Part of a series of articles titled The Struggle for Sovereignty: American Indian Activism in the Nation’s Capital, 1968-1978.

Article

Native Americans in the Poor People's Campaign

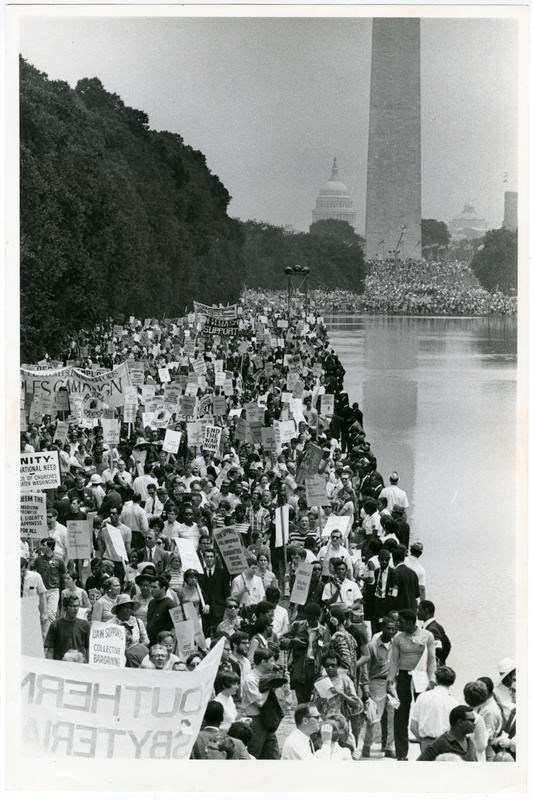

DC Public Library, People's Archive, Washington Star Photograph Collection; http://hdl.handle.net/1961/dcplislandora:571.

Introduction

On June 19, 1968, Martha Grass stood before a crowd of as many as 100,000 people assembled on the National Mall to bear witness to the poverty experienced by Native Americans across the United States.[1] A member of the Ponca tribe of Oklahoma, Grass spoke of broken treaties, which stripped Native communities of their land and tribal identities, leaving many destitute and without resources. Speaking from shared experience, this mother of 11 children connected with the many Black, white, and Chicano activists in attendance who were frustrated by the government’s lack of action in addressing the persistent problem of poverty in the United States. To enthusiastic applause, Grass challenged government representatives to come visit her in Oklahoma so they could see how poor people live. “They can come to my run-down house,” she said, adding, “I’ve got a few commodities left, and I can share with them,” referring to the federal food assistance program that was woefully insufficient.[2]

Martha Grass’s rousing speech was part of Solidarity Day, a rally and demonstration that marked the culmination of the Poor People’s Campaign. Lasting through May and June of 1968, the Poor People’s Campaign was a crusade for social justice first envisioned by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. By 1967, King had begun to argue publicly that civil rights alone would not bring about social justice. To realize the promises of American democracy, he argued, the nation would need to combat not only racial inequalities but class inequalities as well. President Lyndon B. Johnson had declared a War on Poverty in 1968, but four years later, about one-fifth of all Americans remained below the poverty line. On Indian reservations, the situation was even worse, with roughly 60 percent of Native Americans living in poverty. King envisioned an interracial coalition of poor people gathered in the nation’s capital to demand jobs and a basic income for all.

Though King was assassinated in the midst of organizing the Poor People’s Campaign, his successors in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) brought his plans to life. Participants from across the country traveled in caravans to Washington, D.C. to petition the government for specific economic and social welfare reforms through a series of marches, demonstrations, and sit-ins. According to King’s vision, they established an encampment located on the National Mall. Known as Resurrection City, the tent city served not only as a convenient rallying point for marches and demonstrations across the capital, it made the poor visible to America’s leaders by bringing the realities of economic inequality to their doorstep.

American Colonialism and Poverty in Native America

Native Americans played a significant role in shaping the objectives and message of the Poor People’s Campaign from its earliest days. In the month prior to the mass demonstration in Washington, a group known as the Committee of 100 went to Washington to bring their demands to Congress. Consisting of representatives of King’s coalition of the poor, the Committee of 100 served as the movement’s vanguard and established the agenda for the campaign to come. Among the representatives sent to Washington were at least ten activists representing Native American interests. They included Tillie Walker (Mandan-Hidatsa), who was involved with the National Indian Youth Council (NIYC), Mel Thom (Walker River Paiute), a founder of the NIYC, and Henry Lyle “Hank” Adams (Assiniboine-Sioux), who had been instrumental in the struggle for Native American fishing rights in the Pacific Northwest. The participation of Native American leaders in the Committee of 100 challenged and expanded upon the very idea of civil rights as the foundation for social and economic justice in America.

During the Poor People’s Campaign, Native peoples from reservations and cities marched arm-in-arm with African Americans, Latinos, and white Appalachians. All had been subjected to systemic inequalities in education, housing, and employment, the result of which was poverty in a land of abundance. But for Native peoples, crushing poverty was unique in that it was the result of America’s territorial expansion, broken treaties, and continuing colonialism. Instead of civil rights, as understood by the broader Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, American Indian activists demanded the right to determine their own futures as separate tribal communities and to control their own land and resources.

In a meeting with Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall and Commissioner of Indian Affairs Robert L. Bennett, Melvin Thom presented the Native American contingent’s statement on the Poor People’s Campaign. Without mincing words, the statement identified colonialism as the root cause of Native poverty and laid the blame squarely at the foot of the federal government, stating:

Our chief spokesman in the federal government, the Department of Interior, has failed us…The Interior Department began failing because it was built upon and operates under a racist, immoral, paternalistic, and colonialistic system. There is no way to improve racism, immorality, and colonialism. It can only be done away with…The Indian system is sick. Paternalism is the virus, and the Secretary of the Interior is the carrier.[3]

The statement further condemned federal management of Indian lands and resources as a cause of persistent poverty, stating, “American Indians have the political units, land bases, and are competent but we cannot use these resources because we are not allowed to control anything or to make any basic choices except to get out. That is no choice.”[4]

As Native Americans made their case before government representatives, the Native American struggle for sovereignty unfolded across the United States. Tillie Walker, who played a prominent role in organizing Native activists for the Poor People’s Campaign, had become involved in activism after experiencing firsthand the devastating impact of the damming of the Missouri River in North Dakota, which claimed more than 150,000 acres (over 90%) of her tribe’s agricultural lands and left them increasingly dependent on the federal government. In the Pacific Northwest, meanwhile, tribes around the Puget Sound were engaged in a battle with Washington state over the right to fish along the Nisqually River, a right guaranteed by the 1854 Treaty of Medicine Creek and an important means by which the Pacific Northwest tribes earned a livelihood. At the height of the Poor People’s Campaign, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of 24 members of the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes for fishing in ancestral waters with traditional gill nets in violation of Washington state law.

These and other cases demonstrated that although the Native American experience of poverty may have been similar to that of other Americans, its cause was unique. Their message was clear: addressing poverty in Native communities required no less than dismantling the colonial relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes.

Rallying the Poor

More than 200 American Indian activists participated in the Poor People’s Campaign. They traveling to Washington, D.C. in one of the many caravans of poor people that departed from cities across the nation in mid-May. After the initial Committee of 100 went to Washington to establish their agenda before Congress and the various federal agencies, participants rallied in their local communities before setting off in cars, buses, and even a mule train, all bound for Resurrection City. Throngs of people gathered in Memphis, Chicago, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Edwards, Mississippi to send off the caravans, which wound their way through cities, small towns, and rural areas, gaining participants and publicity to support the campaign.

Most of the Native American participants traveled to Washington in the Western caravan, which left from Los Angeles and San Francisco on May 15 and 16, uniting in Denver on May 18 for the remainder of the journey to Washington. A smaller caravan called the Indian Trail departed from Seattle on May 17. As they made their way to Washington, D.C., the caravans stopped at Indian reservations along the way, mobilizing support among the various tribal communities.

On May 23, the Western Caravan arrived in Washington, D.C. There, American Indian activists joined as many as 3,000 other Poor People’s Campaigners in daily demonstrations, rallies, and sit-ins at federal agencies across the city. Though most of the Native American group did not stay at the main encampment in Resurrection City, they joined their co-campaigners in protest at the Capitol, the USDA, and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. The testimony of Native American women in particular left an impression on government officials as they spoke of the challenges of feeding, housing, and clothing their children. In Washington, D.C., Native Americans came together with Black, white, and Chicano demonstrators to carry King’s message that poverty was a great social ill in America that cut across racial and ethnic lines. Even in the midst of campaign, however, there were stark reminders of the unique struggles Native Americans faced in the fight against poverty.

Native Struggles in the Spotlight

On May 27, the United States Supreme Court handed down its ruling in the case of Puyallup Tribe v. Department of Game, which stated that although the Pacific Northwest Tribes had the right to fish in traditional and accustomed places off the reservation, as guaranteed by the Treaty of Medicine Creek, the state of Washington still held the power to regulate Indian fishing practices. In effect, the contradictory ruling undermined the sovereignty of the tribes by subjecting them to the jurisdiction of the state, despite their federally recognized rights. The ruling touched off one of the most memorable events of the Poor People’s Campaign.

Among the most active organizers of the Native American contingent of the campaign was Henry Lyle “Hank” Adams. Born to an Assiniboine family on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana and raised on the Quinault Reservation in Washington state after his mother married a Quinault, Adams was politically engaged in tribal affairs from a young age. Inspired by the sit-ins of the Civil Rights Movement, Adams helped to organize fish-ins to protest state restrictions on Indian fishing rights in 1964. Four years later, when the highest court in the land handed down its decision on fishing rights, Adams was prepared to respond. Only this time, he had the coalition of the Poor People’s Campaign—and the attention of the national media—behind his efforts.

On May 29, more than 400 people from the Poor People’s Campaign demonstrated outside of the U.S. Supreme Court, in a protest of the Puyallup ruling. Chicano activists, in particular, showed up to support the lively demonstration, which included Indian chants and a delegation that included Adams, Abernathy, and a rendition of “La Cucaracha.”[5] As a result of the demonstration, a delegation of the protesters, led by Adams, gained an audience with Chief Clerk John Davis, whom they presented with a statement of protest. Although much of the press covering the event was negative—focusing on a few broken windows and the circus-like atmosphere that pervaded much of the protest—for many of the protesters, the demonstration was a victory because it brought Native concerns to the center of political discussion, when it was normally ignored altogether.[6]

Being in Washington, D.C. brought American Indian activists to the doorstep of the agency that had so much power over their lives—the Bureau of Indian Affairs, an agency within the Department of the Interior. In faraway reservations and urban Indian enclaves, government officials in the BIA and the Interior seemed far removed from the struggles of Native Americans. In the Poor People’s Campaign, American Indians seized the opportunity to bring their issues directly to Department officials, often with a theatrical flair that could not be ignored.

Two days after the dramatic demonstration at the Supreme Court, a coalition of 60 Native American demonstrators surprised the Indian Claims Commission at the BIA to demand better and more just compensation for land taken from Indians in the past century. To illustrate the point that Indians had received inadequate compensation for the lands taken from them, Frank Allen of the Stillaguamish tribe attempted to purchase an acre of land from any member of the commission at the price of $1.10—the same price the government had offered his tribe per acre of land. Reportedly, there were no takers.[7] In the coming weeks, Native activists took center stage at sit-ins and demonstrations at the Supreme Court, the BIA, and the Departments of Interior and Agriculture, reiterating the demands they had made during Committee of 100’s initial visit to the capital and protesting the recent Puyallup ruling.[8]

The campaign reached its apogee with the Solidarity Day on June 19, when Martha Grass spoke to the thousands assembled before the Lincoln Memorial. After this, the campaign unraveled quickly. Resurrection City’s permit, which had already been extended once, was set to expire at 8:00 p.m. on June 23. When the National Park Service declined a second extension of the permit, George Crow Flies High (Hidatsa) presented Ralph Abernathy with a “Proclamation of Temporary Cession, signed by members of the Native contingent, which stated that the federal government had illegally expropriated the land, and that Native peoples were now reasserting their rightful claim to it, and granting permission to the Poor People’s Campaign to continue using it.[9] This final, symbolic claim to the land, of course, would not be recognized by federal authorities, and just after 11:00 a.m. on June 24, authorities began to clear the encampment. The remaining protesters lined up peacefully to be arrested, roughly 230 in all. The Poor People’s Campaign had come to an end.

The Poor People’s Campaign: Only the Beginning

On the surface, it would seem that the Poor People’s Campaign had not been a great success. Falling far short of the sweeping reforms the organizers had originally envisioned, seven weeks of protest had resulted only in a modest expansion in food stamps and child nutrition assistance and had not achieved any of the major legislative objectives. Congress had also failed to act on the issues specific to Native Americans. The Poor People’s Campaign remains a largely forgotten chapter in history of the Civil Rights Movement. But for many Native Americans involved in the Poor People’s Campaign, the dismantling of Resurrection City did not mark the end of a campaign so much as the beginning of a new era in American Indian activism.

Even as Native activists built solidarity with non-Native activists, the Poor People’s Campaign highlighted some of the key differences in their struggles. Most importantly, the American Indian struggle was the struggle of colonized peoples demanding sovereignty, rather than simply an extension of the movement for civil rights. Frustrated with their appointed representatives in the federal government, Indian activists would increasingly engage in direct action to assert their sovereignty and reverse the devastating policy of termination.

In the weeks following the Poor People’s campaign, native activists in Minnesota founded the American Indian Movement (AIM). The following year, a group that called itself the Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz island. These two events would coalesce in the next major Native American demonstration in Washington, D.C. But this time, Native politics would take center stage in the Trail of Broken Treaties.

[1] Estimates vary widely, putting the crowd size anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000. Gordon K. Mantler, Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition & the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2013), 173.

[2] “Ponca Indian Attacks ‘Rich’ in D.C. Talk,” Daily Oklahoman, 20 January 1968; “CR only one issue with minorities,” Pocono Record, 21 June 1968.

[3] “Statement of Demands for Rights of the Poor Presented to Agencies of the U.S. Government by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and Its Committee of 100, 29-30 April and 1 May 1968,” as quoted in Say We Are Nations: Documents of Politics and Protest in Indigenous America since 1887, ed. Daniel Cobb (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 149-150.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Mantler, Power to the Poor, 164.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jim Hoagland, "Fair's Fair—Indian Offers $1 an Acre for LBJ Ranch," Washington Post, 1 June 1968.

[8] Daniel M. Cobb, Native Activism in the Cold War: The Struggle for Sovereignty (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2008), 186-189.

[9] Cobb, Native Activism in the Cold War, 189.

Last updated: June 26, 2024