Part of a series of articles titled The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 25, No. 1, Summer 2025.

Article

My Time with Great Basin National Park Resource Management

This article was originally published in The Midden – Great Basin National Park: Vol. 25, No. 1, Summer 2025.

Caitlin Kouba

While checking National Parks off my bucket list as a tourist, Great Basin National Park (GRBA) initially did not impress me. I mostly remember repeatedly driving back and forth from Ely, not seeing the night sky, trudging through icy rain, and bribing my daughter to go on a cave tour. Years later, when I applied for and was hired to be an interpretive ranger, I saw it as my foot in the door of the National Park Service; a stepping stone to learn and grow before moving on to a new park the following season. Little did I know that Great Basin National Park choosing me would be one of the best things to ever happen to me.

For nine months as a seasonal interpretive ranger, I was challenged mentally and physically, shoved out of all my comfort zones, and broke multiple pairs of glasses. While I faced these challenges on my own, I was never alone. A new kind of family had taken me in: my GRBA family. We weathered storms, laughed, cried, and celebrated every chance we had. When it came time to leave at the end of my season, I was heartbroken, not only to leave the wonders of GRBA but the people I had come to love.

I was able to return sooner than expected as a volunteer with Resource Management at GRBA. After my brief time volunteering, I believe that time in resources should be a training requirement for interpretive rangers. Sharing the dorms with interns of the resources team and hearing about their research and the work that goes into it did not prepare me for the vast opportunities and responsibilities I have been encouraged to explore in my time here.

I spent time with Resource Program Manager Bryan Hamilton, who had a project repairing the park's landscape damaged by the water line replacement. With a small army of GRBA administration, resources, and The Great Basin National Park Foundation employees, 20 acres were seeded with a mixture of sagebrush, wildflowers, and grasses. The vast support from the entire park allowed this project to be completed in less than a day instead of the two days planned initially; a side project even formed cleaning up trash and construction debris before we began raking the seeds into the soil.

NPS/Bryan Hamilton

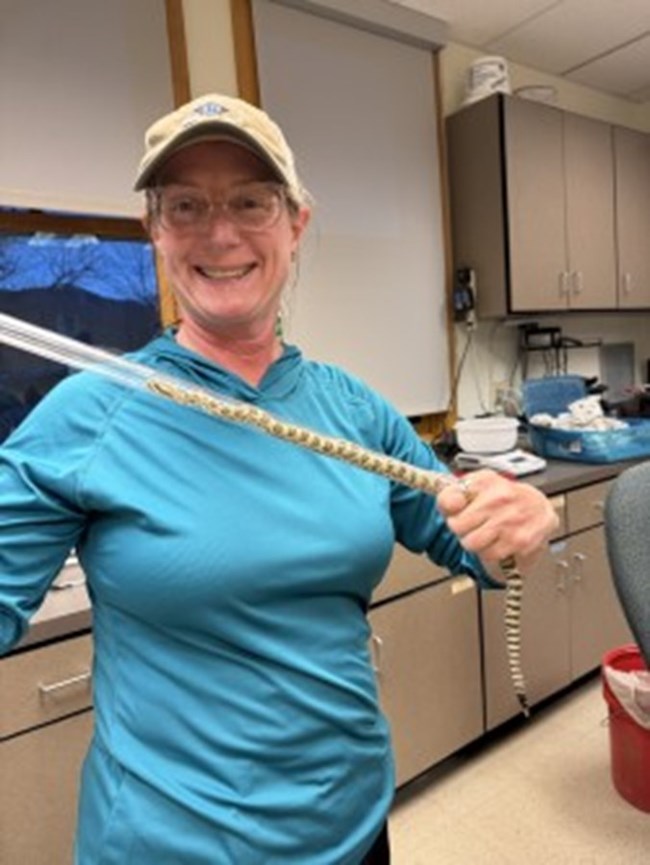

Later, I was invited to gather, collect, and, to my surprise, release the rattlesnakes. It was surprising because I didn't know the bucket I was carrying had two live snakes inside until I fell, and Cameron took them away from me "for the snakes." As an exotic animal keeper, I have never enjoyed working with snakes. It was not until Bryan showed me proper handling and data collection techniques that I no longer feared but respected these fantastic animals. I cannot wait for my next opportunity to assist with this research project and share my experiences with visitors.

Jake Schas

GRBA is also part of the Mojave Desert Network (MOJN) Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) selected large springs protocol. The purpose of NPS I&M is to track vital signs, such as water resources, with critical human values or resource significance. Marmot Springs is measured quarterly, while two other springs are measured when accessible. These springs were chosen because there is no evidence of human manipulation. GRBA's role is to time how fast a known volume container fills with water and report the findings.

Two other volunteers and I assisted Jon with relocating invasive fish from Snake Creek. We worked slowly upstream from the park border to a concrete barrier while electrofishing and collecting all the stunned fish. We aimed to prevent the invasive fish from being reintroduced to the park and endangering our Bonneville Cutthroat Trout population. The trout were moved further downstream, away from the park boundary, for anglers of all types to enjoy.

Olivia Ford

While Lehman Caves has been harmed repeatedly throughout its human history, you can repair some damage if you are patient and good with puzzles. Kirsten Bahr, Physical Science Technician with Timpanogos Cave National Monument, demonstrated how to repair formations. Afterward, she supervised as those present glued pieces back together. For little formations, simply gluing and time will work. The glue used is an epoxy with a low heat index and is non-toxic. Pins, mortar mix, and supportive tools are required along with time for larger formations.

Finally, with Gretchen's and Kirsten's encouragement, I have started what I hope becomes a long-term microclimate study of Lehman Caves. While it is not difficult, it is time-consuming as there are 24 different locations along the tour path. There are several purposes of this study. The first is to monitor how much people influence carbon dioxide (CO2) levels, humidity, and temperature. The second purpose is determining when condensation corrosion may occur in the cave. Condensation corrosion causes the gradual disappearance of cave bedrock and formations. Higher CO2 levels also will reduce the ability for calcite accruement. Lastly, we want to compare the current lighting system with the incoming system. The current lighting system was installed in 1977 and is scheduled to be replaced in late 2025. Monitoring these items can help determine if the installation process and improvements to the lighting system are helpful or harmful to the cave ecosystem.

While my time with GRBA Resource Management has officially ended, I plan to continue assisting this fantastic group of individuals and the projects they are so passionate about. I also plan to share the knowledge I have been graciously gifted with GRBA's visitors. I hope to inspire our visitors to learn more about this special park, just as the resources staff have inspired me.

Last updated: May 14, 2025