Last updated: January 9, 2024

Article

Nagamowin Akiing: Bineshiiyag Gichi Onigamiing (The Singing Land: Birds at Grand Portage)

NPS photo

Annual songbird surveys at Grand Portage provide a glimpse into population changes over time. Many of the songbirds nesting here in the summer migrate south in the winter, some as far as South America. So birds face challenges across a broad swath of space and time. It is up to us to protect the northern forest so there continues to be good breeding habitat for our winged neighbors.

2014–2018

In a recent analysis of data collected from 2014 through 2018, we found the Ovenbird and Nashville Warbler had the densest populations at Grand Portage, with each averaging 71 birds/mi2. Blackburnian Warbler was the least dense species, averaging 24 birds/mi2.Among seven species with increasing trends over the five-year period, Nashville Warbler and American Redstart were the only two whose increases were stastically significant, rising by 16 birds/mi2/year and 8 birds/mi2/year, respectively. Red-breasted Nuthatch was the only species to show a declining, but non-significant, trend.

© D. Blecha/Macaulay Library-CLO/NPS collection; WikimediaCommons/W.H. Majoros; NPS photo

Three guilds (a group of species that share a common trait such as habitat type, nest location, or food source) showed significant increasing trends in 2014–2018: insectivores such as warblers and vireos (+6 birds/mi2/year), aerial foragers such as the American Redstart (+7 birds/mi2/year), and woodland species (+5 birds/mi2/year). Permanent resident species exhibited a declining, but non-significant, trend.

Photos: NPS/G.Etter, NPS/R.Hannawacker, NPS/K.Miller, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, USFWS/S. Maslowski, N.Dubrow/Macaulay Library-CLO/NPS collection, D.Jauvin/Macaulay Library-CLO/NPS collection, NPS/T.Wilson.

The Future of Bird Song at Grand Portage

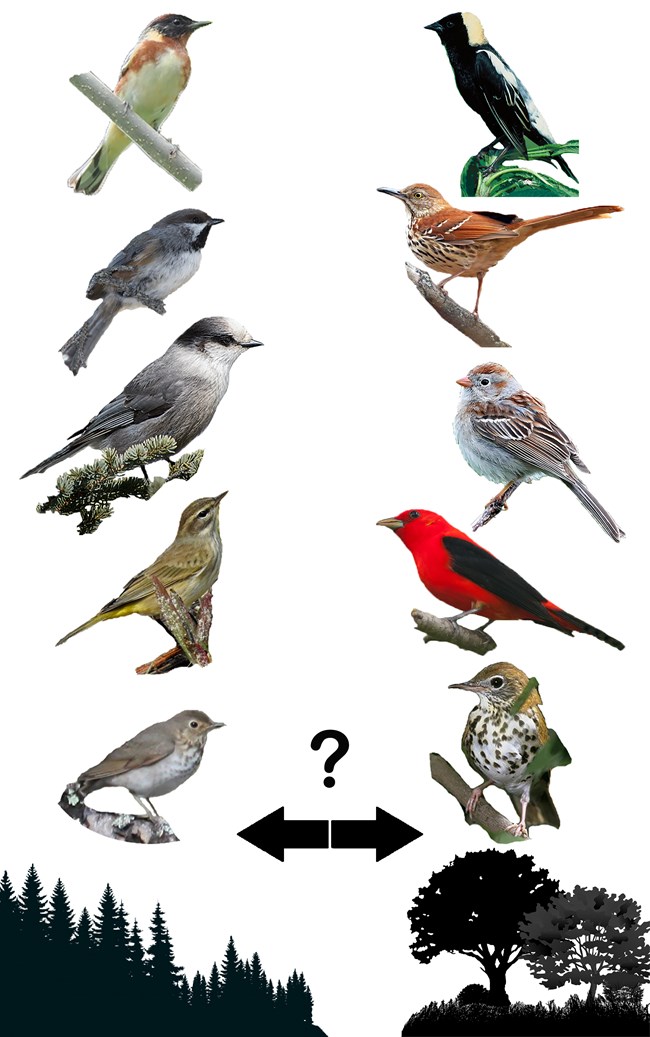

One study comparing bird population changes under two different climate scenarios (high and low greenhouse gas concentration trajectories) predicted high turnover of species populations at Grand Portage by mid-century (2041–2070) if the nation continues on its current path of rising emissions1. Forest species such as the Least Flycatcher and Mourning Warbler are among those whose populations are predicted to decline under both climate scenarios, while iconic northern species such as Bay-breasted Warbler, Boreal Chickadee, Gray Jay, Palm Warbler, and Swainson’s Thrush are predicted to disappear from the Grand Portage area under both scenarios.Some species already found here, and a few that are not, are predicted to improve under both scenarios, including the Baltimore Oriole, Bobolink, Chipping Sparrow, Eastern Kingbird, Eastern Phoebe, Savannah Sparrow, Song Sparrow, Warbling Vireo, and Yellow Warbler.

Other species more common in hardwood forests and grasslands to the south will benefit from the warming climate and expand their range to the Grand Portage area. They include the Barn Swallow, Brown Thrasher, Eastern Meadowlark, Field Sparrow, Great Crested Flycatcher, Indigo Bunting, Ring-necked Pheasant, Scarlet Tanager, Willow Flycatcher, Wood Thrush, and Yellow-throated Vireo.

These changes are only predictions, not certainties. But as climate changes continue to take shape, these predictions create a vision of a much different bird community at Grand Portage. Is that important? They are different species, but they are still bineshiiyag. The northern species have not gone extinct, they have only shifted further north. The songs may have changed, but the land is still singing. Still, the place known as Gichi Onigamiing could change in a way that even the Anishinaabe who have been here for generations may not recognize.