Last updated: October 30, 2020

Article

Murder, Mayhem, Voter Fraud, and Political High Jinks: The U.S. Army’s Thankless Task in the South, 1865-77

Wikipedia

With the Union victory over the Confederate movement in 1865, the federal army was given the task of assisting in the readmission of the southern states into the body politic, and in protecting the newly awarded political and civil rights of the freedmen.

It was a tall order for an army increasingly short of manpower. The calls for economy within the halls of Congress, in the months after Lee’s surrender, led to a reduction of the Army (volunteers and regulars) from a high of over 1.5 million to 54,000 by the end of 1866 – with more reductions to come. (The U. S. Navy fell under a similar axe.)

Approximately one-third of that much smaller force – 18,000-20,000 – was stationed in the former Confederacy, an area the size of Western Europe with a population of eight million people. It was in effect, an occupation force, a role largely unfamiliar to it.

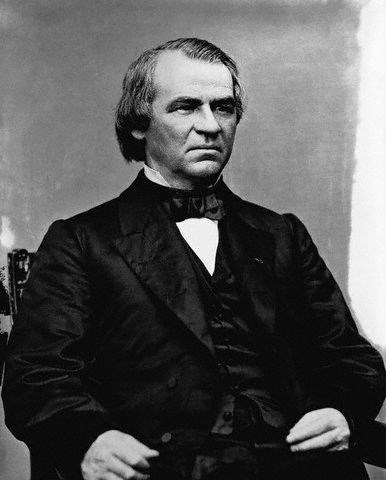

Library of Congress

Over the twelve years of the Reconstruction era, the Army executed the political will of successively, President Andrew Johnson, the Radical Republicans in Congress, and finally Presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Rutherford B. Hayes.

On May 29, 1865, President Johnson issued two proclamations. One established a loyalty oath to be taken by Southerners, foreswearing any previous allegiance to the Confederacy. The second proclamation made William Holden the provisional governor for the state of North Carolina. Later, other provisional governors were appointed in the South.

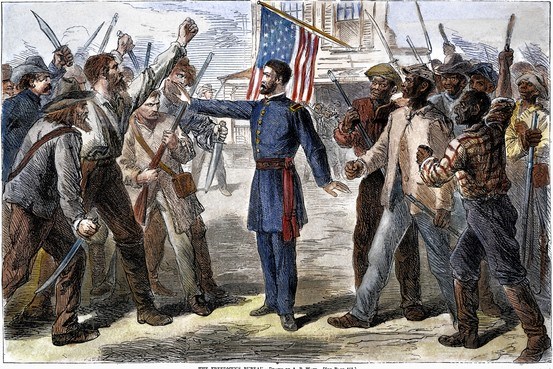

The Army was tasked with aiding the process of readmission for the Southern states by overseeing elections for the calling of state conventions to ratify the 15th amendment to the Constitution, abolishing slavery and pledging loyalty to the Union. The Army also had the duty of protecting freedmen and their white, Republican supporters, aiding the Freedmen’s Bureau, preventing violence, and helping to reestablish civil authority.

One of the problems that the Army faced was the continued resistance of native white Southerners to “domination” by the North. There was also resentment of the presence of black troops. Many were eventually removed in the effort to keep peace.

HarpWeek

President Johnson’s loyalty oath was problematic. Too many Southerners were disqualified for public office because they could not affirm that they had not come to the political, economic, or military aid of the Confederacy during the war years. Therefore, too few native-born Southerners were available to reestablish civil government. Complicating matters even more, many of those who took the oath were later determined to be disloyal after all, and were removed by Army commanders. These actions created tensions between the Army and the civilian leaders with whom it hoped to cooperate.

Many Army commanders desired to have civil leaders assume responsibility for preventing violence and other criminal acts, rather than having their troops intervening. Army commanders occasionally refused to come to the assistance of civilian leaders, adding to confusion and tension within Southern communities. Meanwhile, Radical Republicans, unhappy with Andrew Johnson’s “lenient” reconstruction policy, wrested control of Reconstruction from the President in 1866 and 1867.

Congressional Republicans established a Joint Committee on Reconstruction to investigate conditions in the South and to propose measures to prevent violence and disorder. The result was the passage of two Reconstruction acts in March 1867. These acts placed the South under military control, and created five military districts with commanders who were given sweeping powers to protect persons and property (meaning blacks and their white Republican supporters), remove disloyal civil officials, and replace civil courts with military commissions when deemed necessary. The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 also declared all Southern state governments to be provisional and prohibited the formation of independent militias (most of which were white).

Biography.com

The Radical Republicans wanted to punish Southerners for the war, and they wanted the Army to occupy and control the political situation in the former Confederacy. As such, commanders were very aware of the need to insure that their troops conducted themselves in ways that did not make the Southern white population needlessly hostile. It was an almost impossible task. Not only did some Union commanders and their troops have an automatically negative view of “former rebels,” but those “former rebels” returned the compliment.

From 1867 to 1870, incidents of violence in the South were sporadic, though frequent enough. Peace was often tenuous as blacks and white Republicans continued to be under threat and white Southerners continued to feel imposed upon by a vindictive federal Congress.

Matters only got worse after 1870. All the former Confederate states had by this time ratified the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments abolishing slavery, granting citizenship, and the vote. They were thus readmitted to the Union. Though President Grant pleaded, “Let us have peace,” was president, it was not to be.

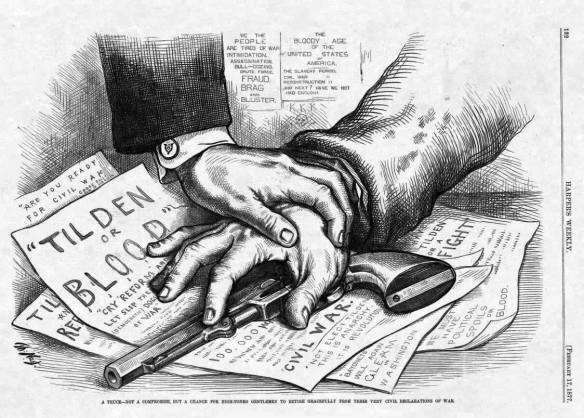

Harper’s Weekly

Fraud at the ballot box became more common once the Democrats regained political power in the mid-1870s in several states. As South Carolina’s “Pitchfork Ben” Tilden bragged, “How did we recover our liberty [after the ballot box had been given to “our own ex-slaves”]? By fraud and violence.” After the polls closed, ballot boxes were seized. Votes were “counted in” or “counted out,” as need be. Gerrymandering was practiced to reduce Republican voting strength. One black Congressional district in Mississippi was concentrated in a narrow band along the Mississippi River to insure white majorities in five others. Mob attacks and lynching were also employed to discourage black and white Republican voting.

“White Leaguers,” the “White Liners,” the “Red Liners,” and the “Red Shirts” came into being, bent on terrorizing black citizens and white Republicans. The Ku Klux Klan also formed at this time. Violent outbreaks in the streets and at the polls were so frequent that at times, the army was called on to literally form a barrier in public spaces between warring Democrats and Republicans. In Louisiana in 1872/1873 Republicans took possession of the state house and Democrats took possession of a nearby hall. The Democrats attempted to overawe the Republicans with an attack of “militia.” The Army sent troops to regain control over a situation that promised increasing violence.

In the 1876 November elections in Louisiana and South Carolina, a familiar scenario played out: Democrats and Republicans in both states claimed victory, not only in the presidential election, but in the elections for governor and state legislature, too. Each side backed up its claim through the threat of mob violence. By this time, President Grant had already voiced his concern that, “The whole public are [sic] tired out with these annual autumnal outbreaks in the South and… the great majority are ready now to condemn any interference on the part of the [federal] government.”

Indeed, by the end of 1876 there were fewer federal troops to protect persons and property in the South than at any point since the end of the war. Those overextended troops could no longer effectively monitor elections in that region. Reconciliation between the North and South remained elusive, despite the hopes of men of good will.

The final withdrawal of federal troops from South Carolina and Louisiana to their barracks was a concession to the reality that military force to protect persons and property in the South had failed to bring about the social justice that the victors in the late war had sought.

Written by Alan Gephardt, Park Ranger, James A. Garfield National Historic Site, August 2017 for the Garfield Observer.