range.

Ten study areas (outlined in red) represent areas where 20% of the possible hexagon-shaped study sites were monitored with passive acoustic monitoring. All 20% sample areas overlapped with historical northern spotted owl demographic study areas. Two additional study areas (outlined in blue) represent the 2% sample areas which were monitored in 2022. Researchers plan to monitor all federal forests within the northern spotted owl range at the 2% level in coming years.

Each area contains black dots indicating the location of passive acoustic monitoring hexagons in 2022.

20% Sample Areas:

- OLY: Olympic Peninsula

- CLE: Cle Elum

- RAI: Mount Rainier National Park

- COA: Oregon Coast Range

- HJA: HJ Andrews

- TYE: Tyee

- KLA: Klamath

- CAS: South Cascades

- NWC: Northwest California

- MAR: Marin County

2% Sample Areas:

- UMP: Umpqua National Forest

- GIP: Gifford Pinchot National Forest

Like a wayward puzzle piece, Makenzie lays eyes on the green plastic box strapped to a small tree at chest height. Carefully unwinding the bungee cords, she flips the unit open to record data on a smartphone, then tucks it safely into her mud-streaked backpack for the journey out. Later, in a lab at Oregon State University, hundreds of hours of audio from the unit’s SD card will be analyzed by a machine learning model trained to pick out spotted owl calls amid the hubbub of the forest.

NPS Photo/Galloway

The transition to ARUs has some serious advantages: First, they are infinitely patient. Each day in their six-week tour of duty, they listen for four-hour intervals at daybreak and dusk, plus 10-minute blocks every hour. And they cover a lot of ground. Four ARUs are deployed in each hexagon-shaped 5 km2 site; these randomly distributed hexagons cover 20% of suitable spotted owl habitat in study areas where teams conducted callback surveys in the past.

But that vast quantity of data does not come without a cost. In 2022 alone, the 96 ARUs in Mount Rainier recorded a total of over 50,000 hours of audio. On the Olympic Peninsula, 474 units captured over 30 years’ worth. The task of analyzing this data using a sophisticated computer program will involve continued refinement as experts check the model’s work. And with new research methods come new questions to answer: How many hoots means a territory is occupied by a nesting pair? How should numbers of female owls, which are less vocal, be most accurately estimated?

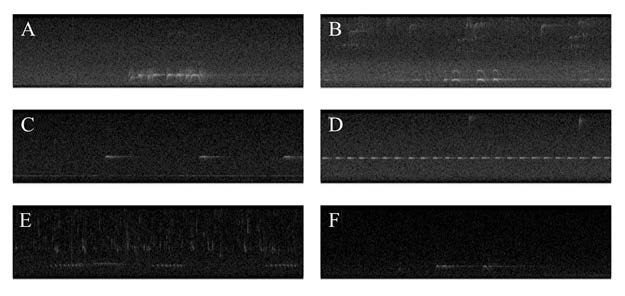

A: barred owl, B; great horned owl, C: northern pygmy owl, D: northern saw-whet owl, E: western screech owl, F: northern spotted owl.

Ruff, Z. J., D. B. Lesmeister, L. S. Duchac, B. K. Padmaraju, and C. M. Sullivan. 2020. Automated identification of avian vocalizations with deep convolutional neural networks. Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation 6:79-92.

Like any hot mic in a crowd, ARUs pick up juicy conversations regardless of speaker. The machine learning model searches for 35 other species, including threatened marbled murrelets. It also flags calls from barred owls, offering new ways to understand their relationship with their smaller cousins. “Where do we not pick [barred owls] up, or where do we pick them up less?” said Scott. “What's the spatial overlap between the two species vocalizing? There's going to be a ton of interesting information we didn't have before.”

NPS Photo/Galloway

Three members of Mount Rainier’s wildlife crew bike out the washed-out Carbon River Road through a light rain, retrieved ARUs bungee-corded tightly to rear cargo racks. These are the final units to be pulled out following the second year of acoustic monitoring in the park. 70 miles northwest, researchers on the Olympic Peninsula are wrapping up their sixth year of acoustic monitoring. North Cascades deployed its first ARUs in 2023 as part of a lower-intensity group of study areas (just one in 50 hexagons of suitable habitat are monitored, versus one in five).

It will be months before scientists know whether any of the ARUs retrieved from the Carbon River in late September contain the distinctive four-part hoot. But new methods alone cannot alter the fact: Spotted owls are in trouble. Of the 96 individual ARUs deployed in Mount Rainier in 2022, only four testified to the continued presence of spotted owls within park boundaries.

As biologists prepare to deploy ARUs for a new season of monitoring, tough questions loom on the horizon. What does stewardship look like for northern spotted owls, faced with an existential threat within the boundaries of national parks themselves?