Last updated: January 16, 2023

Article

The Mud March

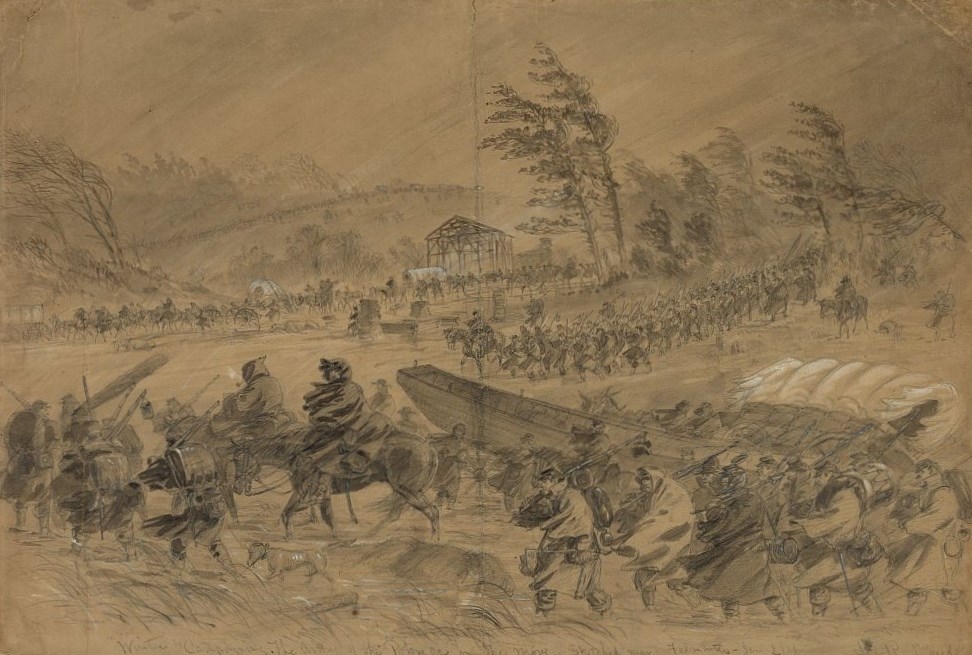

Alfred Waud, Library of Congress

Despite disaster at Fredericksburg, US Army of the Potomac Commander Ambrose Burnside watched for an opportunity to reverse his fate into January. He found a glimmer of hope: in addition to the unseasonably warm weather, reports indicated that Federal actions in the Carolinas had forced Lee to send some of his army south. These circumstances seemed to offer the opportunity to strike at Lee. On January 20, 1863, the Army of the Potomac was on the move again.

The plan was simple: a lightning-fast dash to the west of Fredericksburg, where Burnside hoped to cross the Rappahannock River at Banks’ Ford placing his army directly in Lee's rear. Additional troops would provide a decoy at the same river crossings across from Fredericksburg the Army of the Potomac had used one month before.

As the sun set on January 20, all had gone according to plan. The army had moved into place swiftly, and the morale of the rank and file lifted. Lee had not yet shifted his forces, and Burnside estimated that the quick march had put the Army of the Potomac 48 hours ahead of the Confederates. Around 7 pm that evening, however, it began to rain with a force that increased every hour.

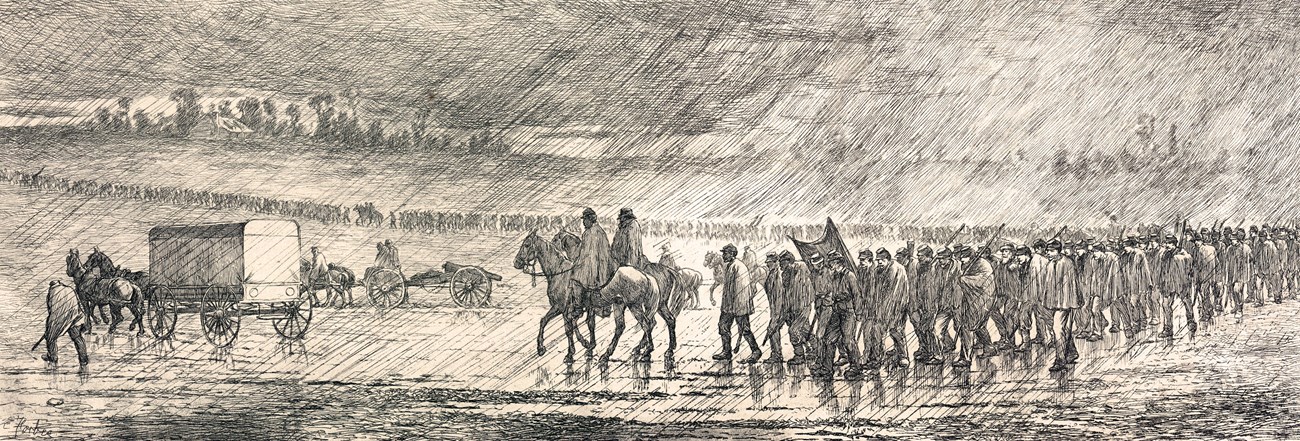

Edwin Forbes, Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University

The rain continued all night and into the morning of January 21. Federal camps and roads turned to mud pits overnight. The poor condition of the roads caused delays and officers scrambled to figure out a way to continue the operation. The following letter from General Daniel Woodbury from his position at Banks’ Ford to General Burnside indicates an increasing concern about the campaign:

HEADQUARTERS ENGINEER BRIGADE,

Near Banks' Ford, January 21, 1863.Major-General BURNSIDE,

Commanding Army of the Potomac:

Since seeing you, I have looked over into the enemy's country, and cannot positively make out any signs of re-enforcements; still, there can be no doubt as to the enemy's knowledge of our location and intentions. Our camp-fires last night presented to Lieutenant Cassin, aide-decamp, 3 miles from this place, the appearance of a large sea of fire. Our smoke to-day covers the country, and reaches far beyond the opposite banks. Before the rain began, we had every prospect of being able to throw three bridges over at daylight. The rain has prevented surprise, and changed our condition entirely.

It seems to me the part of prudence to abandon the present effort, not only because the enemy must be aware of our intention, but because the roads are everywhere impassable. As the enemy, doubtless, has some guns in position on the opposite side, he will not be so dependent upon the condition of the road; besides, he has a plank road coming up to the probable field of battle. All my men are tired out by their night work, and cannot give to the fatigue parties that energetic attention necessary to efficiency. We can, I have no doubt, be ready to build our bridges at daylight to-morrow morning; hardly before. We could build two this afternoon, but if we could build a dozen this afternoon, I think it would be better to abandon the enterprise.Respectfully,

D. P. WOODBURY,

Brigadier-General of Volunteers.1

Despite the weariness of the troops, the Army of the Potomac was, at least in theory, within striking distance of the river crossing. Burnside, obstinate, ordered the army to march on even as the rain continued to fall in sheets upon his men. The march proved to be beyond miserable. The flow of men, animals, and wagons turned roads into soup. Regiments were forced to stop and rest every 100 yards just from the effort of walking through the mud. Wagons and cannon sank to their axles and were abandoned as not even the efforts of a dozen horses could move them.

As the miserable day came to an end, a poor omen appeared on the banks of the Rappahannock opposite the site Burnside had planned to cross: campfires of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

On the morning of January 22 it became clear that Burnside had again lost a race to Robert E. Lee. Confederates yelled jeers and insults across the river at the miserable US troops. The campaign was over. The Mud March, as this infamous movement would become known, was not.

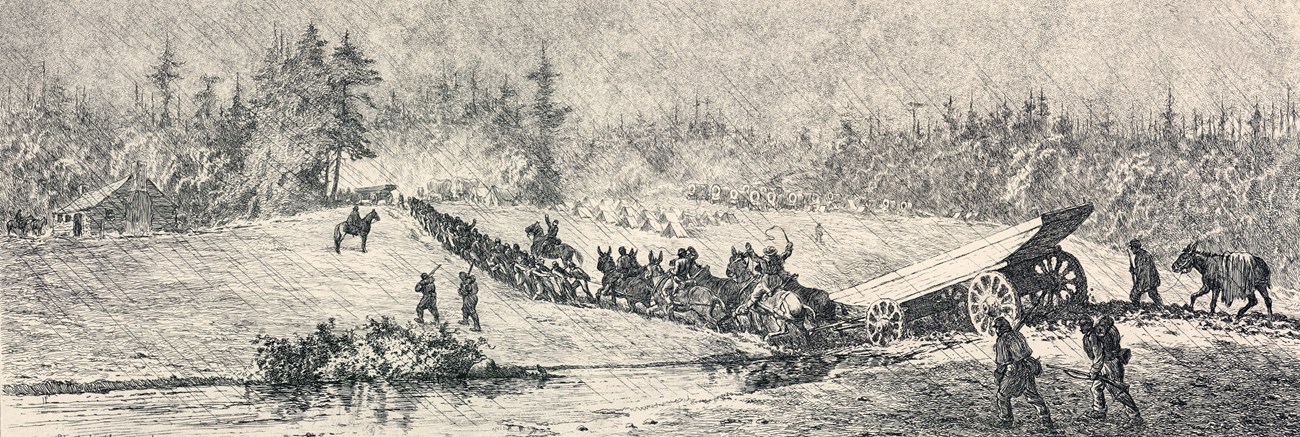

Edwin Forbes, Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University

War correspondent William Swinton wrote of the deteriorating conditions the army faced:

The ground had gone from bad to worse, and now showed such a spectacle as might be presented by the elemental wrecks of another Deluge. An indescribable chaos of pontoons, vehicles, and artillery encumbered all the roads-supply wagons upset by the road-side, guns stalled in the mud, ammunition-trains mired by the way, and hundreds of horses and mules buried in the liquid muck. The army, in fact, was embargoed: it was no longer a question of how to go forward-it was a question of how to get back.2

Burnside ordered the army to return to their original camps on January 22. The retreat began on the 23rd. Fortunately for the Federal troopers, the rain slowed significantly. Unfortunately, they had to return using the same roads they had destroyed during their advance. It would take some men until the 26 before they made it to their original camps on Stafford Heights.

Exhausted, the Army of the Potomac hit rock bottom after the Mud March. So, too, did its commander, Ambrose Burnside.