Last updated: August 30, 2020

Article

Native American History in Detroit

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Detroit occupies the contemporary and ancestral homelands of three Anishinaabe nations of the Council of Three Fires: the Ojibwe, Ottawa, and Potawatomi. Through the Treaty of Detroit, the Ojibwe, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot tribes ceded the land now occupied by the city in 1807. Throughout Detroit’s history, members of these tribes have continued to contribute to the city’s development.

During the early 1900s, many Native American families moved into homes along Michigan Avenue in Detroit. Over the next few decades, Native American community leaders organized groups for social and educational activities. These groups included the North American Indian Club (later Association) in the 1940s and the Detroit Indian Educational Center in the 1970s. Both of these organizations continue to play an active role in Detroit. As of 2020, Michigan is home to twelve federally recognized tribes, with 30,000 American Indians living in the Detroit metro area.

Belle Isle

Known as Wah-na-be-zee (Swan Island) to the Chippewa and Ottawa Native American tribes, today Belle Isle reflects the late 19th century movement to create metropolitan parks begun in Paris and emulated in America by landscape architects like Frederic Law Olmsted. Originally used for fishing, hunting, and meditation, the island was involved in Pontiac’s Rebellion in 1763. The six hundred acres were later purchased by the British from Ojibwa, Chippewa, and Ottawa tribe leaders in 1769. Ownership eventually passed to American colonizers. The city of Detroit finally acquired the island, whose name had changed from Hog Island to Belle Isle in the middle of the century, in 1879.

Hull’s Trace North Huron River Corduroy Segment

During the War of 1812, British forces seized Lake Erie and its tributaries. Turning to overland supply lines, American general William Hull ordered the construction of a 200-mile road from Urbana, Ohio to Fort Detroit. Logs were placed across this ‘corduroy road’ to support wagons over the swampy terrain. Hull’s Trace is the only surviving portion of America’s first military road and first federal road. It follows the Shore Indian Trail, one of five major historic land routes out of Detroit. This route is part of the Great Trail, a network of footpaths created by Algonquin and Iroquois-speaking tribes. Hull’s Trace North Huron River Corduroy Segment is located in Brownstown Charter Township and was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.

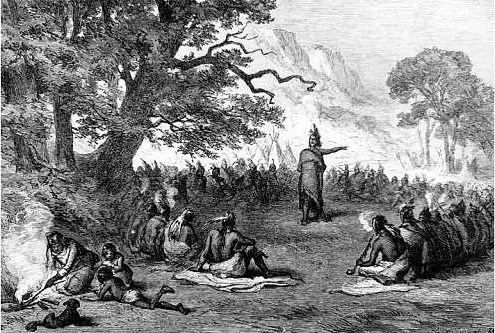

Elmwood Cemetery

The last open and visible portion of Parent's Creek runs through Elmwood Cemetery, Michigan’s oldest non-denominational cemetery. Parents Creek is the site of the Battle of Bloody Run, fought between the British and Chief Pontiac’s (Obwandiyag) coalition—factions of the Odawa, Wyandot, and Potawatomi tribes. The battle broke out on July 31, 1763 when Pontiac's forces intercepted a British attack on their encampment. Because Parents Creek ran red with blood, it became known as ‘Bloody Run.’ This battle was the peak of Pontiac’s Siege of Detroit and the fiercest battle in Pontiac’s Rebellion, which opposed land grabs by the British. Elmwood Cemetery sits within the Eastside Historic Cemetery District. The district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

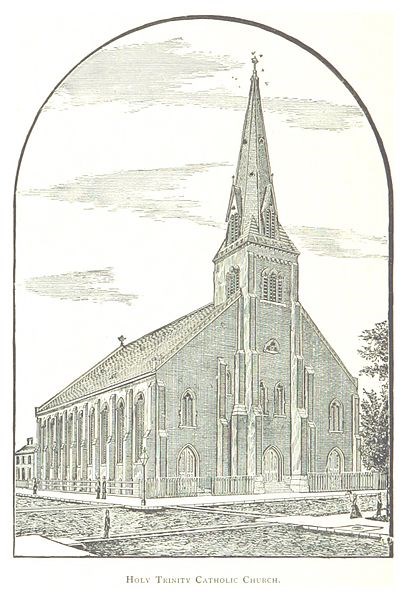

Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church

Most Holy Trinity, Detroit’s second oldest church, provided office space for the Indians of North America Foundation (INAF) during the 1970s. INAF was a branch of the North American Indian Association, which ran a food and clothing donation center and GED classes out of the church basement. INAF also aided families of Mohawk ironworkers and other Great Lakes Indians in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood. The organization offered various services to assist families that were new to the area. These services included family counseling, a health clinic, emergency food and shelter, financial help, and schooling for children from low-income families. Most Holy Trinity Catholic Church is located in Corktown Historic District. The district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1978.

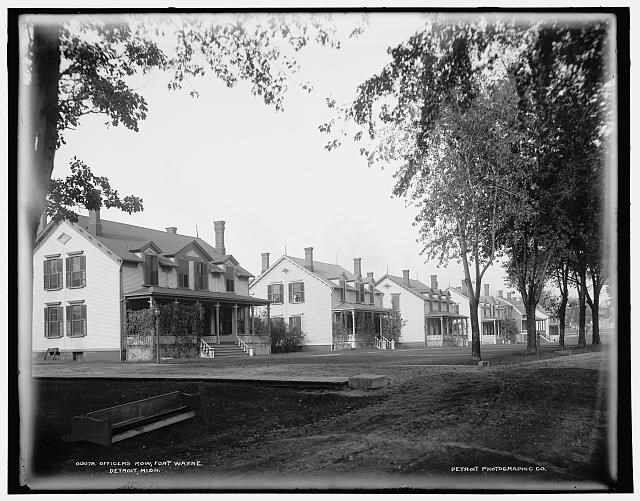

Fort Wayne

As the site of precolonial earthwork burial mounds and later a Potawatomi village, present-day Fort Wayne has held significance for several Native American tribes for over one thousand years. At the end of the War of 1812 , Fort Wayne served as the location of the Treaty of Springwells in 1815. This agreement ended wartime hostilities between the U.S. government and the Native American tribes allied with the British. By signing, the Wyandot, Delaware, Seneca, Shawnee, Miami, Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi tribes were brought under U.S. protection. To secure their allegiance, the treaty cleared the tribes of their alliances with the British and restored their prewar rights and possessions. Fort Wayne was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.

Architects Building

During the 1970s, the Architects Building housed the first official office of the North American Indian Club. Located out of Executive Director Dean George’s living room on the seventh floor, the organization originally sought to improve Native women’s access to jobs and educational opportunities. Facing discrimination in housing, employment, and public assistance, club members promoted employment and education as essential ways to advance civil rights and equal opportunity for Native Americans. As the Club grew, its purpose expanded from employment resources and social services to opportunities for Native Americans to enjoy social, recreational, and cultural activities. The Architects Building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1995.

Discover more Detroit history and culture by visiting the Detroit travel itinerary.

Selected Sources

Conway, Jim, comp. “The Site's Significance to Native Americans.” Historic Fort Wayne Coalition. Accessed July 20, 2020.

Danziger, Edmund Jeffrey, Jr. Survival and Regeneration: Detroit’s American Indian Community. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2017.

Historic Designation Advisory Board. “Final Report, Proposed Fort Wayne Historic District.” Detroit: Detroit City Council, 2016.

North American Indian Center. “History.” Accessed July 20, 2020.